CHAPTER VI.

ARENIG, LLANDEILO, AND BALA BEDS.

The Arenig Beds succeed the Tremadoc slates at St. David's in South Wales, and in North Wales

they also overlie the Tremadoc slates between Towyn and the neighbourhoods of Dolgelli,

Ffestiniog, Tremadoc, and Criccieth in Caernarvonshire, north of which they also occur in part

of the country between Caernarvon and Bangor. They were first distinguished by Professor

Sedgwick, and named Arenig slates, and afterwards termed lower Llandeilo beds by Sir Roderick

Murchison, who had previously included them as part of the Llandeilo flags in his descriptions

and sections of the Lower Silurian rocks that lie west of the Stiper Stones near Shelve, in

Shropshire.

In the large district of Merionethshire the Arenig slates appear at the base of the great volcanic

series of felspathic lavas and ashes, of which the mountains of Cader Idris, Aran Mowddwy,

Arenig, and the Moelwyns form distinguished features in the landscape. They are in these

districts never more than about 800 feet in thickness, and the Arenig beds of Merionethshire,

at their base invariably consist of beds of grit, sometimes conglomeratic. The higher strata of

this sub-formation are generally slaty. For reasons that will afterwards appear, I believe that

the Arenig strata, on a

[70 Arenig Slates.]

large scale, rest unconformably on the underlying rocks of North Wales.

In Cumberland the Arenig slates form the mountains of Skiddaw and Saddleback, and from the

borders of the Old Red Sandstone, a few miles further east, they stretch right across the country

westward to Egremont and northward to Sunderland, south of which town, near Cockermouth,

they are directly overlaid by the Carboniferous Limestone. In that country they have usually

been called the Skiddaw slates. In Scotland the Durness strata belong to the same rocks.

In Britain the fossils that belong to this part of the Silurian series are not very numerous,

taken as a whole, though some groups are remarkably abundant. As far as observation has gone,

Hydrozoa of the sub-class Graptolitidæ first appear in these strata, including some 20 genera

and 48 species. The greatest number of species belong to the genus Didymograptus, of which

20 species have been named, after which come Tetragraptus, Diplograptus, Dichograptus, and

Dendrograptus.

Eighteen genera and 47 species of Trilobites occur in the same rocks, including Agnostus (A.

hirundo, &c.); Asaphus (A. Homfrayi, &c.); Ogygia (O. Selwynii, &c); Trinucleus (T.

Ramsayi, &c.); Calymene (C. parvifrons, &c.), and many others. Of Brachiopoda there are 7

genera and 18 species including three Lingulas, Lingulella Davisii and L. lepis, 7 species of

Orthis, including O. calligramma and O. lenticutaris; 2 species of Obolella; 2 of Discina, and

others Of Lamellibranchiata there are only 5 genera and 8 species known, including Modiolopsis trapeziœformis, Palæarca socialis, and P. amygdalus, Ctenodonta elongata, &c., and

Redonia Anglica. Pteropoda of

[Llandeilo and Caradoc Beds, 71]

the genera Theca and Conularia are found, and 6 species of Bellerophon, and of Cephalopoda

there are 5 species of Orthoceras. Of univalve shells we have only 3 species—Pleurotomaria

Llanvernensis, Ophileta, and Raphistoma, and several other fossils needless to enumerate.

In all, 184 species are known at present in the Arenig beds, mostly characteristic of these

strata, for only about 8 per cent. pass upward into this horizon from the Tremadoc beds, a

proportion of which go down into the Lingula flags, and about 7 per cent. pass upward into the Llandeilo flags.

Though in Wales the base of the Arenig beds is clear, it seems as yet impossible to draw any

definite physical boundary between the Arenig beds and the overlying Llandeilo slates, for there

is nothing like unconformity, and no marked lithological difference in the passage from one to

the other. We have already seen that there is a very limited passage of species from the Arenig

slates into those of the so-called Llandeilo series.1

Just about this time an important episode took place in the history of the Llandeilo and Bala beds

over large tracts of Wales and Cumberland, for a series of volcanic eruptions occurred on a

great scale while the strata were being deposited (fig. 62, p. 322). To this subject I shall by-and-by return.

In North Wales the Llandeilo and Baja or Caradoc beds combined, attain a thickness of from

4,000 to 6,000 feet, consisting chiefly of slaty rocks, sometimes interstratified with grits and

occasional bands of limestone, of which the Bala Limestone is the most conspicuous. The whole

series ranges right round the mountains of

1 The Llandeilo flags of North Wales are very unlike those of Llandeilo, which are generally called

upper Llandeilo beds.

[72 Llandeilo and Caradoc Beds.]

Cader Idris, Aran Mowddwy, Arenig, and the Moelwyns, resting on the lava beds and ashes, and

overlaid on the east by Upper Silurian strata, fig. 57, p. 304. They also form, with igneous

rocks, the larger part of the Berwyn mountains, and with the Arenig slates the whole of the

ground between the Stiper Stones and the Upper Silurian rocks of Chirbury and Montgomery,

fig. 13, p. 59. The typical Caradoc Sandstone, crossing the strike, ranges between Church

Stretton and Caer Caradoc, from whence it stretches in a broad band northward towards the

Wrekin, and southward to Corston. The greater part of South Wales is formed of slates and grits

of Llandeilo and Caradoc age, lying west and north of the Upper Silurian and Old Red Sandstone

strata, and the same formations, associated with volcanic rocks, rise like an island surrounded

by Upper Silurian strata, in the country between Builth and Llandegley in Radnorshire.

In South Wales, where they were first described by Murchison, the Llandeilo beds consist of

sandy calcareous flags, black slaty rocks, and beds of grit and sandstone. A few beds of limestone

occur in them in Carmarthenshire, at Llandeilo, and in Pembrokeshire near Narberth; and the

Bala limestone is found higher in the series in the Caradoc or Bala beds of Merionethshire. They

are often highly fossiliferous. There is a much larger development of fossils in the Llandeilo

flags than in the pre-existing Silurian strata. The Trilobites of the Llandeilo beds are mostly

peculiar to it, and the genera Æglina, Barrandia, and Ogygia are very common, Ogygia Buchii

being especially characteristic. Viewed as a whole, however, the Llandeilo beds, as already

stated, pass insensibly into, and have many genera and species in common with the Caradoc

[Llandeilo and Caradoc Fossils. 73]

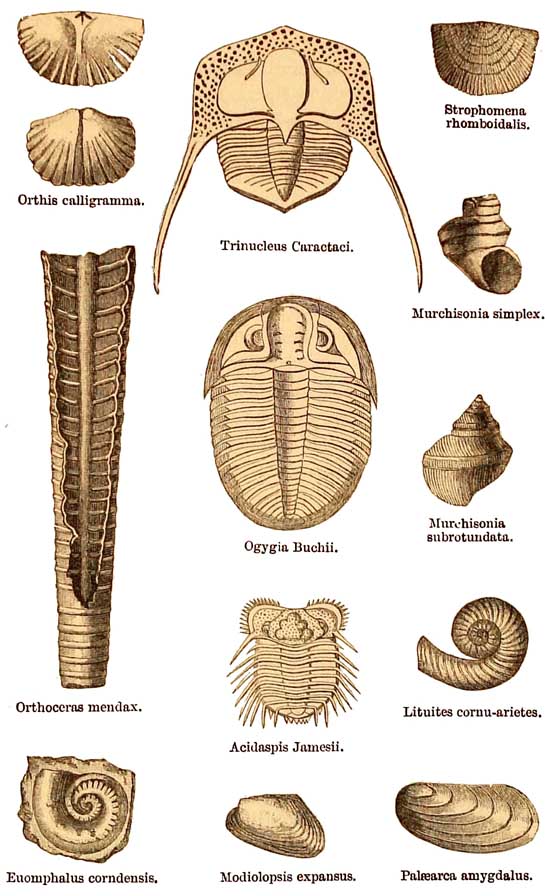

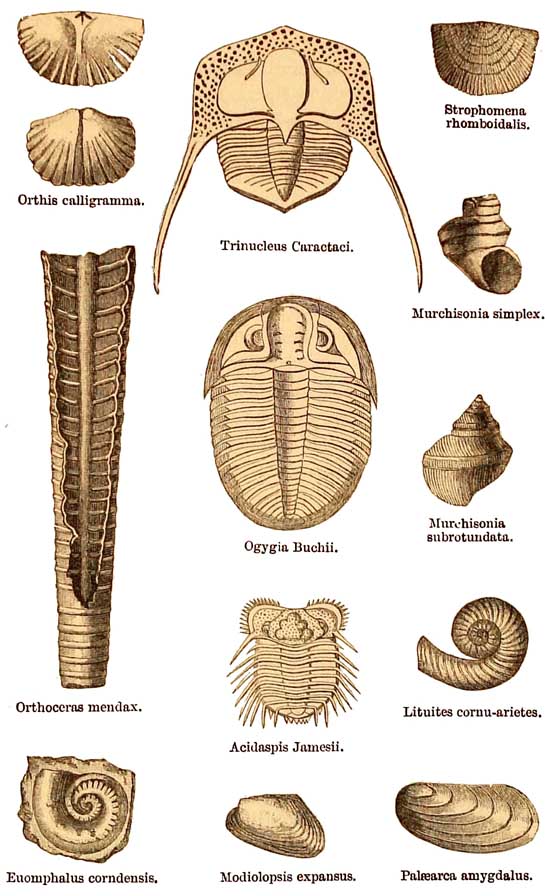

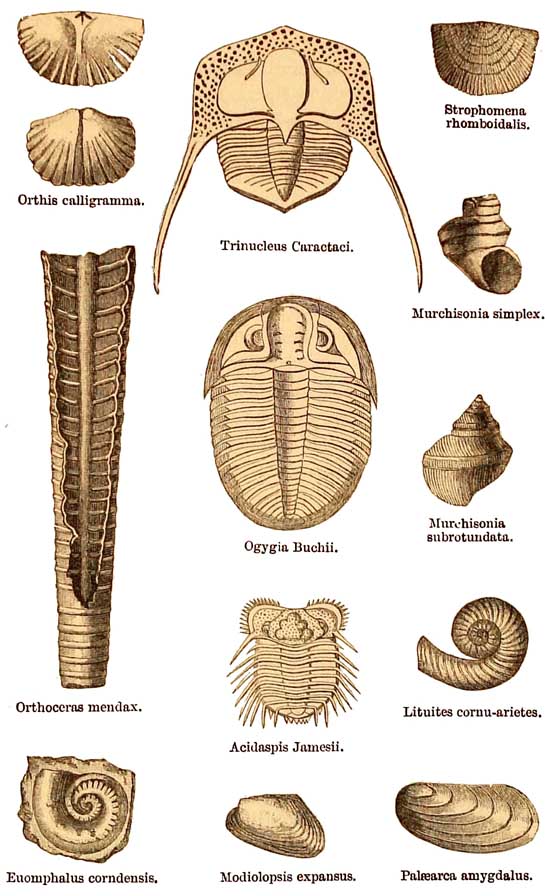

FIG. 18.

Group of Llandeilo flag and Caradoc or Bala Fossils.

[74 Llandeilo and Caradoc Beds.]

Sandstone or Bala beds. 19 genera and 34 species of orals have been described in these lower

Silurian strata, among which Heliolites and Petraia are perhaps the most common.

Fragments of Echinodermata are common, including Cystideans, common in the Bala Limestone,

and one star-fish, Palœaster Caractaci. In all, more than 40 genera and 200 species of

Trilobites have been described from the whole series of Lower Silurian British rocks, among

the chief of which are species of Olenus, Agnostus, Ampyx, Lichas, Ogygia, Acidaspis, Asaphus,

Harpes, Illœnus, Phacops, and Trinucleus (T. Caractaci). In the Caradoc beds alone, 23 genera

and 111 species are known. Of bivalve shells there are 22 genera and 171 species of

Brachiopoda, the most common of which belong to the genera Strophomena, Leptœna, Lingula,

Orthis, and Rhynchonella.

Of the Lamellibranchiate molluscs

there are 17 genera and 87 species known at present, prominent among which

are Ctenodonta, Modiolopsis, Pterinœa, Palœarca, and Ambortychia. Of Pteropoda

there are known 6 genera and 31 species, of which Theca is most abundant;

16 genera and 66 species of Gasteropoda, the most characteristic of which

in point of numbers are Euomphalus (10), Murchisonia (15), Pleurotomaria, Cyclortema, and Holopœa. Of Nucleobranchiata, Bellerophon (14). Of the

Cephalopoda there are 10 genera and 62 species—Cyrtoceras (5), Lituites (6),

Orthoceras (42), Phragmoceras (1), and others. No fishes nor any other vertebrate

animals have yet been found in the Lower Silurian rocks of Wales or elsewhere.

In Cumberland the Coniston Limestone is believed to be the equivalent of the Bala Limestone of

North

[Igneous Rocks. 75]

Wales, and the assemblage of fossils in each is very nearly the same.

I have already mentioned the occurrence of an important episode characterised by volcanic

eruptions, during the accumulation of the Lower Silurian strata in Wales. The proof of this is

that in Carnarvonshire and Merionethshire extensive interstratified sheets of felspathic lavas

and ashes are associated with the Silurian rocks on two horizons, the lower that of the Llandeilo

beds, and the higher in the Caradoc series. I do not, however, wish to imply that between them

there was a complete cessation of volcanic activity, but simply that in what is now the region of

North Wales, there was for a time an interval of comparative repose.

If any one will examine the Geological Survey maps of North Wales, he will observe that

opposite Barmouth, beginning with the hills on the south side of the estuary of the Mawddach, a

great series of igneous rocks sweep round the country in a crescent form, including the

mountains of Cader Idris, Aran Mowddwy, the Arenigs, and lastly the Moelwyns, the high

southern escarpments of which overlook from the north the beautiful vale of Ffestiniog. These

consist of felspathic lavas, and interstratified ashes or tufas, the whole being also associated

with bands of Silurian slate, which are sometimes found to be fossiliferous, especially when

bedding and cleavage coincide. Among these volcanic rocks, but especially in the Arenig,

Tremadoc, and Lingula beds below them, there are numerous lines and bosses of greenstones

(diorites, &c.), and also of more purely felspathic traps, which are not interbedded but

distinctly intrusive. These I have elsewhere shown give evidence of the underground working of

the

[76 Igneous Rocks.]

melted matter, the eruption

of which to the surface through volcanic rents, produced the lavaflows and

ashes already mentioned. The ashy beds are sometimes coarse and tufaceous,

but were also often formed of fine volcanic dust, which being now consolidated

into hard felspathic rocks, are at first sight somewhat difficult to distinguish

from the associated lavas. Practice, however, renders it comparatively easy,

and in distinguishing the difference, the observer is aided by the circumstance,

that underneath each lava current the slates, once beds of mud, are apt to

be baked and porcellanised at the point of junction with the originally hot

lavas, which having in the meanwhile cooled, the slaty beds that rest on

them are in that respect unaltered.

The second series of eruptions

may be traced as follows. Near Bala, not far below the limestone, there are

a few thin bands of volcanic ashes. These, as we go northward to the rivers

Machno, Lledr, and Conwy, gradually thicken, and by-and-by get mingled in

that slaty area with numerous thin and thick bands of felspathic lavas, the

importance of which as large masses, culminates in Snowdon and the surrounding

area, going northward by Glyder-fawr, Glyder-fach, Carnedd Dafydd, and Carnedd

Llewelyn, and so on to Conway. South of Snowdon the same kinds of lavas and

ashes are seen in force on the sides of Moel Hebog, and the great mass of Llwyd-mawr near Dolbenmaen.

Other large bosses of intrusive rocks, mostly felspathic, occur on Y-Foel-frâs, between

Snowdon and Conway, another between Llanllyfni and Bethesda, a third near the eastern shore of

Menai Straits, and many more including the beautiful mountains of Yr Eifl, or The Rivals, in the

north horn of Cardigan Bay,

[Unconformity. 77]

known as the district of Lleyn. These, ere exposure by denudation, probably were the roots of

the volcanos, or in other words the deep-seated centres from whence the explosive force of

steam drove out the lavas and showers of ashes, which, during successive eruptions, with minor

periods of repose, got interstratified with the mud and sand beds that were deposited in the sea

of the Llandeilo and Bala or Caradoc period.

On a smaller scale similar volcanic rocks are interstratified with the Llandeilo and Bala beds of

the Berwyn Hills, also of the Breidden Hills, and the hills west of the Longmynd and Stiper

Stones towards Chirbury and Church Stoke, of the country between Builth and Llandegley in

Radnorshire, and in North Pembrokeshire from the ground round St. David's, extending for

many miles to the east, by Mathry, Fishguard, St. Dogmells and Mynydd Preselley.

The next question that occurs to me is, what was the nature of the physical geography of this

area during the deposition of the Arenig slates, and also at a later epoch when the Llandeilo and

Caradoc or Bala beds were being deposited.

With regard to the Arenig slates in Pembrokeshire and Merionethshire, I know of no signs of

unconformity, that is to say, of a lapse of time unrepresented by the deposition of marine strata

either in Pembrokeshire or in Merionethshire, unless there be some symptoms of it in the

latter county. But when we go further north into Carnarvonshire, the case is different. There,

at the widening of the Passes of Llanberis and Nant Ffrancon, the Lingula flags are not more than

2,000 feet thick, whereas further south, between Ffestiniog and Portmadoc, they are at least

4,000 feet in thickness. Furthermore, in those valleys in Caernarvonshire

[78 Physical]

there is, as yet, no certainty of the existence of the Tremadoc slates, and these ought to

be found overlying the Lingula flags if the whole of the Silurian series were present. Still

further, as we approach Caernarvon and Bangor, even the Lingula flags are absent, and the

Arenig slates are found lying directly on the purple slates and conglomerates of the Cambrian

series all the way from Bangor to Caernarvon. This clearly shows that the base of the Arenig

slates has overlapped the whole of the Tremadoc slates and Lingula flags, in the area between the

Ffestiniog and Portmadoc country and the neighbourhood of the Menai Straits, and an overlap so

great means unconformity between the strata; or, in other words, in this area the strata of

older date than the Arenig slates had been raised above the sea, and subjected to sub-aerial

agencies of denudation, while the deposition of the Arenig slates was going on elsewhere. In this

manner, therefore, it happens that the Arenig slates are now found resting directly on the

Cambrian strata, without the intervention of the missing members of the series, viz., the

Tremadoc slates and Lingula flags; and still further north, in Anglesea, these strata are also

wanting.

The effect of this episode in the physical geography of the area seems to have been, that at this

period a tract of land lay in the north-west of what is now Wales, and probably far beyond that

district during the deposition of the Arenig strata on its borders, but what the features of that

land were I cannot say, except that it may have extended to Ireland, where there is a similar

unconformity, the Lingula flags and Tremadoc slates being also wanting in Wicklow. Probably

the whole region was low and unimposing.

The next question that arises is, what was the

[Geography. 79]

nature of the physical geography during the time of the volcanic eruptions already mentioned?

To me it seems to have been somewhat of this sort.

On the margin of the ancient land, or at some distance therefrom, volcanic eruptions took place

in the sea-bottom somewhat of the nature of that which in 1831 took place in the Mediterranean

between the islands of Pantellaria and the south-west coast of Sicily. This eruption was

preceded by an earthquake on June 28, and on July 10 John Corrao from his ship saw a column

of water 60 feet high and 800 yards in circumference spout into the air, succeeded by dense

steam, which rose to a height of 1,800 feet. On the 18th the same mariner found an island

twelve feet high, from the crater of which immense columns of steam and volcanic ashes were

being ejected, 'the sea around being covered with floating cinders and dead fish.'1 The eruption

continued into August, when, by the ejection of what is often called volcanic ashes, viz., pumice,

scoriæ, and lapilli, on the 4th of that month the island was said to have been more than 200 feet

in height and 3 miles in circumference. From that time it gradually decreased in size, owing to

the action of the waves, and towards the close of the year the island had been destroyed and

disappeared, leaving only a reef beneath the sea with a black rock in the centre, from 9 to 11

feet under water, and which probably marked the position of the funnel of the short-lived

volcano. Before the eruption took place it so happened that Captain (afterwards Admiral) W. H.

Smyth sounded on the spot in more than 100 fathoms, and this, added to 200 feet that the island

rose above the sea, gives 800 feet as the height of the cone from the

1 Lyell's 'Principles of

Geology,' vol. ii. p. 60, 12th editicn.

[8o Physical]

bottom of the sea to its summit. In a case such as this, it is easy to see that the ordinary marine

sediments of the area would get intermingled with volcanic ashes, and possibly with submarine

streams of lava.

Explosions of steam accompanied by floating cinders are mentioned by Darwin as occurring at

intervals in the South Atlantic; and anyone who will tax his memory a little will recollect that a

large proportion of the volcanoes of the world are islands, or in islands, in the Atlantic, the

Indian Ocean, the Indian Archipelago, and the Pacific Ocean, south and north. It has been often

remarked that almost all volcanoes are in the neighbourhood of the sea.

I think, then, at the time of the deposition of the Llandeilo and Bala beds of our area, our

terrestrial scenery consisted of groups of volcanic islands scattered over the area of what is

now North Wales and South Wales, and extending westward into the region of the Irish strata of

the same age, and northward as far as the sea that then rolled where Cumberland now stands; for

there also volcanic rocks occur in great force, all of the same general character as those found

in Wales. There is however, this difference between the two areas, that, whereas in Wales

ordinary sediments are plentifully interstratified with lavas and ashes, and sometimes even

lithologically intermingled with volcanic ashes, in the Cumbrian area it is only for a few feet at

the very base of the volcanic series that interstratifications take place, the whole of the rest of

these Silurian volcanic rocks of Westmoreland and Cumberland being quite destitute of any

intermixture of marine sediments. Exclusive of intrusive rocks, the whole consists of purely

terrestrial lavas, volcanic conglomerates and ashes, the latter often well stratified, for where

showers of ashes fall

[Geography. 81]

there layers of stratification will be formed, whether they fall in the sea or on land. It has been

suggested by Mr. Ward that some of this fine volcanic dust fell into lakes that filled old craters

or areas of subsidence during periods of partial repose, and this seems highly probable, for the

finely divided matter is so beautifully stratified, that these beds were, and still are by some,

mistaken for marine strata.

When we consider the vast amount of these products of ancient volcanoes, there can be no doubt

that, rising from the sea, some of them must have rivalled Etna in height, and others of the

great active volcanoes of the present day, and, as most volcanoes have a conical form, we can

easily fancy the magnificent cones of those of Lower Silurian age. But that is all we know

respecting them, and whether or not they were clothed, like Etna, with terrestrial vegetation,

no man can tell. It is hard to believe that they were utterly barren, but as yet no trace of a flora

has been found in Lower Silurian strata.

There is another point bearing on the physical geography of the time that has sometimes crossed

my mind in connection with these island volcanoes, which is, that we may, with some show of

probability, surmise, that then, as now, the prevalent winds of this region blew from the west

and southwest, for the following reason. In Merionethshire and Caernarvonshire the various

volcanic products gradually thin out and disappear to the west, between the ground south of the

estuary of the Mawddach, and the neighbourhood of Tremadoc on the north. As we pass round the

large crescent-shaped masses of lavas and ashes it becomes evident as a rule that the ashy

series of beds show a tendency to thicken more and more in an easterly direction for a space, and

finally to decrease in

[82 Physical Geography.]

thickness in the same direction, till, in the Bala country and further north, they are

represented only by a few insignificant beds of ashy strata, a character of which the Bala

limestone itself sometimes feebly partakes. The idea is, that the prevalent westerly winds had a

tendency during eruptions to blow the volcanic dust and lapilli eastward, and that these

materials fell thickest near the vents and at middle distances, and gradually decreased in

quantity the further east they were carried.

To those unaccustomed to technical geological arguments a word of warning remains. Let no

reader suppose that in Wales he will now find clear traces of these old volcanic cones and

craters in their pristine form, such, for example, as the extinct craters of Auvergne and the

Eifel. Semi-circular hollows surrounded by igneous rocks like those of Cwm Idwal and Cwm

Llafar he will find plentiful enough, and these, in old guide-books and other popular literary

productions, have sometimes been described as craters. So far from that being the case, such

cirques or corries are ancient valleys of erosion, the rocks of which have been exposed to the

weather perhaps ever since Upper Silurian times, and have been subsequently modified by

glaciers, during the last Glacial Epoch, in days, comparatively speaking, not far removed from

our own. The truth about these ancient volcanoes is, that long after they became extinct the

whole Lower Silurian area was disturbed and thrown into anticlinal and synclinal curves, which

suffered denudations before the beginning of the deposition of the Tipper Silurian rocks, and the

positions in which the lavas and ashes now stand will approximately be best understood, if we

suppose Etna by simlar disturbances to he half turned on its side,

[Lower Silurian Rocks, Scotland. 83]

and afterwards that the exposed portion should be irregularly cut away and destroyed by

processes of long-continued waste and decay, partly sub-aerial and partly marine.

The remaining areas in Great Britain occupied by Lower Silurian rocks lie in Scotland. The

southern district extends from St. Abbs Head on the east to Portpatrick on the west coast,

forming the uplands of the Lammermuir, Moorfoot, and Carrick Hills, fig. 55, p. 287. They

chiefly consist of thick banded strata of grits and slaty beds, much contorted, and in the western

part of the area, where bosses of granite and other igneous rocks occur, they are often

metamorphosed. The fossils which they contain prove them to belong to the Llandeilo, and Bala

or Caradoc series.

In Wigtonshire great blocks of gneiss, granite, &c. are imbedded in the dark slaty strata near

Corswall, and similar large blocks occur in Carrick in Ayrshire. Where they came from I

cannot say, for all the nearest granite bosses in Kirkcudbrightshire and Arran are of later date

than the strata amid which these erratic blocks are found. I therefore incline to the opinion that

they must have been derived from some Laurentian region, of which parts of the mainland and of

the Outer Hebrides then formed portions, and when I first saw them I could, and still can

conceive of no agent capable of transporting such large blocks, and dropping them into the

graptolite-bearing mud, save that of icebergs. One of the blocks measured by me near Corswall,

in 1865, is 9 feet in length, and they are of all sizes, from an inch or two up to several feet in

diameter. Many persons have considered, and will still consider, this hypothesis of their origin

to be overbold, but I do not shrink from repeating it, and I may mention that the same view

[84 Lower Silurian Rocks.]

with regard to these ancient boulder beds is held by Professor Geikie and Mr. James Geikie, who

mapped the country.1

The Lower Silurian rocks of the south, pass underneath the Old Red Sandstone and Carboniferous

rocks of the midland parts of Scotland, and rise again on the north in the Grampian Mountains. A

great fault,

1

I shall by-and-by have to notice the recurrence of glacial episodes at various epochs in

geological history, a subject with which ever since 1855 I have had a good deal to do. (On

Permian Breccias, &c. 'Journal of the Geol. Soc.' vol. ii. p. 185). It is difficult to make out the

ground on which all the old, and many of the middle aged geologists, have cast aside the various

evidences that have been adduced in support of the recurrence of glacial epochs or episodes,

especially as I remember no argument that has been brought forward, excepting that in old

times, the radiation of internal heat through the crust of a cooling globe, produced warm and

uniform climates all over the surface, and that the further you go back in time the hotter they

were. The Lias was accumulated in warm seas, and, if so those of the Carboniferous times were

warmer, and those of Silurian times warmer still, and I have heard a distinguished geologist

declare in a public lecture, that the tropical vegetation of the Coal-measures, was due to the

heat that radiated outwards from the earth's crust, aided by that produced by the flaring

volcanoes of that epoch! Undoubtedly there must have been a geologically prehistoric time, when

internal heat may have acted on the surface, and perhaps the sun may have been hotter than

now, and that also had its effect. I, however, can see no signs of these internal and external

interferences since the times in which the authentic records of geological history have been

preserved, and these extend backward earlier than the Lower Silurian epoch. I recollect the

time when what passed for strong arguments were urged to prove that the former great

extension of the Alpine glaciers advocated by Agassiz, and the existence of glaciers in the

Highlands, Cumberland, and Wales, proved by him and Buckland, were mere myths. Now,

however, there is such a persistent run upon the subject, that more memoirs have been, and

still are being, written about it, than persaps on any other geological question. Coincident with

this a beginning of the acceptance of the theory of the recurrence of glacial episodes, is slowly

making its way both in England and the Continent.

[Scotland. 85]

proved by Professor Geikie, runs at the base of that so-called chain right across Scotland, from

the neighbourhood of Stonehaven on the east coast, to Loch Lomond on the west. Its effect is to

throw down the Old Red Sandstone on the south-east, partly against the Silurian rocks, and

partly against volcanic tufas and other strata belonging to the Old Red Sandstone itself. From

that region, nearly the whole of the Highlands, from the Grampians to the north coast of Scotland

consists of Lower Silurian rocks often intensely contorted, and formed of quartz-rocks and

flagstones, gneissic and micaceous schists, clay slate, and chlorite slate. Associated with these,

there are certain limestones, sometimes crystalline, but where less altered, sometimes

fossiliferous, fig. 55, p. 287. One of these, near the base of the Silurian series, runs in a long

band from Loch Erriboll, on the north coast, southward to Loch Broom, where for a space of

about fifteen miles it is lost, to reappear between the east side of Sleugach and Loch Carron. The

same limestone is well seen in the Island of Lismore in Loch Linnhe, and here and there on the

sides of Strathmore or the Great Glen (a line of fault), through which the Caledonian Canal was

constructed. Elsewhere in the Highlands, further east, streaks of limestone occur. Immense

masses of granite here and there rise in the midst of the strata, one of the smaller of which

forms great part of Ben Nevis, the highest mountain in Britain, 4,406 feet in height, and

another the splendid peaks of the Island of Arran. No interbedded igneous rocks have yet been

found among the Silurian rocks of Scotland.

The strata of the Highlands, not of Lower Silurian age, are the Laurentian gneiss and Cambrian

conglomerates and sandstones already mentioned, intersected by

[86 Lower Silurian Rocks, Scotland.]

so many noble Fjords between Sleat and Cape Wrath, while on the east there are large tracts of

Old Red Sandstone, more or less extending from Thurso in Caithness to the Great Glen, Moray

Firth, the river Spey, and yet further east. Fig. 55, p. 287.

In times within the memory of the writer, all these metamorphic rocks of the Highlands were

classed in Wernerian style as Primitive strata, thrown down in hot seas before the creation of

life in the world. The progress of research showed that gneiss and other rocks now called

metamorphic, are of many geological ages; and the fortunate discovery of fossils in these strata,

at Durness, by Mr. C. Peach, in 1854, showed them to be of Arenig ages a discovery the

importance of which was at once seen by Sir Roderick Murchison, who by this means,

revolutionised the geology of the greater part of the northern half of Scotland. Feeling anxious to

have a second opinion respecting the justness of his new views, he asked me to accompany him

on a long tour through the northern Highlands in 1859, when I mapped part of the country at

Durness and Loch Eriboll, and the whole matter seemed to me so plain, that the wonder is, that

any man with eyes ever dreamed of disputing it. In these days no one now thinks of denying the

Lower Silurian age of the chief part of the gneissic rocks of Scotland, the features of which have

been mapped by Professor Geikie, first in concert with Sir Roderick Murchison, and afterwards

personally in more detail.1

With regard to the physical geography of the time, little is certain but this, that almost the

whole of the area now called Scotland was under the sea, during the time

1

See 'Geological Map of Scotland,' last edition, by Archibald Geikie, LL.D., F.R.S., 1876.

[Physical Geography. 87]

that these Lower

Silurian strata were being deposited. The only sign of pre-existing land,

is found on the west coast between Cape Wrath and Loch Torridon, where the

Llandeilo beds lie alike unconformably on the Cambrian and Laurentian strata.

This proves, that when the lowest Llandeilo beds began to be deposited, the

underlying rocks formed the eastern margin of a territory, of which probably

our Outer Hebrides was only a part, but how far it may have stretched westward

it is impossible to say. However that may have been, it seems certain that

long before the uppermost strata of the Lower Silurian rocks of Scotland

were deposited, these fragments of an older land, which are still preserved

on the west, had been long submerged and buried under the accumulating piles

of the Silurian strata. That even then an extensive land lay not far off

is certain, for the extent and great thickness of the Lower Silurian rocks

affords a measure of the amount of waste of a pre-existing territory, the

partial and gradual destruction of which, by all the agencies of denudation,

provided mechanical sediments wherewith to form thousands of feet of Silurian

strata of mud and sand, first consolidated, and long after metamorphosed

into quartzite, gneiss, and mica-schist. This land may have occupied an area

now covered by the Atlantic ocean.