[31]

CHAPTER III.

DENUDATION, SYNCLINAL AND ANTICLINAL CURVES, UNCONFORMABLE STRATIFICATION, AND WASTE PRODUCED BY

CHEMICAL ACTION.

I MUST now more precisely explain the meaning of a few terms which I have already employed,

and shall have occasion to use very frequently.

Denudation, in the geological sense of the word, means the stripping away of rocks from the

surface, so as to expose other rocks that lay concealed beneath them.

Running water wears away the ground over which it passes, and carries away detrital matter,

such as pebbles, sand, and mud; and if this goes on long enough over large areas, there is no

reason why any amount of matter should not in time be removed. For instance, we have a notable

case in North America of a considerable result from denudation, now being effected by the river

Niagara, where, below the Falls, the river has cut a deep channel through the rocks, about seven

miles in length. The proofs are perfect that the Falls originally began at the great, escarpment

at the lower end of what is now this gorge; that the river, falling over this ancient cliff, by

degrees wore for itself a channel backwards, from two hundred to a hundred and sixty feet deep,

through strata that on either side of the gorge once formed a continuous plateau.

[32 Denudation.]

I merely give this instance to show what I mean by denudation produced by running water. At

one time the channel did not exist. The river has cut it out, and in doing so, strata—some of them

formerly one hundred and sixty feet beneath the surface—have been exposed by denudation.

Possible, but very uncertain calculations, show that to form this gorge a period at the least of

something like thirty-five thousand years has been required. This is an important instance, and

it is similar to many other cases constantly before our eyes, on a smaller scale, which rarely

strike the ordinary observer.

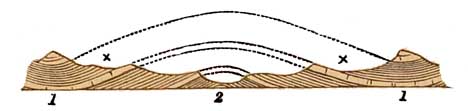

Refer to fig. 6, and suppose that we have different strata, 1, 2, 3, and 4, lying horizontally one

above the other, together forming a mass several hundreds of feet in thickness. The running

water of a brook

FIG. 6.

or river by degrees wore away the rocks more in one place than another, so that the strata 3, 2,

and 1, were successively cut into and exposed at the surface, and a valley in time is formed. This

is the result of denudation.

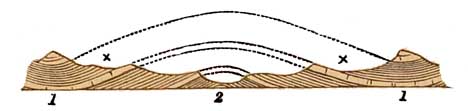

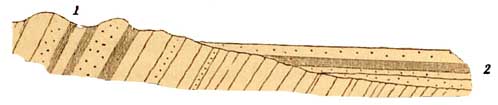

Or to take a much larger instance. The strata that form the outer part of the crust of the Earth

have, in many places, by the contraction of that crust due to

cooling of the mass, been thrown into anticlinal and

synclinal curves. A synclinal curve means that the

curved strata are bent downwards as in 1, Fig. 7, an anticlinal curve that they bend upwards as

in 2. The whole were originally deposited horizontally,

[Denudation. 33]

consolidated into rock, and afterwards bent and contorted. The strata marked x may perfectly

correspond in all respects in their structure and fossils, and in hundreds

FIG. 7.

1. Synclinal curves. 2. Anticlinal curve,

1. Synclinal curves. 2. Anticlinal curve,

of similar cases it is certain that they were once joined as horizontal strata, and afterwards

thrown into anticlinal and synclinal curves. The strata indicated by dotted lines (and all above)

have been. removed by denudation, and the present surface is the result.

Chemical action is another agent that promotes waste or denudation. Thus rain water, always

charged with carbonic acid, falling on limestone rocks such as the Carboniferous Limestone, or

the Chalk, not only wears away part of these rocks by mechanical action, but also dissolves the

carbonate of lime and carries it off in solution as a bicarbonate. This fact is often proved by

numbers of unworn flints sometimes several feet in thickness scattered on the surface of the

table-land of chalk in Wilts and Dorsetshire. The flints now lying loose on the surface once

formed interrupted beds often separated by many feet of chalk. The chalk has been dissolved and

carried away in solution chiefly by moving water, and the insoluble flints remain.

Degradation of the rocks of many regions is also powerfully affected by occasional landslips. The

waste thus produced is seen on a large scale in many of the Yorkshire valleys, where

Carboniferous sandstones and shales are jnterstratified, and vast shattered ruins of

[34 Denudation.]

sandstones cumber the sides of the hills and the bottoms of the valleys in wild confusion (fig.

66, p. 329). In Switzerland the relics of old landslips are often seen on a magnificent scale; and

some of these, such as those of the Rossberg, and St. Nicholas in the valley of Zermatt, have

taken place in the memory of living men.

The constant atmospheric disintegration

of cliffs, and the beating of the waves on the shore, often aided by landslips,

is another mode by which watery action denudes and cuts back rocks. This

has been already mentioned. Caverns, bays, and other indentations of the

coast, needle-shaped rocks standing out in the sea from the main mass of a

cliff, are all caused or aided by the long-continued wasting power of the

sea, which first helps to destroy the land and then spreads the ruins in

new strata over its bottom.

It requires a long process

of geological education to enable anyone thoroughly to realise the conception

of the vast amount of old denudations; but when we consider that, over and

over again, strata thousands of square miles in extent, and thousands of

feet in thickness, have been formed by the waste of older rocks, equal in

extent and bulk to the strata formed by their waste, we begin to get an idea

of the greatness of this power. The mind is then more likely to realise the

vast amount of matter that has been swept away from the surface of any country,

in times comparatively quite recent, before it has assumed its present form.

Without much forestalling the subject of a subsequent chapter, I may now

state that a notable example on a grand scale may be seen in the coal-fields

of South Wales, of Bristol, and of the Forest of Dean. These three coalfields

were once united, but those of South Wales and Dean Forest are now about

twenty-five miles

[Unconformity. 35]

apart, while the Bristol and Somersetshire coal-field is separated from both by the estuary of

the Severn. These separations have been brought about by the agency of long-continued

denudations, which have swept away thousands of feet of strata bent into anticlinal and synclinal

curves in the manner shown at x in fig. 7, p. 33, and fig. 115, p. 601. The coal-field of the

Forest of Dean has thus become an outlier of the great South Wales coal-field; and the Bristol or

Somersetshire coal-field forms another outlier of a great area, of which even the South Wales

coal-field is a mere fragment. Such denudations have been common over large areas in Wales

and the adjacent counties, and in many another county besides.

Observation and argument alike tell us that we need have no hesitation in applying this

reasoning to all hilly regions, whether formed of stratified rocks alone or intercalated with

igneous rocks, and thus we come to the conclusion that the greater portion of the rocky masses

of our island have been arranged and re-arranged under slow processes of the denudation of old,

and the reconstruction of newer strata, extending over periods that seem to our finite minds

almost to stretch into infinity.

Unconformable stratification, when its significance has been realised by the student, cannot fail

at once to impress on the mind a sense of the degradation of strata in some old epoch similar to

that which is now going on, and I know of few objects that speak more eloquently of geological

time.

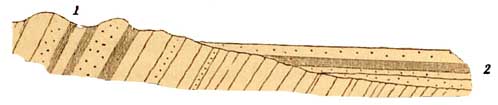

In the following diagram No. 1 represents an old land surface, in which perhaps beds of

sandstone and slate or shale have been upheaved at a high angle. Let us then suppose that, by the

wasting power of weather and

[36 Unconformity.]

the sea, the strata No. 2 have been won from that old land and deposited on the upturned and

denuded edges of the strata No. 1. This constitutes a case of unconformable stratification, and this alone marks the lapse

FIG. 8.

1. Old disturbed strata.

2. Later beds lying unconformably upon them.

of immense periods of geological time, first by the deposition, consolidation, and upheaval of the

strata No. 1, and secondly in the deposition of the strata No. 2, which were made from the waste

of No. 1.

There are many cases of this kind of unconformity extending through all geological time from

the Laurentian epochs onwards. If, in addition to this, we consider the meaning of the

progressive changes of genera and species of animals and plants, as we proceed from the older to

the newer formations (as expressed in Chapter II.), it soon becomes obvious, that as yet we

have no means of even attempting to form any clear idea of the time that has elapsed since life

first appeared on the surface of the world, whether we adopt the original view of a distinct

creative act for each individual species, or prefer the later one of evolution and progressive

development.

To explain in some detail the anatomical structure or existing Physical Geography of our island,

as dependent on the nature of its strata and the alterations and denudations they have undergone

is the main object of this book. In making this attempt I shall

[Object of Book. 37]

first describe in some detail and in chronological order all the rocky formations that constitute

Great Britain, with reference, where it can be done, to the Physical Geology and Geography of

each large special epoch, for only in this way may we hope to get an idea of how our island at

length got into that phase of its history in which we happen to live. If the reader has been able to

follow me in what I have already written, I think he will understand what I shall have to say in

the remaining chapters.