THE following Lectures, with The Cruise of the Betsey, and Rambles of a Geologist; are all that remain of what Hugh Miller once designed to be his Maximum Opus, — THE GEOLOGY OF SCOTLAND. It is well, however, that his materials have been so left that they can be presented to the public in a shape perfectly readable; furnishing two volumes, each of which, it is hoped, will be found to possess in itself a uniform and intrinsic interest, — differing in matter and manner as much as they do in the form in which they have found an embodiment. That form is simply the one naturally arising out of the circumstances of the Author's life as they occurred, instead of the more artificial plan designed by himself; in which these circumstances would probably more or less, if not altogether, have disappeared. Yet it may well be doubted whether the natural method does not possess a charm which any more formal arrangment would have wanted. Every one must be struck with the freshness, buoyancy, and vigour displayed in the Summer Rambles; qualities more apparent in these than even in his more laboured Autobiography, of which they are, indeed, but a sort of unintentional continuation. They were the spontaneous utterances of a mind set free from an

[xiv PREFACE.]

occupation never very congenial, — that of writing compulsory articles

for a newspaper, — to find refreshment amid the familiar haunts in

which it delighted, and to seize with a grasp, easy, yet powerful, on

the recreation of a favourite science, as the artist seizes on the

pencil from which

he has been separated for a time, or the musician on some instrument

much

loved and long lost, which he well knows will, as it yields to him its

old

music, restore vigour and harmony to his entire being. My dear husband

did,

indeed, bring to his science all that fondness, while he found in it

much

of that kind of enjoyment, which we are wont to associate exclusively

with

the love of art.

The delivery of these Lectures may not yet have passed quite away

from the recollection of the Edinburgh public. They excited unusual

interest, and awakened unusual attention, in a city where interest in

scientific

matters, and attendance upon lectures of a very superior order, are

affairs

of every-day occurrence. Rarely have I seen an audience so profoundly

absorbed.

And at the conclusion of the whole, when the lecturer's success had

been

triumphantly established (for it must be remembered that lecturing was

to him an experiment made late in life), I ventured to urge

the

propriety of having the series published before the general interest

had

begun to subside. His reply was, 'I cannot afford it: I have given so

many

of my best facts and broadest ideas, — so much, indeed, of what would

be

required to lighten the drier details in my Geology of Scotland —

that

it would never do to publish these Lectures by themselves.' It will

thus

be seen that they veritably gather into one luminous centre the best

portions

of his contemplated work, garnering very much of what was most vivid in

painting and

[PREFACE xv]

original in conception, — of that which has now, alas! glided, with

himself, into those silent shades where dwell the souls of the

departed, with the halo of past thought hovering dimly round them,

waiting for that new impulse from the Divine Spirit which is to quicken

them into an intenser and higher unity.

I have been led to indulge the hope that this work will be found

useful in giving to elementary Geology a greater

attractiveness in the eyes of the student than it has hitherto

possessed. It was characteristic of

the mind of its author that he valued words, and even facts, as only

subservient to the high powers of reason and imagination. It is to be

regretted that many introductory works, especially those for the use of

schools, should be so crammed with scientific terms, and facts hard

packed, and not always well chosen, that they are fitted to remind us

of the dragon's teeth sown by Jason, which sprang up into armed men, —

being much more likely to repel, than to allure into the temple of

science. One might, indeed, as well attempt to gain an acquaintance

with English literature solely from the study of Johnson's

Dictionary, as to acquire an insight into the nature of Geology from

puzzling

over such books. But, viewed in the light of a mind which had

approached

the subject by quite another pathway, all unconscious, in its outset,

of

the gatherings and recordings of others, and which never made a single

step

of progression in which it was not guided by the light of its own

genius

and the inspiration of nature, it may be regarded by beginners in

another

aspect, — one very different from that in which Wordsworth looked upon

it

when he thanked Heaven that the covert nooks of nature reported not of

the

geologist's hands, — 'the man who classed his splinter by

[xvi PREFACE.]

some barbarous name, and hurried on.' At that time the poet must have

seen but the cold, hard profile of the man, instead of the broad,

beaming,

full-orbed glance which he may cast over the wondrous æons of the

past eternity.

To meet any difficulties arising from misconception, it may be

proper

to glance rapidly at what has been accomplished in geological research

within the last two years. The reader will thus avoid the painful

impression that there are any suppressed facts of recent date which

clash with the theories of the succeeding Lectures, destroying their

value and impairing their unity. And it may be well to remind him that

there are two schools of Geology, quite at one in their willingness to

bring all theories to the test of actual discovery, but widely

differing in their leanings as to the mode in which, a priori, they

would wish the facts brought to light to be viewed. The one, as

expounded in the following Lectures, delights in the unfolding of a

great plan, having its original in the Divine Mind, which has gradually

fitted the earth to be the habitation of intelligent beings, and has

introduced upon the stage of time organism after organism, rising in

dignity, until all

have found their completion in the human nature, which, in its turn, is

a

prophecy of the spiritual and Divine. This may be said to be the true

development

hypothesis, in opposition to the false and puerile one, which has been

discarded

by all geologists worthy of the name, of whatsoever side. The other

school

holds the opinion, — though perhaps not very decidedly, — that all

things

have been from the beginning as they are now; and that if evidence at

the

present moment leans to the side of a gradual progress and a serial

development,

it is because so much remains undiscovered; the hiatus, wherever it

occurs,

being

[PREFACE. xvii]

always in our own knowledge, and not in the actual state of things. The next score of years will probably bring the matter to a pretty fair decision; for it seems impossible that, if so many able workers continue to be employed as industriously as now in the same field, the remains of man and the higher mammals will not be found to be of all periods, if at all periods they existed. In the meantime, it is well to know the actual point to which discovery has conducted us; and this I have taken every pains most carefully to ascertain.

The Upper Ludlow rocks, — the uppermost of the Silurians, — continue to be the lowest point at which fish are found. Up to that period, — during the vast ages of the Cambrian, where only the faintest traces of animal life have been detected1 in the shape of annelides or sand-boring worms, — throughout the whole range of the Silurians, where shell-fish and crustaceans, with inferior forms of life, abounded, — no traces of fish, the lowest vertebrate existences until the latest formed beds of the Upper Silurian, have yet appeared. There are now six genera of fish ranked as Upper Silurian, — Auchenaspis, Cephalaspis, Pteraspis, Plectrodus, Onchus Murchisoni, and Sphagodus. The two latter, — Onchus Murchisoni and Sphagodus, — are represented by bony defences, such as are possessed by placoid fishes of the present day. Sir Roderick Murchison at one time entertained the idea of placing the Ludlow bone-bed at the base of the Old Red Sandstone; but its fish having been found decidedly associated with Silurian organisms, this idea has been abandoned.

1 See the lately published edition of Sir

Roderick I. Murchison's Siluria, chap. ii. p. 26.

[xviii PREFACE.]

The next point to which public attention has been specially directed is the discovery of mammals lower than they had formerly appeared. Considerable misconception has arisen on this head. The Middle Purbeck beds, recently explored by Mr. Beckles, in which various small mammals were found, occur considerably farther up than the Stones-field slates, in which the first quadruped was detected so far back as 1818. But this discovery involves no theoretical change, inasmuch as all the mammalian remains of the Middle Purbecks consist of small marsupials and insectivora, varying in size from a rat to a hedgehog, with one or two doubtful species, not yet proved to be otherwise. The living analogue of one very interesting genus is the kangaroo rat, which inhabits the prairies and scrub-jungles of Australia, feeding on plants and scratched-up roots. Between the English Stonesfield or Great Oolite, in which many years ago four species of these small mammals were known to exist, and the Middle Purbeck, quarried by Mr. Beckles, in which fourteen species are now found, there intervene the Oxford Clay, Coral Rag, Kimmeridge Clay, Portland Oolite, and Lower Purbeck Oolite; and then, after the Middle Purbeck, there occurs a great hiatus through out the Weald, Green Sand, Gault, and Chalk, wherein no quadrupedal remains have been found; until at length we are introduced, in the Tertiary, to the dawn of the grand mam malian period; so that nothing has occurred in this department to occasion any revolution in the ideas of those who, with my husband, consider a succession and development of type to be the one great fixed law of geological science. The reader will see that in the end of Lecture Third such remains as have been found lower than the Tertiary are

[PREFACE. xix]

expressly recognised and excepted. 'Save,' says the author, 'in the

dwarf and inferior forms of the marsupials and insectivora, not any of

the honest mammals have yet appeared.'

But while attaching no importance to the discoveries in the Middle

Purbeck, except in regard of more ample numerical development, it is

necessary

to admit the evidence of marsupials having been found lower than the

Stonesfield or Great Oolite : even so far back as the Upper Trias, the

Keuper Sandstone of Germany, which lies at the base of the Lias. I must

be permitted, on this point, to quote the authority of Sir Roderick

Murchison, as one of

the safest and most cautious exponents of geological fact. 'In that

deposit,' says he, referring to the Keuper Sandstone of

Würtemberg, 'the relics of a solitary small marsupial mammal have

been exhumed, which its discoverer, Plieninger, has named Microlestes

Antiquus. Again, Dr. Ebenezer Emmons, the well-known geologist of

Albany, in the United States, has described,

from the lower beds of the Chatham Secondary Coal-field, North Carolina

(of

the same age as those of Virginia, and probably of the Würtemberg

Keuper), the jaws of another minute mammal, which he calls Dromotherium

Sylvestre. Lastly, while I write, Mr. C. Moore has

detected in an agglomerate which fills the fissures of the

carboniferous limestone near Frome, Somersetshire, the teeth of

marsupial mammals, one of which he considers to be closely

related to the Microlestes Antiquus of Germany, and Professor

Owen

confirms the fact. From that coincidence, and also from the association

with other animal remains, — the Placodus (a reptile of the

Muschelkalk),

and certain rnollusca, — Mr. Moore believes that

[xx PREFACE.]

these patches represent the Keuper of Germany. If this view should be

sustained, this author, who has already made remarkable additions to

our

acquaintance with the organic remains of the Oolitic rocks and the

Lias,

will have had the merit of having discovered the first traces of

mammalia

in any British stratum below the Stonesfield slates.' . . . 'Let me

entreat,'

says Sir Roderick, in a passage occurring shortly after that we have

quoted,

— ' Let me entreat the reader not to be led, by the reasoning of the

ablest physiologist, or by an appeal to minute structural affinities,

to impugn the clear and exact facts of a succession from lower to

higher grades of life in each formation. Let no one imagine that

because the bony characters in the jaw and teeth of the Plagiaulax of

the Purbeck strata are such as the

comparative anatomist might have expected to find among existing

marsupials, and that the animal is therefore far removed from the

embryonic archetype, such an argument disturbs the order of succession

of classes, as seen

in the crust of the earth.'

So far from disturbing the order of succession, it is, we conceive, of exceeding interest to find the Mesozoic period marked in its commencement, as it most probably will be found to be, by the introduction of a form of being so entirely different from any that preceded it. It seems to us to bring the true development hypothesis into a clearer and more harmonious unity. The great period during which the little annelide or sand-boring worm was the sole tenant of this wide earth, — its first inhabitant after the primeval void, — has passed. The æon of the Mollusc and the Crustacean follows. At its close appear the first fishes, very scanty in point of numbers and of species, but

[PREFACE. xxi]

multiplying into many genera, and swarming in countless myriads, as the

Devonian ages wear on. Again, towards the termination of the latter

appear the first reptiles, which, during the Carboniferous and Permian

eras, reign as the master-existences of creation. But Pakeozoic or

ancient life passes away, and the Mesozoic or Middle period is marked,

not only by countless forms, all specifically, and many of them

generically, new, but by another wholly unknown, either as genus or

species, during all the past.

The little marsupials and insectivora appear 'perfect, after their kind,' and yet only the harbingers of the great mammalian period which is yet to come. In the volume of Creation, as in that of Providence, God's designs are wrapt in profound mystery until their completion. And yet in each it would appear that He sends a prophetic messenger to prepare the way, in which the clear-sighted eye, intent to read His purposes, may discern some sign of the approaching future.

Before we proceed, we must here, on behalf of the unlearned, and therefore the more easily misled, most humbly venture to reclaim against the use, on the part of men of the very highest standing, of the loose and dubious phraseology in which they sometimes indulge, and which serves greatly to perplex, if not to lead to very erroneous conclusions.

'In respect to no one class of animals,' says Professor

Owen, in his last Address to the British Association, 'has the

manifestation of creative force been limited to one epoch of time.'

This, translated into fact, can only mean that the vertebrate type had

its representative in the fish of the earliest or Silurian epoch, and

has continued to exist throughout all the epochs which succeeded it.

But the

[xxii PREFACE.]

difficulty lies in the translation. For at first sight the conclusion is inevitable to the general reader, that not only the lowest class of vertebrate existence, but also man and the higher mammals, had been found from the beginning, and that the highest and the lowest forms of being were at all periods contemporary. No one surely would have a right to make such a prodigious stride in the line of inference, on the presumption of supposed evidence yet to come. Again, Sir Charles Lyell, in his supplement to the fifth edition of his Elementary Geology, says, in speaking of these same Purbeck beds quarried by Mr. Beckles, 'They afford the first positive proof as yet obtained of the co-existence of a varied fauna of the highest class of vertebrata with that ample development of reptile life which marks the periods from the Trias to the Lower Cretaceous inclusive.' Are marsupials and insectivora the highest class of vertebrata?

Where, then, do the great placental mammals, — where does man himself; — take rank?

It were surely to be desired that some stricter and more invariable

form of phraseology were adopted, either in accordance with the

divisions of Cuvier, or some analogous system, adherence to which would

be clearly defined and understood. Why should not the words class,

order; type have as invariable a meaning as genera and spcies,

which, having an application more limited, are seldom mistaken? We

are aware that such terms are often used by the learned in an

indefinite and translatable sense, just as to the learned in languages

it may be a matter of indifference whether the written characters which

convey information to them be Roman, Hebrew, or Chinese. But it should

be remembered that there is a large class outside which

[PREFACE. xxiii]

seeks to be addressed in a plain vernacular, — which asks, first of all, definiteness in the use of terms to which probably they have already sought to attach some fixed sense; and that it is not well to unship the rudder of their thought, and send them back to sea again.

The next point which demands attention in our short résumé is that great break between the Permian and Triassic systems, across which, as stated in the following pages, not a single species has found its way. Much attention has been given to the great Hallstad or St. Cassian beds, which lie on the northern and southern declivities of the Austrian Alps. These beds belong to the Upper Trias, and they contain more genera common to Palæozoic and newer rocks than were formerly known. There are ten genera peculiarly Triassic, ten common to older, and ten to newer strata. Among these, the most remarkable is the Orthoceras, which was before held to be altogether Palæozoic, but is here found associated with the Ammonites and Belemnites of the secondary period.1 The appearance of this, with a few other familiar forms, serves, in our imagination at least, to lessen the distance, and, in some small measure, to bridge over the chasm, between Palæozoic and Secondary life. And yet, considering the vast change which then passed over our planet, — that all specific forms died out, while new ones came to occupy their room, — the discovery of a few more connecting generic links in the rudimentary shell-alphabet, which serve but to show that in all changes the God of the past is likewise the God of the present, no more affects in reality this one great revolution,

1 See Sir Charles Lyell's Supplement for

corroboration of the foregoing statements.

[xxiv PREFACE.]

the completeness of which is marked by the very difficulty of

finding, amid so much new and redundant life, a single identical

specific variety, than the well-known existence of the Terebratula in

the earliest, as well as in the existing seas, can efface the great

ground-plan of successive geolo gical eras.1 Nor does it

explain the matter to say that

geographical changes took place, bringing with them the denizens of

different

climates, and adapted for different modes of life. The same Almighty

Power

which now provides habitats and conditions suitable for the

wants

of his creatures, would doubtless have done so during all the past.

Geographical

changes are at all times indissolubly connected with changes in the

conditions

of being; and they serve, in so far, to explain the rule in

the stated

order of geological events, when a due proportion of extinct and of

novel

forms are found co-existent. But how can they explain the exception? A

singular effect must have a singular cause. And when we find that there

were changes relating to the world's inhabitants altogether singular

and abnormal in

their revolutionary character, we must infer that the medial causes of

which

the Creator made use were of a singular and abnormal character also. On

this head the best-informed ought to speak with extreme diffidence. We

can

but imagine that there may have been a long, immeasurable period during

which a subsidence, so to speak, took place in the creative energy, and

during

which all specific forms, one after another, died out, — the lull of a

dying

creation, — and then a renewal of the impulsive force from that Divine

Spirit

which brooded over the face of the earliest chaotic

1 See Terebratula, in Appendix. The

extinct Terebratula is now called Rhynconella.

[PREFACE. xxv]

deep, producing geographical changes, more or less rapid, which should

prepare the way for the next stage in our planetary existence, — its

new framework, and its fresh burden of vital beings.

The other great break in the continuity of fossils, which occurs between the Chalk and the Tertiary, seems to be very much in the same condition with that of which we have just spoken. New connecting genera have been discovered, but still not a single identical species. Jukes, in his Manual published at the end of last year, says, — ' Near Maestricht, in Holland, the chalk, with flint, is covered by a kind of chalky rock, with grey flints, over which are loose yellowish limestones, sometimes almost made up of fossils.' Similar beds also occur at Saxoe in Denmark. Together with true cretaceous fossils, such as pecten and quadricostatus, these beds contain species of the genera Voluta, Fasciolaria, Cyprea, Oliva, etc. etc., several of which GENERA are only found elsewhere in the Tertiary rocks.1

Sir Roderick Murchison's late explorations in the Highlands, — although, of course, local in their character, have made a considerable change in the GEOLOGY OF SCOTLAND. The next edition of the Old Red Sandstone will be the most fitting place to speak of these at length; and I have some reason to believe that Sir Roderick himself will then favour me with a communication giving some account of them. Suffice it at present to say, that the supposed Old Red Conglomerate of the Western Highlands, as laid down in the year 1827 by Sir Roderick himself; accompanied by Professor Sedgwick, and so far acquiesced in by my husband,

1 A doubt has nevertheless been expressed

whether these are not broken-up Tertiaries.

[xxvi PREFACE.]

although he always wrote doubtfully on the subject, has now been

ascertained to be, not Old Red, but Silurian. In Sir Roderick's last

Address to the British Association, he says, — 'Professor Sedgwick and

himself had thirty-one years ago ascertained an ascending order from

gneiss, covered by quartz

rocks, with limestone, into overlying quartzose, micaceous, and other

crystalline rocks, some of which have a gneissose character. They had

also observed what they supposed to be an associated formation of red

grit and sandstone; but the exact relations of this to the crystalline

rocks was not ascertained, owing to bad weather. In the meantime, they,

as well as all subsequent geologists, had erred in believing the

great and lofty masses of purple and red conglomerate of the western

coast were of the same age as those on the east, and therefore 'Old Red

Sandstone.' . . . 'Professor Nicol had suggested that the quartzites

and limestones might be the equivalent of

the Carboniferous system of the south of Scotland. Wholly dissenting

from

that hypothesis, he (Sir Roderick) had urged Mr. Peach to avail himself

of his first leisure moments to re-examine the fossil-beds of Durness

and

Assynt, and the result was the discovery of so many forms of undoubted

Lower

Silurian characters (determined by Mr. Salter), that the question has

been

completely set at rest, there being now no less than nineteen or twenty

species of M'Lurea, Murchisonia, Cephalita, and Orthoceras, with an

Orthis,

etc., of which ten or eleven occur in the Lower Silurian rocks of North

America.'

This change would demand an entirely new map of the Geology of

Scotland; for there is clearly ascertained to be an ascending series

from west to east, beginning with an

[PREFACE. xxvii]

older or primitive gneiss, on which a Cambrian conglomerate, and

over that again a band containing the Silurian fossils, rest; while a

younger gneiss occupies a portion of the central nucleus, having the

Old Red Sandstone series on the eastern side. A change has likewise

been made in the internal arrangements of the Old Red, of which the

next edition of my husband's

work on the subject will be the proper place to speak in detail. In the

meantime, I may just mention, that the Caithness and Cromarty beds have

been found to occupy, not the lowest, but the central place, the lowest

being

assigned to the Forfarshire beds, containing Cephalaspis, associated

with

Pteraspis, an organism characteristically Silurian. That which bears

most

upon the subject before us is the now perfectly ascertained imprint of

the

footsteps of large reptiles in the Elgin or uppermost formation of the

Old

Red. A shade of doubt had rested upon the discovery made many years ago

by

Mr. Patrick Duff of the Telerpeton Elginense, not as to the

real nature

of the fossil, which is indisputably a small lizard, but as to whether

the

stratum in which it was found belonged to the Old Red, or to the

formation

immediately above it. It will be observed, however, that the existence

of

reptiles in the Old Red did not rest altogether upon this, because the

foot

prints of large animals of the same class had been ascertained in the

United

States of America. I cannot but conceive, therefore, that Mr. Duff, in

a

recent letter or paper read in Elgin, and published in the Elgin

and

Morayshire Courier, makes too much of the recent discoveries in

his

neighbourhood, when he asserts that the Old Red Sand stone has been

hitherto

considered exclusively fish formation, and that the appearance

of

reptiles is altogether novel.

[xxviii PREFACE.]

'Now,' says he, 'that the Old Red Sandstones of Moray have acquired

some celebrity, it may not be unprofitable to trace the different

stages by which the discovery was arrived at of reptilian remains in

that very ancient system, which till now was held to have been

peopled by no higher order of beings than fishes.' Mr. Duff

forgets that in the programme, as it may be

called ,given by my husband, of the introduction of different types of

animal life, as ascertained in his day, reptiles are made to occupy

precisely

the position they do now. To refresh the memory of the reader, I shall

here reproduce it, as given in the Testimony of the Rocks. At

page

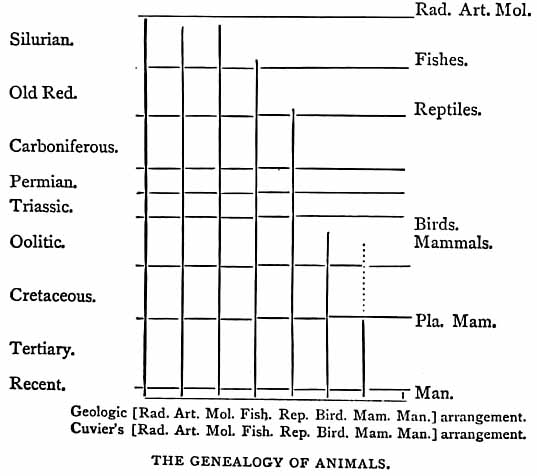

14 is this diagram

And immediately following it occurs this comment: — 'In the

many-folded pages of the Old Red Sandstone, till we

[PREFACE. xxix]

reach the highest and last; there occur the remains of no

other vertebrates than those of this fourth class [fishes]; but in its

uppermost deposits there appear traces of the third or reptilian class;

and in passing upwards still, through the Carboniferous, Permian, and

Triassic systems, we find reptiles continuing the master-existences of

the time.' At pages 16, 17, express allusion is made to the Telerpeton

Elginense, with the doubt as to the nature of its locale very

slightly touched upon.1

All this Mr. Duff has forgotten, apparently; and it appears likewise

not

to have come within his cognizance that Sir Charles Lyell distinctly

recognises his Telerpeton as well as the American foot prints, and

assigns both their proper places, in the last edition of his Principles.

Even in the edition before the last of the Siluria, almost

the first thing that meets us, on opening it at Chapter Tenth, which

treats of the Old Red Sandstone, is a print of the fossil skeleton of

this same Telerpeton

Elginense, — its true place assigned to it with quite as much

certainty

as now! These very singlar lapses in memory seem not to be peculiar to

Mr.

Duff. I have seen it stated in an anonymous article published in a

widely

circulated journal,2 and in connexion with the discovery of

the

Elgin reptile foot-prints, that Hugh Miller considered the Old Red

Sandstone

1 This doubt, I see by Sir Roderick Murchison's latest

Address to the British Association, is not yet entirely obviated. See

Appendix.

2 For this article, as an excellent specimen

of its class, see Appendix, under the head 'Recent Geological

Discoveries;' and, in contradistinction to it, the extract from Sir R.

Murchison's Address ought to be carefully studied. I myself had seen

neither that extract nor the recent Siluria until after this

short sketch was in type; the references to the latter having been

introduced afterwards; and it may be conceived with what feelings of

gratification I have perused Sir Roderick's repeated assurances of

adherence to the 'Old Light.'

[xxx PREFACE.]

to have been a shoreless ocean without a tree! — utterly ignoring

the fact that he was himself the discoverer of the first Old Red

fossil-wood of a coniferous character, and that he thence expressly

infers the then

existence of vegetation of a high order. Is it not enough to add to the

store

of knowledge without attempting to undermine all that has gone before?

Must

the discovery of an additional reptile, a few additional marsupials, be

the

signal for the immediate outcry, 'All is changed; the former things

have

passed away; all things have become new'? My husband was solicitous

even

to the point of nervous anxiety to exclude from his writings every

particle

of error, whether of facts or of the conclusions to be drawn from them.

Much

rather would he never have written at all than feel himself in any

degree

a false teacher. 'Truth first, come what may afterwards,' was his

invariable

motto. In the same spirit, God enabling me, I have been desirous to

carry

on the publication of his posthumous writings. God forbid that one

intrusted

with such sacred guardianship should seek to pervert or suppress a

single

truth, actual or presumptive, even though its evidence were to

overthrow

in a single hour all his much-loved speculations, — all his reasonings,

so

long cogitated, so conscientiously wrought out. Yet I must confess that

I

was at first startled and alarmed by rumours of changes and discoveries

which,

I was told, were to overturn at once the science of Geology as hitherto

received,

and all the evidences which had been drawn from it in favour of

revealed

religion. Though well persuaded that at all times, and by the most

unexpected

methods, the Most High is able to assert Himself, the proneness of man

to

make use of every unoccupied position in order to maintain

[PREFACE. xxxi]

his independence of his Maker seemed about to gain new vigour by acquiring a fresh vantage-ground. The old cry of the eternity of matter, and the 'all things remain as they were from the beginning until now,' rung in my ears. God with us, in the world of science henceforth to be no more! The very evidences of His being seemed about to be removed into a more distant and dimmer region, and a dreary swamp of infidelity spread onwards and backwards throughout the past eternity.

Without stopping to inquire whether, although the science of Geology

had been revolutionized, those fears were not altogether

exaggerated, it is enough at present to know, that as Geology has not

been revolutionized, there is no need to entertain the question. I

trust I have at least succeeded in furnishing the reader with such

references, — few and simple when we once know where to find them, — as

may enable him to decide upon this important matter for himself. If I

have learned anything in the course of the investigations which I have

been endeavouring to make, it is to take nothing upon credence, but to

wait patiently for all the evidence which can be brought to bear upon

the subject before me; and this, I believe, is the only way to make any

approximation to a correct opinion. In truth, the science of Geology is

itself in that condition, that no fact ought to be accepted as a basis

for

reasoning of a solid kind, until it has run the round of investigation

by

the most competent authorities, and has stood the test of time. It is

peculiarly

subject to the cry of lo, here! and lo, there! from false and

imperfectly

informed teachers; and I believe the men most thoroughly to be relied

on

are those who are the slowest to theorize, the last to form a judgment,

and

[xxxii PREFACE.]

who require the largest amount of evidence before that judgment is finally pronounced.

In addition to the inspection of my ever kind and generous friend Mr. Symonds,1 I have submitted the following pages to the reading of Mr. Geikie2 of the Geological Survey, who has here and there furnished a note. Of the amount and correctness of his knowledge, acquired chiefly in the field and in the course of his professional duties, my husband had formed the highest opinion. Indeed, I believe he looked upon him as the individual who would most probably be his successor as an exponent of Scottish Geology. One who walks on an average twenty miles per day, and who has submitted nearly every rood of the soil to the accurate inspection demanded by the Survey, must be one whose opinion, in all that pertains to Scottish Geology in especial, must be well worth the having. I have to add an expression of most grateful thanks to Sir Roderick Murchison, for his prompt attention to sundry applications which I was constrained to make to him. His letters have been of the utmost importance in enabling me to perceive clearly the alterations which have taken place in our Scottish Geology, and the reasons for them. One feels instantaneously the benefit of contact with a master-mind. A few sentences, a few strokes of the pen, throw more light on the subject than volumes from an inferior hand.

It remains now only to explain that this course of Lectures, as delivered before the Philosophical Institution, consisted

1The Rev. W. S. Symonds, author of Old Stones, Stones of the Valley, etc., and the compiler of the index to the recent edition of Sir R. Murchison's Siluria.

2 Archibald Geikie, Esq., author of The

Story of a Boulder.

[PREFACE. xxxiii]

of eight, instead of six. Those now published are complete, according to their limits, in all that relates to the facts, literal or picturesque, of the subject; and the last two of the series will be found in The Testimony of the Rocks, under the heads of 'Geology in its Bearing on the Two Theologies,' and 'The Mosaic Vision of Creation.' If it had been within the contemplation of the author to publish the six Lectures as they now stand, these last two would have formed their natural climax or peroration. And, accordingly, I entertained some thought of republishing them here, in order that the reader might enjoy the advantage of having the whole under his eye at once. But as they are not in any way necessary to the completion of the sense, and perhaps Geology, viewed simply by itself; and in the light of a popular study, is as well freed from extraneous matter, it was thought best, on the whole, to refer the reader who wishes to see the eight discourses in their original connexion, to The Testimony of the Rocks.

I have, instead, added an Appendix of rather a novel character. In

addition to the Cruise of the Betsey, and Ten Thousand

Miles over the

Fossiliferous Deposits of Scotland, there was left a volume of

papers unpublished as a whole, entitled A Tour through the Northern

Counties of Scotland. They had, however, been largely drawn upon

in various other works; but, scattered throughout, were passages of

more or less value which I had not met with elsewhere; and some such,

of the descriptive kind, I

have culled and arranged as an Appendix; first, because I was loath

that

any original observation from that mind which should never think again

for

the instruction of others should be lost, and also because many of

those

passages were of a kind which

[xxxiv PREFACE.]

might prove suggestive to the student, and assist him in reasoning

upon those phenomena of ordinary occurrences without close observation

of which no one can ever arrive at a successful interpretation of

nature. If the reader should descry aught of repetition which has

escaped my notice, I

must crave his indulgence, in consideration of the very diffi cult and

arduous task which God, in His mysterious providence, has allotted me.

To endeavour to do by these writings as my husband himself would if he

were yet with

us — to preserve the integrity of the text, and in dealing with what is

new, to bring to bear upon it the same unswerving rectitude of purpose

in

valuing and accepting every iota of truth, whether it can be explained

or

not, rejecting all that is crude, and abhorring all that is false, —

this

has been my aim, although, alas! too conscious throughout of the

comparative

feebleness of the powers brought to bear upon it. If; however, the

reader

is led to inquire for himself; I trust he will find that these powers,

such

as they are, have been used in no light or frivolous spirit, but with a

deep and somewhat of an adequate, sense of the vast importance of

the

subject,

_________________________