[302]

CHAPTER XIX.

RECAPITULATION

OF THE GENERAL ARRANGEMENT OF THE STRATIFIED FORMATIONS OF

ENGLAND.

THE geology of England and Wales is much more comprehensive than that

of Scotland, in so far

that it contains many more formations, and its features therefore are

more various. England is

the very Paradise of geologists, for it may be said to be in itself an

epitome of the geology of

almost the whole of Europe, and much of Asia and America. Very few

European geological

formations are altogether absent in England. On the Continent, however,

some have a larger

importance than in England, being more truly oceanic deposits in some

cases, and more

thoroughly developed lacustrine or terrestrial deposits in others. In

some countries larger than

England the whole surface is occupied by one or two formations, but in

England nearly all the

formations shown in the column (p. 30) are more or less developed.

Those of Silurian age lie

chiefly in England, in Cumberland and Westmoreland, and in the west, in

Wales (fig. 57, p.

304). Above them lie the Old Red Sandstone and Devonian rocks,

occupying large areas in

Herefordshire, Worcestershire, South Wales, and in Devonshire and

Cornwall. Above the Old

Red Sandstone come the Carboniferous strata, which form large tracts of

Devonshire, Somerset, and part of Gloucestershire,

[English Formalions. 303]

and in South Wales skirt the Bristol Channel, and stretch into the

interior in Pembrokeshire,

Glamorganshire, and Monmouthshire; while in the north they border North

Wales, and form a

broad backbone of country that reaches from the borders of Scotland

down to North

Staffordshire and Derbyshire. Other patches, here and there, rise from

below the Secondary

strata into the heart of England. (See Map.)

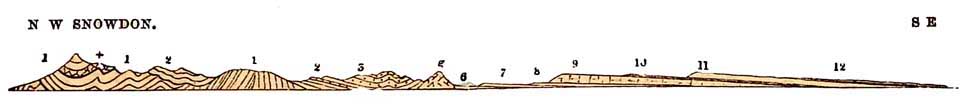

The general physical structure of England, from the coast of Wales to

the Thames, will be easily

understood by a reference to fig. 57, p. 304, and to the following

descriptions; and this

structure is eminently typical, explaining, as it does, the physical

geology of the greater part of

England south of the Staffordshire and Derbyshire hills.

The Lower

Silurian rocks of

Wales (No. 1) consist chiefly of slaty and solid gritty strata,

accompanied

by, and interbedded with, numerous feispathic lavas and beds of

volcanic

ashes, marked + ; and mingled with these there are numerous bosses and

dykes

of felstone, quartz-porphyry, greenstone (diorite), and the like. These

last,

by their superior hardness, give a mountainous character to the whole

of

North Wales, from Merionethshire to the Menai Straits. In part of north

Pembrokeshire

also, in a less degree, igneous rocks are largely intermingled with the

Lower

Silurian strata, and these, by help of denudation, now form a very

hilly

country.

Without again entering into details, it is here sufficient to state

that the Cambrian arid Lower

Silurian epoch was ended in the British area by disturbance and

contortion of the strata, and

their upheaval into land. This disturbance necessarily gave rise to

long-continued denudations

of this early English land, both by ordinary

[303]

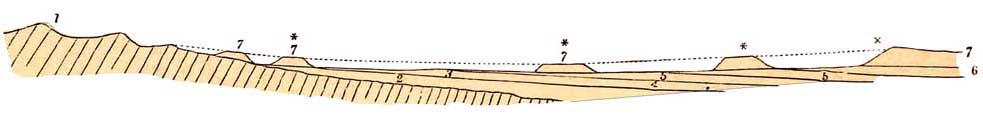

FIG.

57

Diagrammatic Section from the Menai Straits across Wales, the Malvern

Hills, and the

Escarpments of the Oolitic Rocks and the Chalk See Map, line 6.

Nos. 1 to

3, 5, and g represent the disturbed Cambrian, Lower and Upper Silurian,

and Old

Red Sandstone mountainous country of North Wales, the adjacent

countries on the east, and the

Malvern Hills g.

6 to 8 the plains and slightly undulating grounds of the New Red

Sandstone, Red Marl, and Lias.

9 and 10 the great Oolitic escarpment of the Cotswold Hills, forming

the first tableland.

11 the great escarpment of the Chalk, forming a second tableland, above

which lie the Eocene

strata, 12.

The Upper Oolites, close below the Chalk escarpment 11, are in places

of less height relatively to

the sea than the edge of the Oolitic escarpment at 9.

[English Formations. 305]

atmospheric agencies, and also by the action of the waves of the sea of

a younger Silurian period,

the evidence of which is seen in the conglomerates of the Upper

Llandovery beds, which,

mingled with marine shells, lie unconformably on the denuded edges of

the Cambrian and Lower

Silurian strata of the Longmynd in Shropshire, like a consolidated sea

beach. Slow submergence

then took place beneath the Upper Silurian sea, in which the Upper

Silurian rocks were

gradually accumulated unconforinably till, perhaps, they entirely

buried the Lower Silurian

strata (2, fig. 57), for in places they attained a thickness of from

three to six thousand feet.

As shown in Chapter VIII. the uppermost Upper Silurian beds of Wales

pass insensibly into a

newer series, known as the Old Red Sandstone (3, fig. 57), formed, if

we include the entire

formation, of beds of red marl, sandstone, and conglomerate, which in

all the British areas by

the absence of marine shells, and the occasional presence of

crocodilians, land reptiles, and of

fish (whose nearest allies live in the rivers and lakes of America and

Africa, or in the brackish

pools of Australia), seem to have been deposited in lakes. In Wales,

these strata again pass

upwards into the Carboniferous Limestone, which is overlaid in Wales,

Derbyshire, and,

Lancashire, by the Millstone Grit and the Coalmeasures.1

In Yorkshire, Durham, Northumberland, and Scotland, the Carboniferous

Limestone has no

pretension to be ranked as a special formation, for it is broken up

into a number of bands

interstratified with masses of

1 This is not shown in

fig. 57, but the Carboniferous Limestone No. 4 is shown in fig. 67, p.

330, lying, as it does in North Wales, unconformably on Silurian rocks.

[306 English Formations.]

shales and sandstones bearing coals. In fact, viewed as a whole, the

Carboniferous series

consists only of one great formation, possessing different lithological

characters in different

areas, these having been ruled by circumstances dependent on whether

the strata were formed

in deep, clear, open seas, or near land; or actually, as in the case of

the vegetable matter that

forms the coals, on the land itself.

The English Carboniferous rocks differ from the Scottish beds in this,

that in general they have

not been mixed with igneous matter, except in Northumberland and

Derbyshire, where, in the

last-named county, the Carboniferous Limestone is interbedded with

ashes and lava, locally in

Derbyshire called 'toadstones.' In South Staffordshire, Colebrook Dale,

the Clee Hills, and

Warwickshire, there is a little basalt and greenstone, which may

possibly be of Permian age,

intruded into, and perhaps also partly overflowing, the Carboniferous

rocks in Permian times;

but in Glamorganshire, Monmouthshire, North Staffordshire, Lancashire,

and Yorkshire, where

the Coal-measures are thickest, no igneous rock of any kind occurs.

There and elsewhere in

England the Coal-measures as usual consist of alternations of

sandstone, shale, coal, and

ironstone.

Next in the series come the Permian rocks (2, 3, 4,

fig. 30, p. 141), which, however, rarely occupy so great a space in

England, as materially to

affect the larger features of the scenery of the country. They form a

narrow and marked strip on

the east of the Coalmeasures from Northumberland to Nottinghamshire,

where they chiefly consist of a long, low, flat-topped terrace of

Magnesian limestone (see

Map), interstratified

[English Formations. 307]

with two or three thin beds of red marl sometimes containing gypsum.

The scarped edge of this

limestone, which is sparsely fossiliferous, faces west, and overlooks

the lower undulations of

the Coal-measure area.

There are

other patches of

Permian sandstones, mans, breccias, and conglomerates, in the South of

Scotland,

the Vale of Eden, and the West of Cumberland, and they are also here

and

there present on the borders of the Lancashire, North Wales,

Shropshire,

and all the Midland coal-fields, and on the Silurian rocks o the

Abberley

and Malvern Hills. Throughout all the districts enumerated above, these

Permian

strata chiefly consist of red sandstones, conglomerates, and mans, and

part

of them, in the districts of the Malvern and Abberley Hills, near

Enville,

and at Bromsgrove, consist of consolidated true Permian glacial

boulder-clays.

The Permian beds form the uppermost members of the so-called

Palæzoic or old-life period—a

term somewhat unphilosophical, in so far that it partly conveys a false

impression of a life

essentially distinct from that of later times. But it is at present

convenient, for all geologists

know when the word palozoic is used what formations are meant,

embracing all the strata from

those of Permian date down to the lower Laurentian. During the time

they were forming, this

and other parts of the world suffered many oscillations of level,

accompanied by denudations, as

shown in previous chapters.

Before the end of this Palaeozoic epoch, the Permian beds were

deposited in great inland salt

lakes, analogous to the Caspian Sea and other salt lakes in Central

Asia, at the present day. That

area gives the best modern idea of the state of much of the world

during Permian times.

[308 English Formations.]

In the same continental area, and partly on the Permian rocks, partly

on older subjacent strata,

the New Red Sandstone and Marl of our region were then deposited in

lakes perhaps occasionally

fresh, but as regards the marl certainly salt. These formations fill

the Vale of Clwyd in North

Wales, and in the centre of England range from the mouth of the Mersey

round the borders of

Wales to the estuary of the Severn, eastwards into Warwickshire, and

thence northwards into

Yorkshire, along the eastern border of the Magnesian limestone (see

Map). They are absent in

Scotland. In the centre of England the unequal hardness of its

subdivisions sometimes gives rise

to minor escarpments (Nos. 4 and 6, fig. 32, p. 154), most of them

looking west over plains

and undulating ground formed of soft red sandstone. Such escarpments

are especially

remarkable in the case of the Keuper sandstone, which lies at the base

of the New Red Marl.

These strata

frequently form a good building stone, often white, and because of

their hardness having better

resisted denudation than the red sandstones below, they stand out as

bold cliffy scarps facing

west, with long gentle slopes to the east. Such are Hilsby lull, that

looks out upon the Mersey,

near Frodsham; the beautiful terraced scarps of Delamere Forest, the

grand castle-crowned cliff

of Beeston by the North Western Railway, near Tarporley, and the

beautiful heights, often well

wooded, that stretch from thence to the south, and form the Peckforton

Hills. There, among spots

that haunt

the memory, in the ancient park of Carden, scarped by nature and cut

into terraced walks and

caverns,

among the red and white cliffs grow great rhododendrons, which sow

themselves in every mossy

cleft of the rocks; luxuriant brackens, male ferns, lady ferns,

[English Formations. 309]

Lastræas, and others of smaller growth, while all forest trees

attain a goodly growth, and low

down in the flat, deer are grazing up to the gates of the old

broadfronted timbered Hall. It is

indeed a splendid sight to stand on the edges of these scarped hills

and look across the great

rolling plains of New Red Sandstone below, bounded by Moel Famau and

all the mountains of

North Wales that surround the beautiful Vale of Clwyd; or twenty miles

further south, from the

abrupt cliff of Grinshill, to see the tall spires of Shrewsbury backed

by the renowned Caer

Caradoc, the Wrekin, the high line of the flat-topped Lougmynd, and the

craggy Stiper Stones.

The New Red Marl passes insensibly into the Rhætic beds, which

again pass insensibly into the

Lower Lias. In England there is therefore a gradation between the New

Red Marl and the Lower

Lias.

The Lias series, Nos. 3, 4, 5, fig. 5, consists of three belts of

strata, running from Lyme Regis

on the south-west, through the whole of England, to Yorkshire on the

north-east: viz. the Lower

Lias clay and Limestone, the Middle Lias or Marlstone strata, and the

Upper Lias clay. The

unequal hardness of the clays and limestones of the Liassic strata

causes some of its members to

stand out in distinct minor escarpments, often facing west and

north-west. The Marlstone No. 4,

forms the most prominent of these, and overlooks the broad meadow-land

of Lower Lias clay

that form much of the centre of England.

Conformable to and resting upon the Lias are the

various members of the Oolitic series (6 to 11, fig. 5).1

That portion termed the Inferior Oolite occupies the base, being

succeeded by the Great or Bath

Oolite,

1 See also the 'Column

of Formations,' p. 30.

[310 English Formations.]

Cornbrash, Oxford Clay, Coral Rag, Kimeridge Clay, and Portland beds.

These, and the

underlying formations, down to the base of the New Red Sandstone,

constitute what geologists

term the Older Mesozoic or Secondary formations, and all of them, from

their approximate

conformability one to the other, occupy a set of belts of variable

breadth, extending from Devon

and Dorsetshire northwards, through Somersetshire, Gloucestershire, and

Leicestershire, to

the north of Yorkshire, where they disappear beneath the German Ocean.

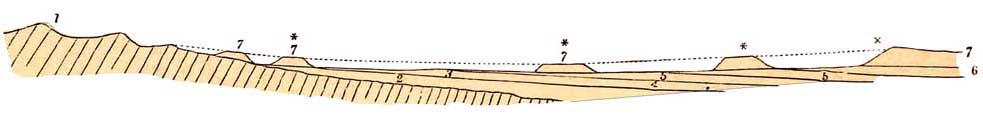

FIG.

58.

1. Portland

Oolite.

2. Purbeck Limestones

and Marls.

3. Wealden Sands and

Clays.

4.

Cretaceous

strata.

When the Portland beds had been deposited (see figs. 39 and 58), the

entire Oolitic series, in

what is now the south and centre of England, and much more besides in

other regions, was raised

above the sea-level and became land. Because of this elevation, there

is evidence in the Isles of

Purbeck, Portland, and the Isle of Wight, and in the district known as

the Weald, of a state of

affairs which must have been common in all times of the world's

history. We have there a series

of beds, consisting of clays, loose sands, sandstones, and shelly

limestone, indicating, by their

fossils, that they were accumulated as a delta and in lagoons in an

estuary, where fresh water

and occasionally brackish water and marine conditions prevailed at the

mouth of a great

continental river. The position of these beds, with respect to the

Cretaceous strata, will be seen

in

[English Formations. 311]

fig. 72, p. 339, marked w, h, proving that they are

intermediate in date to the Oolites and

Cretaceous rocks, for in the Isle of Purbeck, near Swanage, they are

seen lying between the two

(fig. 75, p. 348).

This episode at last came to an end, by the complete submergence of the

Wealden area, and of the

greater part of England besides; and upon these fresh-water strata, and

the Oolitic and other

formations that partly formed their margins, a set of marine sands and

clays were deposited in

the south of England, consisting of the Atherfield Clay and the Lower

Greensand s, d (fig. 72, p.

339) is now often classed with the Upper Neocomian beds of the

Continent, but in England they

have till lately generally been known as the Lower Cretaceous strata.

The distinction is not

important to my present purpose. Then comes the clay of the Gault,

above which lies the Upper

Greensand. Resting upon the Upper Greensand comes the Chalk (No. ii,

fig. 57, and c. fig. 72),

the upper portion of which contains numerous bands of interstratified

flints, which originally

were partly marine sponges, since silicified. The Chalk, where

thickest, is from one thousand to

twelve hundred feet in thickness. The Liassic and Oolitic formations

were sediments spread in

warm seas sirrounding an archipelago of which Dartmoor, Wales,

Cumberland, and the

Highlands of Scotland formed some of the islands. But the Chalk was a

deep sea deposit, formed to

a great extent of microscopic foraminifer, and while it was forming in

the wide ocean, it seems

probable that the old islands of the Oolitic seas subsided so

completely, that it is doubtful

whether or not even Wales and the other older mountains of Britain were

almost entirely

submerged.

During the period that the Oolitic formations formed

[312 English Formations.]

part of the land through which the river flowed that deposited the

Wealden and Purbeck beds,

they were undergoing constant waste, so that in the course of time,

having been previously

tilted upwards to the west with an eastern dip (fig. 59), they were

worn into what I. have

elsewhere termed a plain of marine denudation (see p. 497). The

submergence of the Wealden

area was followed by the progressive sinking of the Oolitic and older

strata further west, so

that, as the successive members of the Cretaceous formations were

deposited, it happened that

by slow sinking of the land, the Upper Cretaceous strata gradually

overlapped the edges of the

outcropping Oolitic and Liassic formations, till at length they were

intruded on the New Red

series, and even on the Palæozoic strata of Devonshire itse1f, as

shown in fig. 59.

The upheaval of the Chalk into land brought this epoch to an end, and

those conditions that

contributed to its formation ceased in our area. As the uppermost

member of the Upper

Secondary rocks, it closes the record of Mesozoic times in England.

This brings us to the last divisions of the British strata which I

shall now name. These were

deposited on the Chalk, and are termed Eocene formations (No. 12, fig.

57, p. 304). At the base

they consist of marine and estuary deposits, known as the Thanet Sand,

and Woolwich and

Reading beds, and which are of comparatively small thickness, say from

50 to 150 feet. These

lie below the London Clay and form the outer border of the London

basin. The Woolwich and

Reading beds are found in the Isle of Wight, and in part constitute the

Hampshire and London

basins. In these we have in places the same kind of alternations of

fresh

[313 English Formations.]

FIG.

59

Overlap of the

Oolitic and other Strata by Cretaceous Formations.

Overlap of the

Oolitic and other Strata by Cretaceous Formations.

1.

Represents the Paleozoic strata. 2. The New Red beds. 3. The Lias. 4,

5, 6. Various members

of the Oolites, and 7. The upper Cretaceous strata. The dotted line

represents the original

continuation of the Chalk westward, the slope marked x the present

escarpment of the Chalk, and

the hills marked with asterisks (*) outlying patches of the same, the

relics left by old

denudations, and which help to prove the original far westward

extension of the Upper Cretaceous

strata.

[314 English Formations.]

water and marine shells that I mentioned as occurring in the Wealden

and Purbeck strata; but

with this difference, that though the shells belong mostly to the same

genera, they are of

different species—the old freshwater life is replaced by new.

Upon the London Clay, which is a marine formation, varying from 200 to

500 feet thick, the

Bracklesham and Bagshot beds were deposited. These consist of marine

unconsolidated sands and

clays, occurring as outliers—isolated patches left by denudation around

Bagshot, and elsewhere

on the London Clay, and overlying the same formation in the Isle of

Wight, where they are well

seen in Alum Bay. In both these places they are only sparingly

fossiliferous, but at Bracklesham

and Barton, on the Hampshire coast, they contain a rich marine

molluscan fauna of a tropical or

subtropical character. Upon these were formed various newer fresh-water

strata, occasionally

interbedded with thin marine bands, the whole evidently accumulated at

the mouth of a river.

For the names of these minor formations, I refer the reader to the

column, p. 30.

I have in this chapter given a brief recapitulation of the geological

and stratigraphical positions

of the series of the larger and more solid geological formations that

are concerned in producing

the physical structure of England (see Map), and I will in the

following chapters endeavour to

show by the help of fig. 57, and other diagrams, the part that these

formations play in

producing the scenery of the country.