CHAPTER

XIV.

CRETACEOUS

SERIES.

WHEN the

continent described in last chapter had endured for a long period of

time, submergence

of the area began to take place, accompanied by the deposition of the

purely marine CRETACEOUS

SERIES, which in England is as follows, the oldest beds being placed at

the

bottom:

I may here

mention that in parts of the Continent of Europe, there are certain marine

formations intermediate in position and date between the Oolitic and

Cretaceous rocks, which

are known as the Neocomian beds, so called from Neocomium, the ancient

name of Neuchâtel, in

Switzerland, where they are well developed. The assumption that the

Hastings Sands and Weald

Clay are the fresh-water equivalents in time of the lower and middle

parts of these continental

beds, is undoubtedly correct, the Lower Greensand of English geologists

being the British

representative of the Upper Neocomian strata.

Mr. Judd has shown that at the south end of Filey

[Atherfield Clay. 213]

Bay, in Yorkshire, we have the actual marine representatives of the

continental Neocomian

strata. These Yorkshire beds were formerly called Speeton Clay, and lie

between the uppermost

Oolitic strata of the district, called by Mr. Judd, Portlandian, and

the Red Chalk or Hunstanton

Limestone, which, according to that author, cannot be of later age than

the Upper Greensand, and

may he as early as the Gault.1

The area occupied by the Purbeck and Wealden strata underwent a long

period of slow

depression, during which these fresh-water strata with occasional

marine interstratifications

were deposited; and by sinking still further, the purely marine beds of

the Atherfield Clay

began to be formed. In fact, but for the presence in it of marine

fossils, it is hard to draw any

line between the Wealden and the Atherfield Clays, and no doubt the mud

that formed the latter

was at first carried seaward by the same great river, in the manner,

for example, that muddy

sediments are now deposited at and near the mouth of the Amazons on the

east coast of South

America.

The Atherfield Clay takes its name from Atherfield, on the

south-west coast of the Isle of Wight,

where it is well seen overlying the Weald Clay, and is overlaid by the Lower

Greensand. Its

lowest beds form a kind of passage from the fresh-water strata of the

Weald into the overlying

marine beds of the Lower Greensand, both in the Isle of Wight and in

the Wealden district, round

which it circles at the edge of the Lower Greensand; for at Atherfield

there seems to have been a

depression of the fresh-water area and an influx of the sea,

accompanied by the appearance of

Cerithium carbonarium, accompanied by Pinna and Panopœa

standing vertically in the

position in which they lived. Many other shells

1

'Journal of the Geological Society,' 1868, vol. xxiv., p. 218.

[214 Lower Greensand.]

are scattered through the clay, including the well-known Perna Mulleti, Trigonia

caudata, Gervillia aviculoides, Areas, Pectens, Oysters,

Rostellaria Parkinsoni, and Hemicardium Austeni, &c.

&c.

THE LOWER GREENSAND, of which the Atherfield Clay is a subdivision,

comes next in

succession, in the Isle of Wight, beginning with a bed of sandstone

containing Gryphœa sinuata

and many other shells, succeeded by 29 feet of clay, vulgarly called

the 'lobster bed,' from the

presence of Meyeria magna, formerly called Astacus,

together with Ammonites Deshayesii, &c.,

overlaid by nodular bands with Gervillia aviculoides, &c..,

above which, clay is repeated, with

the same Meyeria. Above this, sands and clays alternate to the top of

the series, with many

fossils, among which may be mentioned as characteristic, Terebratula

sella, T. Gibbsii, T.

biplicata, Limas, Gryphœas, Gervillia solenoides,

Ammonites, Nautili, and other remarkable

Cephalopoda of the genera Crioceras, Ancyloceras, and Hamites.

The whole of these strata

overlying the Wealden beds occur in magnificent sections along the

southern cliffs of the Isle of

Wight, dipping northerly under the Gault, Upper Greensand, and Chalk,

which in a high ridge

stretches across the island from Culver Cliff to Alum Bay. Overlaid by

the Gault, and reposing

on the Weald Clay, the Lower Greensand also sweeps round the whole

Wealden area from

Sandgate to Guildford and Haslemere, and from thence to the coast north

of Beachy Head. Between

Guildford and Haslemere it forms high scarped terraces. The sands are

sometimes quite soft,

with intercalated hard bands, and they are frequently ferruginous. A

good building stone, very

fossiliferous, being sometimes an impure limestone, called the Kentish

rag, lies in the lower

part

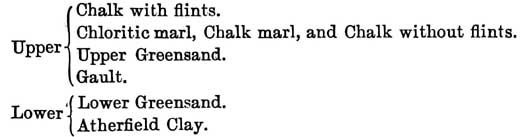

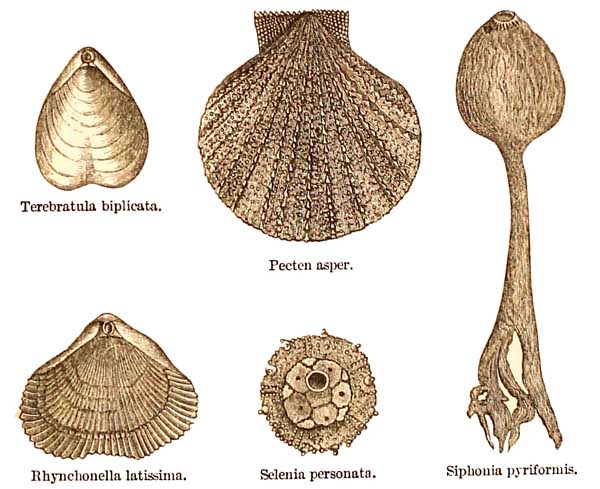

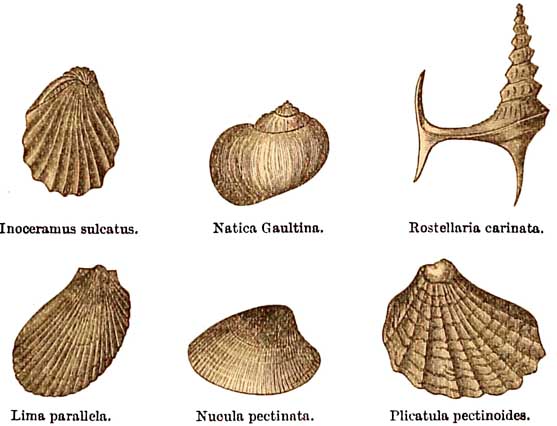

FIG.

42.

Group of Atherfield Clay and Lower Greensand Fossils.

[216

Lower Greensand.]

of the formation, on the north side of the Weald at Maidstone. It rests

on the Atherfield Clay. The

general grouping of the fossils in all this area correspon is with that

of the Isle of Wight. In

Dorsetshire and part of Somersetshire, at the south end of the western

escarpments of the

Cretaceous rocks, the Lower Greensand is absent, and the Upper

Greensand rests directly on the

Lias and New Bed series. Further north, the Lower Green sand reappears

in Wiltshire, near

Chapmanslade, about three miles east of Frome, and in a long narrow

band follows the direction

of the escarpment of Chalk, as far as the neighbourhood of Devizes,

where it widens for a space,

and runs north in a projecting tongue as far as Farringdon, where it is

known as the Sponge

gravel.

Beyond the Farringdon area, it is for a space of twelve miles

overlapped unconformably by the

Gault, to reappear a little south of Abingdon in a broad patch, that

extends eastward about six

miles to Chiselhampton, where it is again overlapped by the Gault, to

reappear in a narrow

strip between Great Hazeley and the neighbourhood of Thame. Several

small outliers of Lower

Greensand lie on the Purbeck strata, south, west, and north of

Aylesbury. At Leighton Buzzard

it appears in great force, covering all the country for miles round

Woburn, from whence it

trends away to the north-east, and disappears under the alluvium of the

Fens of

Cambridgeshire, and runs along the east side of the Wash, where,

crossing under sea, it

reappears in Lincolnshire, and following the line of the chalk

escarpment runs in a NNW. line

to the Humber. As a whole this formation may be described as consisting

of yellow, grey, white,

and green sands.

In the Weald country and on the north-west

[Lower Greensand. 217]

side of the great Chalk escarpment, between Devizes and the Wash, the

Lower Greensand is

often ferruginous, and has been worked for iron ore both in ancient and

modern times. Fossil

wood is of frequent occurrence, perhaps of Coniferous trees, and all

the evidence tends to show

that, in the English area, the strata were deposited in comparatively

shallow seas not far from

shore.

The general characters of the fossils of the series are

as follows:—Echinoderms of the genera Salenia, Cardiaster, Diadema, Discoidea,

Echinobrissus, together with Pentacrinites, are found in

it.

Terebratulœ and Rhynchonellœ are of frequent occurrence,

with a few other Brachiopoda.

Among the Lamellibranchiate molluscs are numerous Limas,

Gervillias, Perna, Oysters,

Pectens, and Pinnas, together with shells of the genera Cardium,

Venus, Trigonia, Myacites,

and Nucula. Gasteropoda are not generally numerous. Cephalopoda

of remarkable forms are

characteristic; for, in addition to several species of Ammonites,

Nautili, and Belemnites, there

are Crioceras, and Ancyloceras, like Ammonites half

unrolled, Crioceras Bowerbankii,

Ancyloceras gigas, A. grande, and A. Hillsii. Fishes are

scarce, and only three reptiles have

hitherto been described, one Chelonian, Protemys serrata, a Plesiosaurus,

and a crocodilian

saurian Polyptychodon continuus, said also to occur in the

Lower Chalk.

Out of about 300 Lower Greensand species, 18 or 20 per cent. pass into

the Upper Cretaceous

series. Partly for palæontological considerations, and also

because the Gault seems sometimes to

lie, as it were, unconformably on the eroded surface of the sand, the

dissimilarity in the

grouping of fossils is so great, that

[218 Gault.]

it has been considered advisable to draw a marked line between the two

groups; the Atherfield

Clay and the Lower Greensand, when the term Neocomian is not applied to

them, meaning Lower

Cretaceous, and all above them to the topmost beds of the Chalk

being considered as Upper

Cretaceous strata.

The GAULT forms the base of the Upper Cretaceous

series—or of the Cretaceous series, for those who choose to call the

Lower Greensand Neocomian.

It is a stiff blue clay, about 300 feet thick in its thickest

development, but sometimes it is hard

to separate it lithologically from the Upper Greensand. It appears in

the Isle of Wight, overlying

the Lower Greensand all across the Island; and ranges round the

escarpment of the Weald in the

same position, with occasional signs of a kind of unconformable erosion

between them; and in

the centre of England, from the neighbourhood of Devizes to the Wash in

Norfolk, the Gault

occasionally completely overlaps the Lower Green sand in an

unconformable manner. In proof of

this unconformity, occasional outlying patches of the Lower Greensand

occur north of the Chalk

escarpment, without any visible signs of it immediately at the base of

the neighbouring Upper

Cretaceous strata, which there ought to be, if these formations lay

everywhere conformably on

the Lower Greensand.

Many Foraminifera have been found in the Gault,

and a few Corals, Cyclocyathus Fittoni, Trochosmilia

sulcata, and Caryophyllia Bowerbankii. Its sea-urchins

are of the genera Cidarius (C. Gaultina), Hemiaster

(H. Asterias, H. Baileyi), and Diadema tumida. It

contains many Crustaceans, such as Astacus, Etyus Martini, Diaulax

Carteriana,

Palœocorystes Stokesii, &c. Among the Brachiopoda and

Lamellibranchiate

[Gault. 219]

molluscs the following are characteristic :—Terebratula

biplicata, Rhynchonella sulcata, Oysters, Pectens,

Plicatula pectinoides, Pinna tetragona, &c. ; Gervillia

solenoides, Inoceramus sulcatus, &c.;

Lima parallela, Cucullœa, Arca, Nucula pectinata, &c. it also

yields Gasteropoda of the genera

Dentalium, Solarium, Scalaria, Natica Gaultina, Pleurotomnaria

Gibbsii, Rostellaria

carinata, &c., and many Cephalopoda, such

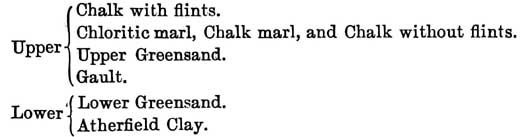

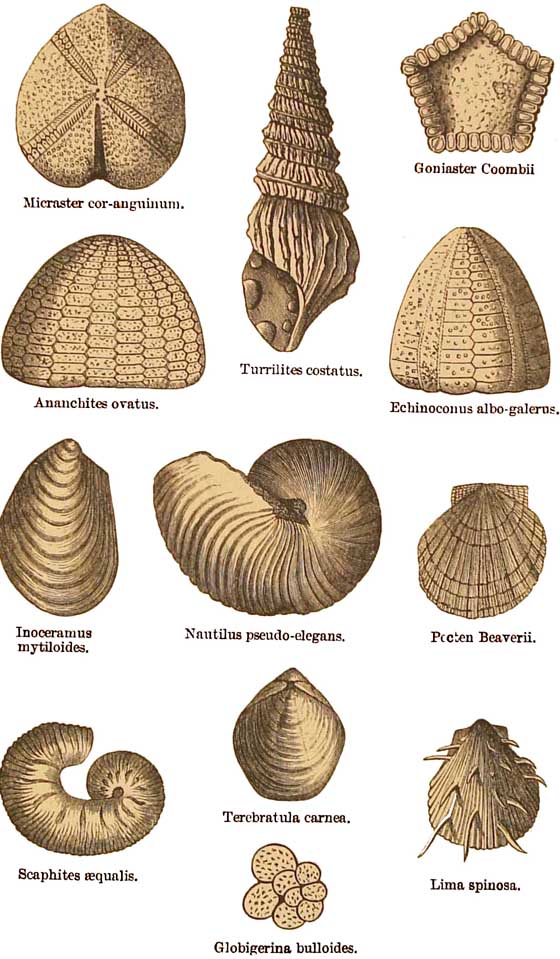

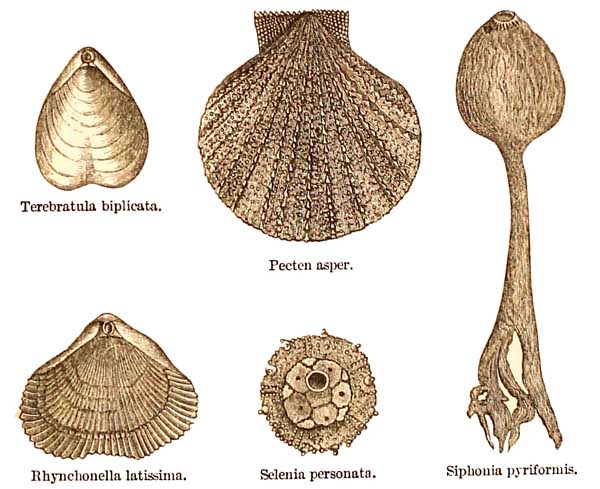

FIG.

43.

Group of Gault Fossils.

as Belemnites minimus, &C. ; Nautilus inequalis,

&c. ; Ammonites splendens, A. dentatus, A.

interruptus, A. lautus, &c. &c. ; Ancyloceras

spinigerum, Hamites attenuatus; H. rotundus,

&.c. Traces of the Gault may probably be found along the lower

outskirts of the Chalk all the way

to Filey Bay in Yorkshire, where the Red Chalk has by some been

considered to be its equivalent,

or, at all events, to be of a

[220

Upper Greensand.]

geological date, not later than its successor the Upper Greensand.

It would be a great comfort to a proportion of the geological

population, if the different

formations were as clearly distinguishable on the ground, as they are

on a map, by different

colours, aided by numbers or letters for the use of the colour-blind.

If to this, in the economy

of Nature, it had so happened that no species had been permitted to

stray from its own formation

into the next in succession, the benefit would have been much enhanced,

for to those with keen

eyes for form, the finding of any single fossil would be sufficient to

mark the place in the

geological scale of any given formation. Then we should have a perfect

and orderly symmetrical

accuracy of detail, so that he who runs may read. But it so happens

that this is not the case, for

Nature loves variety, and performs her functions in various ways, and

thus it happens that in

certain cases the dividing lines between two formations, if we follow

them far enough, are

sometimes difficult to determine. Of these unruly formations in England

the Upper Greensand

forms one, in its occasional physical relations to its neighbours, the

Gault below and the Chalk

above.

THE UPPER GREENSAND in the West of England appears in great force,

forming part of the

strata that extend from the coast between Lyme Regis and Sidmouth,

northward to the Black

Down Hills, south of Taunton. West of the estuary of the Exe, it forms,

in two outlying patches,

the broad-topped hills of Great Hal-don and Little Hal-don, and south

of the angle of the Teign,

near Newton Bushell, there is another outlier on Milber Down. These lie

so near the main mass,

and approximately are so much on the same level, that they

[Upper Greensand. 221]

are obviously the work of ordinary denuding agencies on a broader area

of Greensand. It is,

however, at first sight somewhat surprising, to meet with a small

outlier of Upper Greensand,

only a few acres in extent, nearly fifty miles to the west of Black

Down, at Orleigh Court, three

miles south-east of Bideford Bay. This patch is mentioned by De la

Beche, in his Report on the

Geology of Cornwall, Devon, and West Somerset, and of late its

existence as a solid outlier has

been doubted. There is, however, so much angular chert on the spot,

that sufficient material

remains to show that the Greensand once spread westward so far, and in

my opinion probably

much farther,

Throughout these areas, the Upper Greensand may be briefly described as

consisting of

yellowish brown sand, partly compact, partly soft, with layers and

detached pieces of chert, and

towards the base it is partly green with specks of silicate of iron.

The sands are often coarse,

and contain layers of shells, frequently broken and fragmentary. The

whole is little more than

200 feet in thickness.

East of Lyme Regis, this Greensand appears near Abbotsbury, on the

southern and western

flanks of the Chalk Downs at Whitehill. West of Chideock outlying

patches lie on the maristone of

the Middle Lias, between Chideock and Bridport on the sand that

underlies the Inferior Oolite, at

Abbotsbury Castle on the Forest Marble, and from thence stretching

north and west, at Shipton

Beacon they lie on the Fuller's Earth. Beyond this the Cretaceous

strata make a great. curve east

of Poorstock and Beaminster, lying generally on the Fuller's Earth.

East of Cheddingtori, for

some miles the Greensand lies on the Oxford Clay, then for a short

space on the sand of the

Calcareous

[222 Upper Greensand.]

Grit, then from Buckland Newton, in Dorsetshire, to the neighbourhood

of Shaftesbury, on

Kimeridge Clay.

Near Shaftesbury the Gault comes on in force, and separates the Upper

Greensand from the

Oolitic rocks as far as the neighbourhood of East Knoyle, on the north

side of the mouth of the

Vale of Wardour. Between East Knoyle and Chapmanslade in Wiltshire, the

Greensand lies

chiefly on the Coral Rag, but partly on the underlying Oxford Clay, and

the Gault, if present at

all, is so thin that it cannot be mapped. It is probable that when the

Gault was deposited

elsewhere, this part of the Oolitic area was above the sea-level. From

Chapmanslade, the

Greensand, underlaid by Gault, runs along the lower part of the Chalk

escarpment in an ENE.

direction, by Westbury to Urchfont and Devizes, and from thence, lying

nearly flat, the strata

form the surface of a broad tract of country, eighteen miles in length

from west to east, bounded

on both sides by Chalk, the whole forming a low anticlinal north and

south curve. Still further

east, at Shalbourne and Sidmonton, near .Kingsclere in Hampshire, two

other tracts of Upper

Greensand rise through the Chalk to the surface in anticlinal curves of

an oval form.

Between Devizes, the Fens of Cambridgeshire, and the east coast of the

Wash, the Upper

Greensand runs to the north-east, in a long somewhat sinuous line, and

nearly all along the

strike it forms the lower part of the bold escarpment of the Chalk,

which overlooks the great

plain or table-land of Oolitic strata that runs across England from the

coast of Dorsetshire to

the Humber. North of the Humber, it is marked in ordinary maps as

skirting the Chalk Wolds,

first to the north and then to the east, as far as Filey Bay, but if

such be the case, its sandy

character is not always

[Upper Greensand. 223]

easily recognisable, which, indeed, is also the case much further south.

In the south-eastern part of Dorsetshire, the Upper Greensand crosses

the Isle of Purbeck from

west to east in a narrow line, overlying the well-known Punfield beds,

and overlaid by the

Chalk of the long and imposing ridge of Purbeck Hill, Knowl Hill, Nine

Barrow Down, and

Ballard Down. The Greensand itself makes no feature in the landscape.

Fig. 75, p. 347.

Striking

east under the sea,

the Upper Greensand barely escapes forming part cf the great seacliff

of

chalk, that runs from Sun Corner near the Needles, to Compton Bay below

Afton

Down, from whence, overlying the Gault, it crosses the Island to the

sea

close under Bembridge Down. In this course, wherever the Chalk Downs

are

narrow, owing to the high angle of northern dip, there the line of

Upper

Greensand is also narrow, but where the angle of inclination is

comparatively

low, there both Chalk and Greensand spread over a broad space, between

Mollestone

Down and Carisbrook. A large outlier of Upper Greensand, capped by two

outliers

of Chalk, overlooks the sea on the south side of the Island between

Chale

Bay and Chine Head, the strata being nearly flat.

In the area of the Weald of Kent and Sussex (fig. 72), the Upper

Greensand at the base of the

escarpment of the Chalk, sweeps round the vast oval, from East Wear

Bay, near Folkestone, to

East Meon, near Petersfield, and from thence to the sea at Eastbourne,

near Beechy Head, but not

with absolute certainty all the way, for only here and there can the

Greensand be faintly

discovered, between the sea and Chevening, along a line of about fifty

miles in length. Beyond

this point it begins to get more distinct, and the malm-rock,

fire-stone,

[224

Upper Greensand.]

and other

lithological varieties, can be traced all along by Westerham, Merstham,

Guildford, the Hog's Back, Farnham, and the extreme west of the area in

the country round

Binstead, Selbourne, and the ground about two miles west and south of

Petersfield, where, as far

as colour goes, it might often be taken for chalk.

On the south side of the Wealden area, the Upper Greensand maintains

the same general

character by Cocking and Barlavington as far as Steyning, where its

lithological character

begins to change, and the beds pass into 'sandy marl and marly sand,'

and near Eastbourne the

strata are decidedly sandy.

Important deductions are to be drawn from the consideration of the

lithological changes that take

place in the character of the Upper Greensand, which will afterwards

appear. A gradual change

may be traced all the way from Devonshire to Cambridgeshire and the

east end of the Wealden

area, which throws some light on the physical geography of the time,

especially when taken in

connection with the circumstance, that out of more than 200 species of

fossils in the Gault,

about 46 per cent. pass onward into the Upper Greensand.1

The Upper Greensand is often

fossiliferous, containing Cycads and Coniferous woods;

Sponges, Siphonia, pyriformis, &c.; a

few Foraminifera; Corals, Trochosmilia tuberosa, Micrabacia coronula;

many Echinoidea, the

chief of which belong to the genera Cidaris, Cardiaster, Echinus,

Pseudo-diadema, Salenia,

&c. Brachiopoda are common, Terebratulœ and Rhynchonellœ (T.

biplicata, Rh. latissima,

1 For much information

on the Upper Greensand of the Wealden area see 'Memoirs of the

Geological Survey, Geology of the Weald,' by W. Topley, 1875.

[Upper Greensand. 225]

&c.). In Lamellibranchiate molluscs it is even richer than the

Lower Greensand, abounding

especially in species of the genera Inoceramus, Gryphœa (1avigata),

Lima, Pecten asper,

Astarte, Trigonia, Cucullœa, Cyprina, and Cytherea. It is

also rich in Gasteropoda, such as

Turritella, Pleurotomaria, Natica (Y. Gentii),

&c., and yields many species of Ammonites, Nautili,

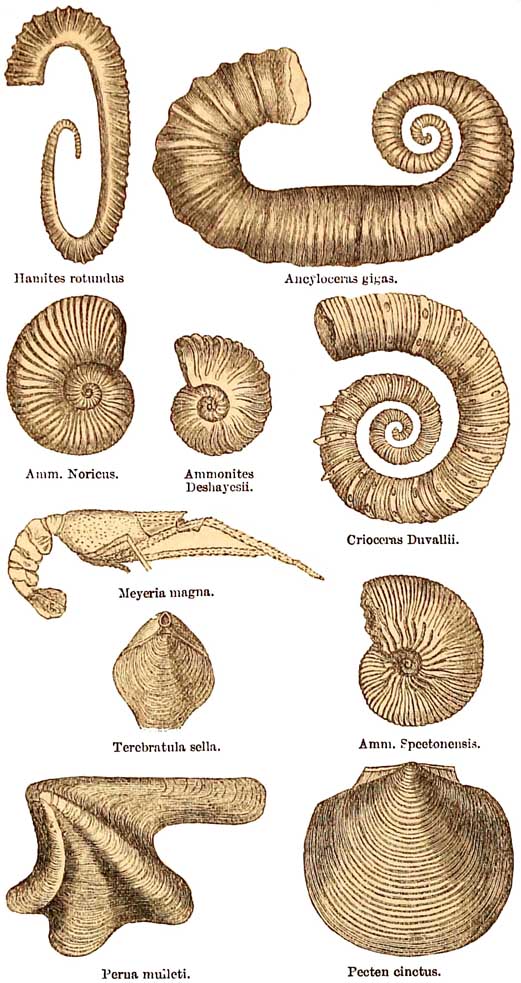

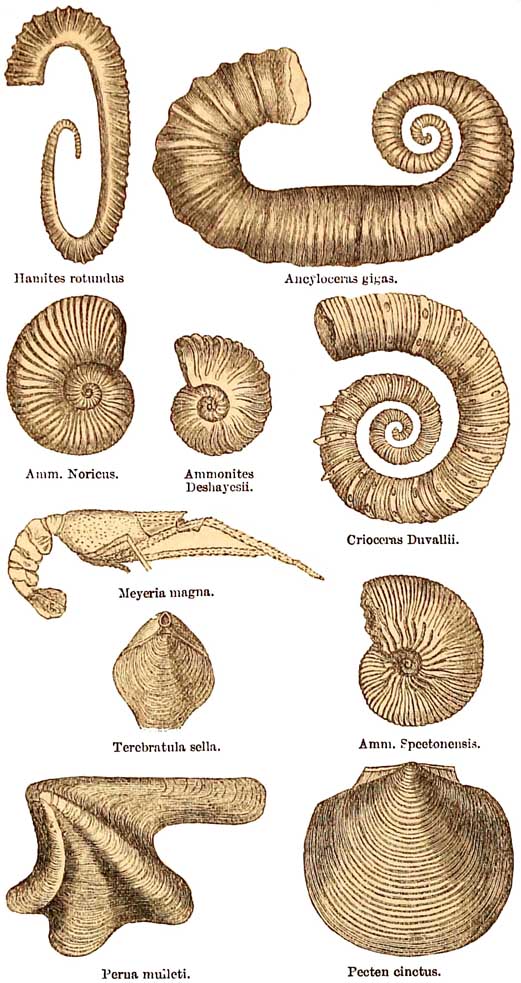

FIG.

44.

Group of Upper Greensand Fossils.

Hamites,

Baculites, Scaphites, and Belemnites. Crustacea, Hoploparia

longimana, Necrocarcinus Bechii, &c. Probably three species of

Reptilia belong to this formation,

Plesiosaurus pachycomus, a Crocodile,

and a Turtle.

THE CHALK, from its familiar characters and general uniformity of

structure, is the most

easily recognisable

[226 Chloritic and Chalk Marl.]

of all the British formations. From west to east it stretches from the

neighbourhood of

Beaminster in Dorsetshire, to Beachy Head and the North Foreland, and

passing beneath the

Eocene formations of the Hampshire and London basins it spreads

northward to Speeton, in

Yorkshire.

The Chloritic Marl indicates a passage from the Upper

Greensand into the Chalk. It consists of a

chalky base specked with green grains, and varies from a few inches to

a few feet in thickness.

It is highly fossififerous, abounding in Ammonites, Nautili (N.

lœvigata), and a small Scaphite

(S. œqualis), besides Oysters, Trigonias, Holaster,

&c., and many other Echinodermata.

The Chalk Marl, which lies above the Chloritic Marl when both

are present, is merely chalk

with a slight admixture of argillaceous matter, and with its

predecessor by no means deserves

to be considered as a separate formation. The whole, therefore, may be

massed as The Chalk. It

consists of a soft white limestone, generally much jointed where

exposed in quarries, and but

for lines of flints, the bedding would often be scarcely

distinguishable. On minute examination

with the microscope, much of the Chalk is found to consist of the

shells of Foraminifera,

Diatomaceæ, spiculæ and other remains of Sponges, Polyzoa,

and shells, highly comminuted.

Somewhat similar deposits are now forming in the open Atlantic at great

depths, chiefly of

Foraminifera of the genus Globigerina, Polycystina and

Diatomaceæ, and spiculæ of Sponges. In

the Pacific, also, from Java to the Low Archipelago, over an area of

about 4,000 miles in

length, all the deep-sea deposits are of fine, white, calcareous mud,

like unconsolidated chalk.

In its thickest development in England the Chalk is

[The

Chalk. 227]

about 1,200 feet thick in Dorsetsliire, Hampshire, &c. The Lower

Chalk usually contains no

flints and,as already stated, is somewhat many at the base, while the

Upper Chalk is

interstratified with many beds of interrupted flints. These are of

irregular form, and lie in

layers in the lines of bedding. A great proportion of them are stated

by Dr. Bowerbank to be

silicified Sponges, which often inclose other organic bodies, such as

shells, fragments of

Belemnites, &c.; others of large size, called Paramoudras, which

are rare, stand vertically

across the beds. These sometimes resemble, in general form, the large

cup-shaped sponges of

the Indian Ocean Alcyonium, or Neptune's cup.

As a whole, the Chalk dips gently from its western escarpment to the

east and south, and round

the Wealden area to the south and north, underlying the Tertiary strata

of the Hampshire and

London basins, and reappearing with precisely the same characters on

the coast of France. Its

area in Europe and Asia is immense. In the north of Ireland, between

Belfast and the Giant's

Causeway, there are patches of very hard Chalk on the coast, overlaid

by columnar basalt of

Miocene age. The great superincumbent pressure of these masses of

igneous rocks has hardened

the chalk, and therefore they have not, as is usually supposed, been

altered by the heat of

overflowing lavas, except possibly for an inch or two at the immediate

point of junction, but

this is somewhat foreign to our present subject. Traces of Chalk and

Upper Greensand occur at

Bogingarry, &c., in Aberdeenshire. These consist partly of chalk

flints, partly of sandstone,

possibly in place, and sufficient to show that Cretaceous rocks, which

have been removed by

denudation, probably once spread over that country. Cretaceous strata,

discovered by Mr.

[228 The Chalk]

Judd, also occur in the Island of Mull beneath the Miocene basalts.

About half the genera, and a considerable number of Chalk species, are

identical with those of

the Gault and Upper Greensand, but it contains a far greater number,

nearly 800, most of

which are peculiar to itself. Plants are few, as might he expected in a

wide deep-sea deposit. A

great many Sponges have been described, chiefly from flints. Among the

most numerous are

species belonging to the genera Ventriculites, Gephalites, Spongia,

and Siphonia. A large number

of genera and species of Foraminifera are also described, among which Globigerina

bulloides,

Dentalina gracilis, and Rotalina ornata, are common. Of

Corals about 15 species are known,

several of which belong to the genus Parasmilia (centralis,

&c.), Caryophillia lœvigata, &c.

Echinodermata are very numerous, among others including the genera Ananchytes,

Cardiaster, Cidaris, Cyphosoma, Diadema, Echinopsis, Galerites and

Echinobrissus, Holaster, Micraster,

and Solenia, &c. Among its starfish are comprised the

genera Arthraster, Goniaster, and

Oreaster. Of these Goniaster is exceedingly characteristic. In

addition it has yielded an Ophiura

and several Crinoids, Bourgueticrinus ellipticus, Marsupites Milleri,

&c. On shells, &c.,

found in the Chalk, are frequent Serpulæ. It also yields

Cirripeds and a few Crustaceans,

Enoploclytia Sussexensis &c. Polyzoa are numerous, of many

species. Like other members of

the Cretaceous rocks, its Brachiopoda generically resemble those of the

Oolites, including

Rhynconella, Terebratulina, and Terebratula. The

Lamellibranchiate molluscs of the Chalk are

in some cases specifically identical with those of the Gault and Upper

Greensand; and,

generically, they bear the

[229]

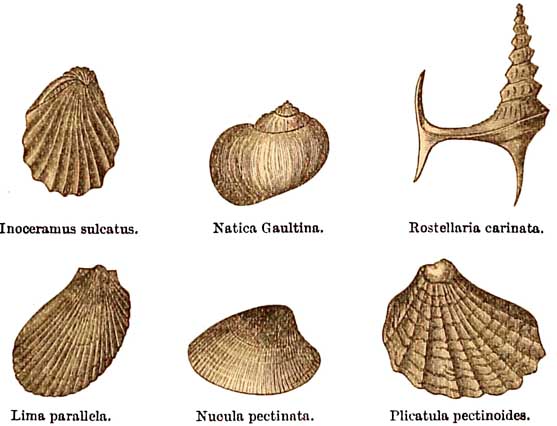

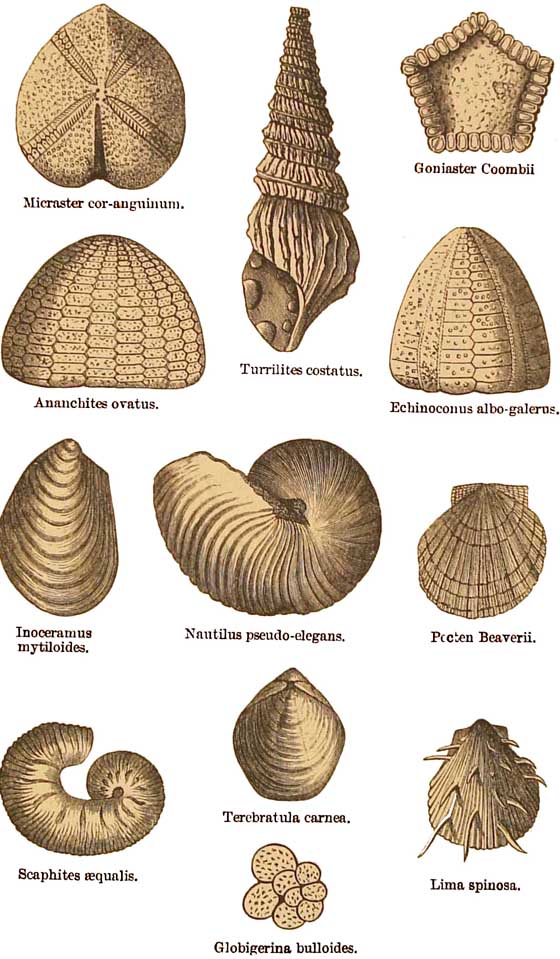

FIG.

45.

Group of Fossils from the Chalk.

[230

The chalk.]

strongest resemblance, consisting, among others, of

many species of Inoceramus, Lima, Pecten, Oyster,

Spondylus, Radiolites, Trigonia, &c. Being a deepsea deposit,

it is poor in Gasteropoda, but rich

in Cephalopoda, especially in Nautili (N. elegans, &c), Ammonites

(A. Rothomagensis, &c.),

and Turrilites (T. costatus), besides Baculites, Hamites

simplex, Scaphites (S. œqualis), and

Belemnites.

Numerically as individually, though still very characteristic,

Cephalopoda are less numerous in

the Cretaceous than in the Oolitic and Liassic strata, though the

latter contain fewer genera. In

the Lias and Oolites there are nearly 300 species of Cephalopoda, most

of which are Ammonites.

In the Cretaceous rocks less than 200 species are known, about 70 of

which are Ammonites.

More than 80 species of fish are known in the Chalk, including all the

four orders of Agassiz,

Placoids, Ganoids, Cycloids, and Ctenoids. Many of the Placoids are

Cestraciont fish, numerous

species being of the genus Ptychodus. Ten genera of reptiles are known,

two of which are allied

to the Crocodilia, Acanthophilis horridus, and Leiodon anceps

; the great Mosasaurus, 3

species; Plesiosaurus, 2 species, Ichthyosaurus and Pterodactyle,

one of which is said to have

measured eighteen feet across the expanded wings. Several Turtles occur

in the Chalk, Chelone

Bertstedi, &c.

Having thus briefly described the Tipper Cretaceous strata of England,

I shall next endeavour to

show what inferences may be drawn with regard to the physical geography

of the British area,

during the time occupied by their deposition.

We have already seen that, during the deposition of the Purbeck and

Wealden strata, England

formed part

[Physical Geography. 231]

of a great continent, and that, during the formation of the Lower

Greensand, this land suffered

partial submergence, but by no means to such an extent that the Oolitic

strata, which then

extended far to the west, round Wales, were entirely sunk beneath the

sea in which our Lower

Greensand was deposited.

As a whole, the Lower Greensand, being a coarse and sandy formation,

was deposited in shallow

water, and great part of it was in the long run tranquilly heaved out

of the sea, to undergo

terrestrial waste and denudation before the deposition of the Gault

began.

The deposition of the Gault in our area, first took place on a surface

of country that was being

gradually submerged, and part of the sediment was laid on the Lower

Greensand, and part on

various members of the Oolitic strata, from which the Lower Greensand

had been removed by

denudation. This Gault Clay is, however, so difficult to separate from

the Upper Greensand in the

eastern part of England, and the Upper Greensand is so difficult to

separate by any clear line

from the Chalk, that it now becomes necessary to consider the question

of the mode of deposition

of all three, if, indeed, except as local developments of different

sedimentary character, they

ought not to be considered, on a broad scale, as only one formation.

Right or wrong, the origin of

this idea was first declared by Mr. Godwin-Austen, whose large grasp of

questions in physical

geology, (to be found only in scattered memoirs, and unfortunately

often only spoken in

accidental remarks,) is by no means so well known as it would have

been, had he printed all his

stores of geological knowledge in consecutive form. All that I know of

this subject with respect

to these Cretaceous formations, is in the first

[232 Physical Geography.]

instance derived from him, subsequently aided by personal observation

on the ground.

The story revealed by these various strata is this: When, after the

temporary upheaval of the

Lower Greensand, the land gradually sank in part beneath the sea, it

happened that the Upper

Greensand was being deposited far in the west on a sea-bottom that now

forms an eastern part of

Devonshire. Not far from its margin, a fragment of the old greater

land, in our day known in a

modified form as the granite hills of Dartmoor, stood high above the

level of the sea, and at the

same time, on the opposite side of what is now the Bristol Channel,

Wales also formed high land.

The pebbly shore of the lower land near Dartmoor, has long ago been

destroyed by denudation,

but the sediments laid down not far from the shore still exist in the

coarse sandy strata that

form the Upper G-reensand west and east of the river Exe. As we go

eastward from that area

towards Devizes, the Upper Greensand still continues to be

comparatively coarse, and by

degrees in Buckinghamshire, and Bedfordshire, and on into

Cambridgeshire, it gets finer and

finer, and at length becomes white, calcareous, and marly, and, as it

were, seems to mingle with

the Gault beneath and the Chalk above, and the Gault, indeed, in a

lithological point of view,

sometimes seems to disappear altogether.

In like manner, at the western end of the Wealden area, and along the

base of the South and North

Downs, the Upper Greensand for many miles consists of fine, white sand,

and in the Malm-rock

is somewhat chalk-like and calcareous, till going further east towards

Folkestone, it gradually

becomes untraceable as a special formation, and merges into the

underlying Gault and the

overlying Chalk.

[Physical Geography. 233]

The meaning of this is, that distinct coarse Upper Greensand strata

were deposited not far from

shore in the west, gradually getting finer towards the east, because

the finer and lighter

material was drifted further from shore. At the very same time, in the

farther east of what is

now England, the sediments were still finer, and depositions akin to

Chalk, and even the Chalk

itself, had begun to be formed in a deeper sea, far removed from land,

so that according to this

view, part of the lowest strata of the Chalk, in the eastern and

southeastern parts of England,

were deposited contemporaneously with the coarse Upper Greensand of

eastern Devonshire. On

no other hypothesis that I know than this of Godwin-Austen's, can the

phenomena connected with

the Gault, Upper Greensand, and the lower strata of the Chalk, be

rationally accounted for, and I

believe that hypothesis to be true.

The upper strata of the Chalk consist of nearly pure chalk with lines

of flint, and as it

accumulated, the sinking of the western and northern fragments of the

old continent steadily

continued, till at length they almost, if not entirely, sank beneath a

sea, broad and silent,

except when roused by storms, like the Atlantic of our own time, for

though the Echini and

shells found in our chalk, show that the sea of those days was not so

deep as the present Atlantic,

yet the prevalence of prodigious numbers of Globigerina and other

Foraminifera shows that the

old and the new seas are akin in the nature of their organic sediments.

If the whole of the older

land was not submerged, (making an allowance for the lowering of the

mountain lands by

subsequent subaerial waste,) even then we can only suppose that a few

insignificant islets rose

above a waste of waters, that spread not only over Britain, but also

[234 Physical Geography.]

over a very large part of the Europe of the present day, long before

the Alps and the Pyrenees

rose into mountain chains, and only a few islands formed of

Palæozoic rocks stood above the

waves. This surely was a striking phase of an older physical geography,

which affected areas far

wider than Europe alone, but which in the course of time came to an end

in a manner which we

shall presently see. To do so thoroughly we must consider the rocks of

the continent for a little.

A vast lapse of time took place between the close of the deposition of

the uppermost Cretaceous

strata of England, and the commencement of the deposition of the

succeeding Eocene formations,

for in England we have no deposits of intermediate age. What, however,

helps to prove this great

hiatus is, that on the Meuse, at Maestricht, there is a calcareous

formation about 100 feet

thick, which lies unconformably on the Chalk, the line of unconformity

being marked by a line

of water-worn flint pebbles. Some of the fossils are of the same

species with those found in the

Chalk, and Cephalopoda of the genera Baculites and Hamites,

not yet known in strata younger

than the Cretaceous rocks of Europe, are found in the Maestricht beds.

On the other hand,

Volutes, and other genera of Tertiary type, are found in the strata, so

that this marine fauna

may be said to be of a type intermediate to those of the Cretaceous and

Eocene epochs.

Extending for great distances round Paris, there are numerous small

patches of pisolitic

limestone, once united, but now separated by denudation. These contain

some Cretaceous species,

but many others are more Eocene than Cretaceous in their affinities.

At Faxoe also, in the Isle of Seeland, in Denmark, there is a yellow

limestone so full of corals

that it was

[Physical Geography. 235]

probably a coral reef. It contains among other shells many univalves

which are unknown or

rare in the Chalk, such as Cyprœa, Oliva, &c., and along

with these Baculites and Belemnitella,

both unknown in European Eocene strata, though the latest intelligence

from Australia tells of a

Belemnite in certain late Tertiary strata there. Overlying the common

white Chalk, this Faxoe

formation by its fauna also seems to be intermediate in date to the

ordinary Cretaceous and

Eocene strata.

But without such data as these it is evident to any reflective mind,

that a great gap in time,

unrepresented by any sedimentary formations in England, took place in

our area between the

deposition of the latest bed of English Chalk, and that of the earliest

Eocene stratum, for,

excepting a few Foraminifera, the species found in the Chalk seem all

to have been remodelled

before our Eocene epoch began, in so far that palæontologists

recognise none of the species as

identical, and before the days of Darwin they would generally have been

spoken of as new

creations.