[315]

CHAPTER XX.

THE MOUNTAINS OF DEVON, WALES, AND THE WEST OF ENGLAND—THE VALLEY OF THE SEVERN,

AND THE OOLITIC AND CHALK ESCARPMENTS—THE HILLY CARBONIFEROUS GROUND OF THE

NORTH OF ENGLAND, AND ITS BORDERING PLAINS AND VALLEYS—THE PHYSICAL RELATION OF

THESE TO THE MOUNTAINS OF WALES AND CUMBERLAND.

IN the far west, in Devon and in Wales, also in the north-west, in Cumberland, and in the

Pennine chain which joins the Scottish hills, and stretches from Northumberland to the

Carboniferous Limestone hills of Derbyshire north of Ashbourne, we have what forms the

mountainous and more hilly districts of England and Wales.

In Wales, especially in the north, the country is essentially of a mountainous character; and the

middle of England, such as parts of Staffordshire, Worcestershire, and Cheshire, may be

described as flat and undulating ground, sometimes rather hilly. But, as a whole, these midland

hills are insignificant, considered on a large scale, for when viewed from any of the more.

mountainous regions in the neighbourhood, the whole country below appears almost like a vast

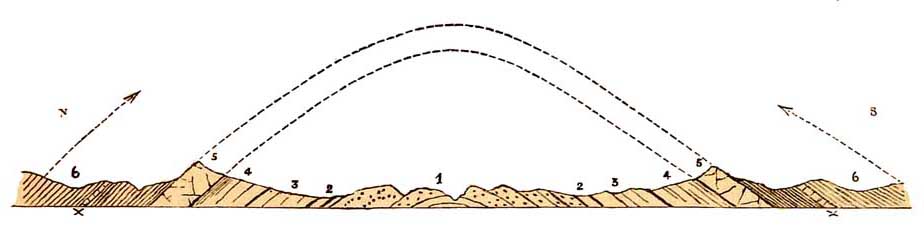

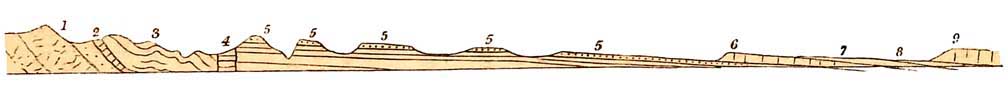

plain. To illustrate this. [sic.] Let us imagine any one on the top of the gneissic range of the Malvern

Hills (g, fig. 57, p 304), which have, on a small scale, something of a

[316 View from Malvern Hills.]

mountainous character, and

let him look to the west: then, as far as the eye can reach, he will see

hill after hill stretching into Wales (1 to 3, fig. 57); and if he cast his

eye to the northeast, he will there see what seem in the distance to be interminable

low undulations, looking almost like perfect plains; while to the east and

south-east there lies a broad low flat (6 to 8), through which the Severn

flows, bounded by a flattopped escarpment (9) facing west, and rising boldly

above the plain. This escarpment is formed of the Oolitic formations, which

constitute so large a part of Gloucestershire. These, as the Cotswold Hills,

form a tableland, overlooking on the west a broad plain of Lias Clay and

of New Red Marl, across which, on a clear day, from the scarped edge of North

Gloucestershire, far to the west, we may descry the whole of the Malvern range,

the well-known clump of firs on the top of May Hill near the Forest of Dean,

and away to the north, the distant smoke of Colebrook Dale.

This remarkable Oolitic escarpment stretches, in a more or less perfect form, from the

extreme south-west of England northward into Yorkshire (see Map). But it is clear that the

Oolitic strata could not have been originally deposited in the scarped form they now possess, but

once spread continuously over the plain far to the west, and only ended where the Oolitic seas

washed the high land formed by the more ancient disturbed Palæozoic strata of Dartmoor,

Wales, and the North of England. Occasional outliers of Lias and Oolite attest this fact, as, for

example, in the large outlier of Lower Lias and Maristone between Adderley and the

neighbourhood of Whitchiirch in Cheshire and Shropshire. This outlier occupies an area of

about 50 square miles, and is at least 50 miles distant from the main mass of

[Oolilic Escarpment and Tableland. 317]

the nearest Lias, near Droitwich in Worcestershire. Indeed, I firmly believe that the Lias and

Oolites entirely surrounded the old land of Wales, passing westwards through what is now the

Bristol Channel on the south, and the broad tract of New Red formations, now partly occupied by

the estuaries of the Dee and Mersey, that lie between Wales and the Carboniferous rocks of the

Lancashire hills.

The strata that now form the wide Oolitic tableland, have a slight dip to the south-east and east,

and great atmospheric denudations having in old times taken place, and which are still going on,

a large part of the strata, miles upon miles in width, has been swept away, and thus it happens

that a bold escarpment, once-for a time in Yorkshire and the Vale of Severn—an old line of

coast cliff, overlooks the central plains and undulations of England, from which a vast extent and

thickness of Lias and Oolite have been removed. That the sea was not, however, the chief agent in

the production of this and similar escarpments will be shown further on.

An inexperienced person standing on the plain of the great valley of the Severn, near

Cheltenham or Wottonunder-edge, would scarcely expect that when he ascended the Cotswold

Hills, from 800 to 1,200 feet high, he would find himself on a second plain (9, fig. 57, p.

304); that plain being a high tableland, in which here and there deep valleys have been scooped,

chiefly opening out westward into the plain at the foot of the escarpment. These valleys have

been cut out entirely by frost, rain, and the power of brooks and minor rivers.1

If we go still farther to the east, and pass in

1

Such valleys are necessarily omitted on so small a diagram, and the minor terraces on the plain,

especially such as 7, are exagerated.

[318 Chalk Escarpment and Eocene Outliers.]

succession all the outcrops of the different Oolitic formations (some of the limestones of which,

overlying beds of clay, form minor scarps), we come to a second grand escarpment (11, fig.

57), formed of the Chalk, which in its day also spread far to the west, covering unconformably

the half-denuded Oolites, till it also abutted upon the ancient laud formed of the Palaeozoic

strata of Wales, and by-and-by, as that land sunk in the sea, buried it in places altogether.

After consolidation and emergence, this Chalk formation also suffered great waste, and the

result is this second bold escarpment also facing westerly, which stretches from Dorsetshire on

the south coast of England into Yorkshire north of Flamborough Head. Occasional outlying

patches of the Cretaceous formations attest its earlier western extension in the south-west of

England, and the same overlap may be inferred with justice respecting the relations of the

Oolitic, Triassic, and Upper Cretaceous strata throughout the length and breath of England. (See

fig. 59, p. 313.)

The Eocene strata, which lie above the Chalk, in their day also extended much farther to the

west, because here and there, near the extreme edge of the escarpment of Chalk, we find

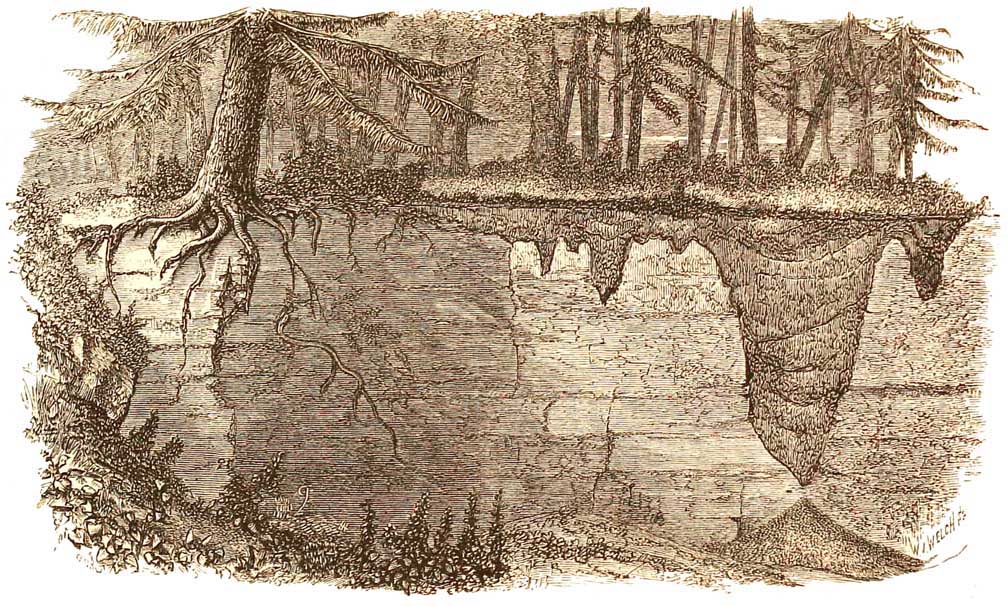

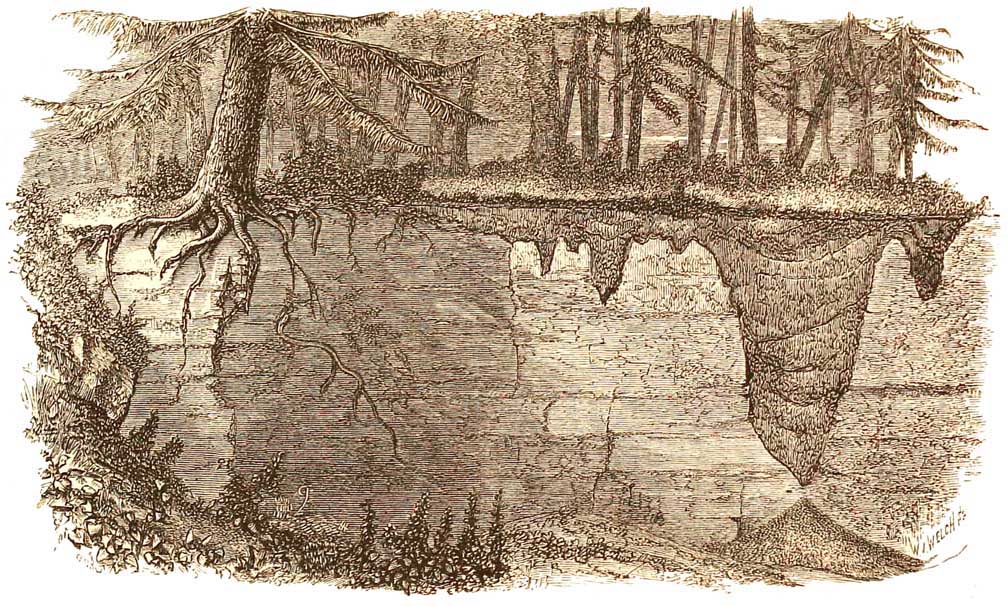

outlying Eocene fragments, and potholes more or less filled with the relics of Eocene strata. On

the opposite page there is a drawing of such potholes filled with relics of the Plastic Clay of the

Woolwich and Reading beds, which in and round Savernake Forest generally overlie the Chalk in

a mere thin covering of red and mottled clay and yellow sand, often mixed with a few rounded

flint pebbles. On the top of all there is frequently a layer of semi-angular high level gravel, and

all of these have been more or less let down into the potholes, by the dissolving of the

underlying chalk

[319]

FIG. 60

Potholes in the Chalk of Savernake Forest, near Marlborough.

[320 Eocene Outliers.]

by the carbonic acid in rain-water, and thus pockets of Eocene strata have been preserved. The

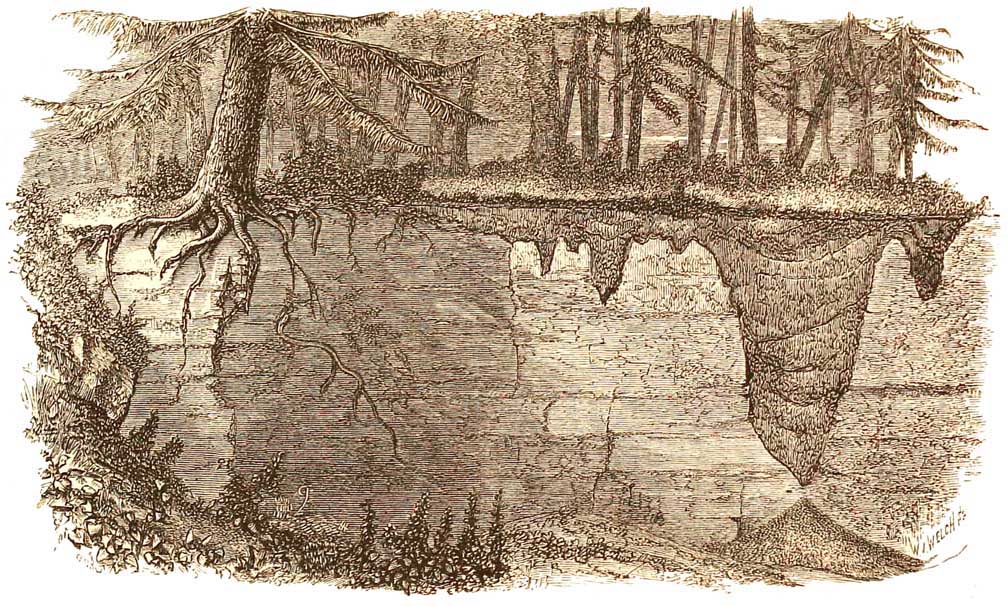

proof of this original extension westward is shown in the following diagram.

FIG. 61.

1. Chalk. 2. Part of the main mass of the Eocene beds. 2'. Outlying patch of the Eocene beds near

the edge of the escarpment.

It is impossible that these

outliers could have been originally deposited on this the edge of the Chalk,

and not also on other strata that lie west of the present escarpment, and

therefore it may be assumed that they originally extended further westward,

and ith the Chalk, have been denuded backwards till they occupy their present

area. But the Eocene beds being formed of soft stratachiefly clays and sands-though

they make undulating ground, form no bold scenery. They rest in patches on

the tableland, or in a large and somewhat depressed area in a manner shown

at 12, fig. 57.1 Such is the general manner in which the southern part of

England has attained its present form.

Nearly the whole of the west of England, that is to say, of Devon and Cornwall, and of Wales,

consists of Palaeozoic strata, viz.: Devonian and Old Red Sandstone, Cambrian, and Silurian with

all its igneous intersiratifications,

1 Were I going into extreme details on this part of the subject, there are many distinctive

features in the scenery of the Eocene formations dependent on synclinal curves in the strata, and

other accidents, and the same remark may be extended to the scenery of many formations more

important in a scenic point of view. The plan of this book purposely excludes such details, my

object being merely to explain the connection of the greater geological features of the country

with its physical geography.

[Merionethshire and Denudation. 321]

and of the Carboniferous series, all of which have been much disturbed and

extensively denuded.

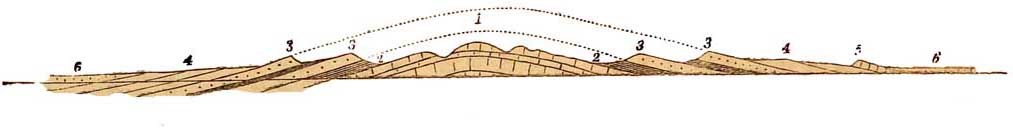

The Cambrian rocks of Merionethshire,

for example, marked 2 on the map, were once buried deep beneath more than

20,000 feet of Lower Silurian strata. Let anyone climb to the rugged centre

of this Cambrian area, and stand on the summit of the great grit-formed cliffs

of Rhinogfawr or of Y-Graig-ddrwg (the bad cliff). From thence turning to

the south and south-east, he will see the long ridgy peaks of the interstratified

feistones and ashes of Cader Idris and Aran Mowddwy, further northeast the

serrated edges of Moel Llyfnant and the Arenigs, and the circle is continued

on the northern side of the Cambrian strata by the noble heights of the Manods

and the Moelwyns near Ffestiniog and Portmadoc. On three sides the great

anticlinal boss of Cambrian grits is set in a curved frame of Silurian slates

and volcanic beds, and on the fourth it is bordered by the sea. All these

rocks, and much more besides, once overlaid the Cambrian beds, in the form

of a great anticlinal curve, and have since been removed by denudation; and

thus it happens that between the estuary of the Mawddach below Dolgelli,

and that of Traethbach at Portmadoc, we find this inner group of gritty hills,

more than half enclosed by that somewhat distant ring of higher mountains,

which are highest, as a rule, simply because of the hard quality of the great

inclined beds of porphyries, of which they are so largely composed. (Fig.

62.)

In this brief account of a fragment of North Wales of about 1,200 square miles, lies the essence

of the matter, for with differences of detail, the whole of the strata suffered an equal amount of

disturbance and denudation, and the history simply comes to this. Much

[322 Lower Silurian Rocks.]

FIG. 62

Section across the Cambrian and part of the Lower Silurian rocks of Merionethshire.

Section across the Cambrian and part of the Lower Silurian rocks of Merionethshire.

1. Cambrian grits. 2. Menevian. 3. Lingula flags. 4. Tremadoc and Arenig slates. 5. Igneous

series. 6. Llandeilo and Bala. x Bala limestone.

[Mountains and Tablelands. 323]

of the Silurian rocks in North Wales are of a slaty character, interbedded with masses of hard

igneous rocks, which attain in some instances a thickness of thousands of feet. It is, therefore,

easy to understand how it happens that with disturbed and contorted beds of such various kinds,

those great denudations, which commenced as early as the close of the Lower Silurian period,

and have been continued intermittently ever since, through periods of time so immense that the

mind refuses to grapple with them—it is, I repeat, easily seen how the outlines of the country

have assumed such varied and rugged outlines, as those which North Wales, and in a less degree

parts of North Pembrokeshire, Devon, and Cornwall, now present.

I have said that the Secondary and Lower Tertiary strata have not been anywhere disturbed

nearly to the same extent as the Palieozoic formations in England. Though occasionally traversed

by faults, yet with rare exceptions most of the strata have been elevated above the water

without much bending or contortion on a large scale. What chiefly took place was a slight

uptilting of the strata to the west, which, therefore, all through the centre of England, dip as a

whole slightly but steadily to the east and south-east. This is evident from the circumstance that

on the Cotswold Hills the lowest Oolitic formation (Inferior Oolite, No. 9, fig. 57) forms the

western edge of the tableland, while, in spite of a few minor escarpments that rise on the

surface of the upper plain, the uppermost Oolitic beds that dip below the Cretaceous strata, are

sometimes at a lower level than the Inferior Oolite at the edge of the plateau.

The great result, then, of the disturbance and denudation of the Paleozoic strata, and of the

lesser disturbance and denudation of the Secondary rocks, is,

[324 North of England.]

that the physical features of England and Wales present masses of Palæozoic rocks, forming

groups of mountains in the west, then certain plains and undulating grounds composed of New

Red Sandstone, Marl, and Lias, and then two great escarpments, the edges of tablelands, which

rise in some places to a height of more than a thousand feet: the western one being formed of

Oolitic, and the eastern of Cretaceous strata, which, in its turn, is overlaid by the Eocene series

of the London and Hampshire basins. See fig. 57.

If we now turn to the north, what do we find there?

Through the centre of this part of England a great tract of Paleozoic country, more than 200

miles in length, stretches from the southern part of Derbyshire to the borders of Scotland, and

joins with the hilly ground of Berwickshire. It consists of Carboniferous rocks, ranging from

the Carboniferous Limestone up to those that pass beneath the base of the Permian strata.

Further west, between Morecambe Bay and the Solway, lie the Silurian and Carboniferous rocks

of the Cumbrian area, separated from the Carboniferous formations of Northumberland,

Durham, and Yorkshire, by the Peran beds of the Vale of Eden.

As far as the north borders of the Lancashire and Yorkshire coal-fields, the Carboniferous

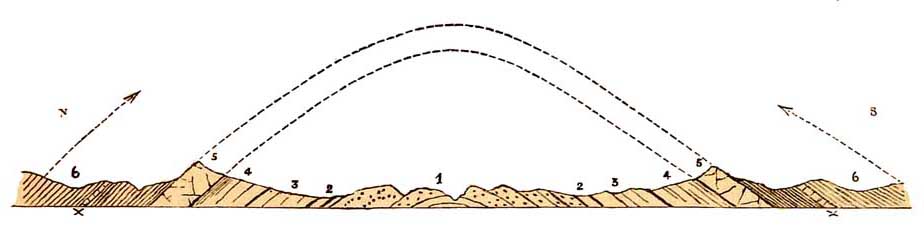

rocks lie in the form of a broad anticlinal curve.

At the southern end of this area a wide tract of Carboniferous Limestone hills ranging up to

1,200 feet in height, occupies the centre of the anticlinal curve, on each side of which, the

Yoredale shales and thick strata of Millstone grit dip east and west as the case may be. The

latter, being interstratified with comparatively soft beds of shale, run in long bold escarpments

(fig. 63), that often trend north and south both on the west and east sides

[324]

FIG. 63

Section, across the Carboniferous Rocks of Derbyshire and Lancashire.

Section, across the Carboniferous Rocks of Derbyshire and Lancashire.

1. Carb. Limestone forming the hilly centre of the anticlinal curve. 2. Yoredale shales, soft, and

forming valleys of denudation. 3. Terraced escarpments of hard sandstones, Mill stone grit. 4.

Coal-measures, consisting of softer rocks generally, forming a lower undulating country. 5.

Escarpment of Magnesian Limestone (Permian) overlaid by 6, New Red Sandstone.

[326 High Peak.]

of the Carboniferous Limestone, fine examples of which may be seen in the country near

Chatsworth on the east, and between Chapel-le-Frith, Buxton, and Hartington, and the

neighbourhood of Leek, on the west. Let anyone get to the highest limestone hills in the midst of

the area, and look west to Ax Edge beyond Buxton, and east towards Rowseley or Bakewell, and he

will see these escarpments, the nearest on either side, being generally separated from the

limestone hills by a deep valley excavated in the soft Yoredale shales. This special piece of

geological anatomy is, indeed, characteristic of the whole of the region, the limestone hills being

almost entirely surrounded by a valley, or valleys, the chief watershed of which is near

Castleton on the north, beyond which, on the east, the Derwent flows, well wooded, and still

often bordered by oaks,1 while on the west the classic Dove runs down a similar valley, till it

enters that gorge of tall limestone cliffs, which itself has cut some miles above Ashbourne.

Narrow dry dales are common in the Carboniferous Limestone region, and probably some of

these are the relics of old underground watercourses, the roofs of which have fallen in.

In the northern part of Derbyshire, near Hathersage and the High Peak, the Millstone grit lies

in broad plateaux, often from 1,000 to 1,200 feet in height. Great part of the country, east

towards Derwent Dale and north of the High Peak, is called the Woodlands. In places the steep

hill-sides are still dotted with little woods and single trees of birch, ash, mountain ash, oak,

and elder, the relics of the forest that once gave this high country its name.

1

Derwyn is Welsh for an oak, whence probably the original name of the river.

[Kinder Scout. 327]

If from the Snake Inn on the Glossop road you climb the High Peak, or, as it is often called,

Kinder Scout, taking Fairbrook as your route, you first pass across shales with beds of Yoredale

grit, over which the water falls in tiny cascades, and at length, high on the top, the view is

barred by a great cliff of rock running in a sinuous line to right and left. It consists of coarse

quartzose sandstone, covered in great part by about 12 feet of peat, which in all directions is

intersected by devious steep-sided water-worn channels, among which, in trying to work out a

straight course, you are apt to return to the point from whence you started. If you could from a

balloon look down upon it, it would

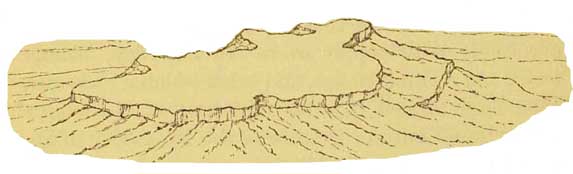

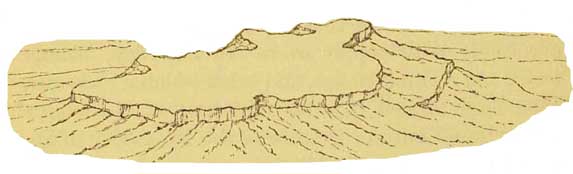

FIG. 64.

look somewhat as in fig. 64, its whole length being about 6 miles by 2 in breadth. This is the

character of the country. Kinder Scout is in the centre of a long, low, anticlinal curve, and the

strata lie nearly flat, while to the right and left the equivalent strata form definite scarps,

dipping in opposite directions.

Where bare of peat, the surface

of this little tableland is marked by numerous monumentallooking pillars

of stone, sometimes undercut, which helps to show how high flat areas of

such rocks are worn away by ordinary atmospheric agents. Some of these have

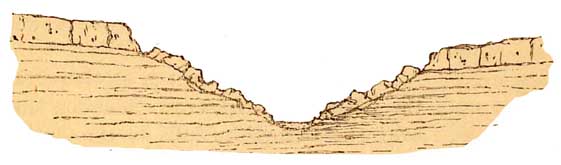

such forms as in the following diagram, fig. 65, and I

[328 Landslips.]

give them to show that even on the top of the table-land, where of running water there is almost

none, degradation and lowering of the surface does not absolutely

FIG. 65.

cease. This work is aided by the easy decomposition of the feispar, which forms an important

ingredient in this coarse-grained sandstone, and during heavy gales that sweep across the high

bare plateau, the sand is driven along the surface, and grating along the bases of the projecting

masses of rock, these become undercut, and eventually must topple over. In this way, Brimham

rocks, and rocking-stones, and other isolated rock-masses have been formed in other districts,

as, for example, such a grand mass of granite as the Mainstone of Dartmoor, now unhappily

blasted away and sold by its proprietor.

There is no area that shows

better than this part of Derbyshire how valleys have been formed in a high

tableland composed of Carboniferous sandstones and shales. There are landslips

everywhere. Going up the valley from Hathersage a notable landslip is to

be seen on the hill-side west of the Derwent and south of Yorkshire Bridge.

Between that and the twenty-fifth milestone, on the road to Glossop, there

are several on either side of the valley. On the north side of the valley

of the Ashop, the shattered masses cumber the hill-side for at least three

miles, and on the east side of Alport Dale, there is one vast landslip a

mile in length. The whole hill-side

[Landslips and Valleys. 329]

side has slipped bodily away, part lies in tumbled ruins all the way down to the river, and part

still stands in tower-like peaks and solid flat-topped castlelike masses, called Alport towers

and Alport castles.

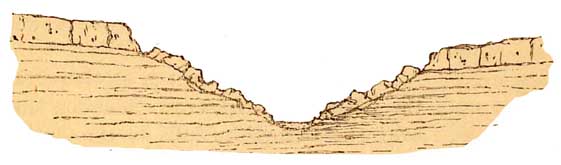

This is the law of waste in such cases:—

FIG. 66.

The upper strata of the tableland consists of thick beds of sandstone, much jointed, and easily

permeated by rain-water; the shale beneath becomes softened and

slippery, and great masses of sandstone slip over the brow, and, once there, by gravity find their

way to the bottom of the valley. Just in proportion as the river attacks and carries away the

crumbling ruins below, the upper part of the slip gradually creeps down the slope, till at length

it reaches the river. Thus repeated slips take place on one or both sides of the valley, and though

the river is always deepening its channel, the waste from the hill-sides, by slips and

rainwaste, is proportionate to the average deepening, and thus the valley goes on increasing both

in depth and width.1

It requires little imagination to divine how such valleys began to be formed by streams running

in slight inequalities on the very top of the sandstone plateau, till at length, channels being cut

through the sandstones,

1

These and many other valleys are also deepened and. widened

by the process described at pp. 533-36 in regard to the Moselle, &c.

[330 Mountains, Plains, and Escarpments.]

landslips came in aid, and are still in progress. This general description, with local variations

dependent on lithological variations, and the dips, strikes, and faults of the strata, may serve

for much of the Carboniferous ground in the middle of the anticlinal curve, as far as the northern borders of the Yorkshire and Lancashire coal-fields.

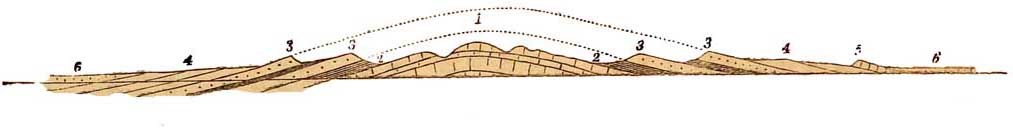

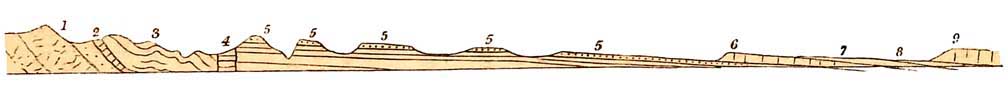

FIG. 67.

Section from Snowdon to the east of England.

If we now construct a section from

the Menai Straits, across Snowdon and over the Derbyshire hills to the east of England, the

arrangement of the strata may be typified in the following manner (fig. 67, and Map, line 17).

In the west, rise the older disturbed Silurian strata, Nos. 1 to 3, which form the mountan region of Wales. On the east of these lies an upper portion

of the Palæozoic rocks, 4, consisting of Carboniferous beds with an escarpment facing west. They are less disturbed than the underlying Silurian

strata on which they lie unconformably. Then, in Cheshire, to the east of

the Dee, lie the great undulating plains of the New Red series, 6, and these

form plains because they consist of strata that have never been much disturbed

and still lie nearly flat, and are soft and easily denuded, whence, in part,

the soft rolling undulations of the scenery. Then more easterly, from under

the strata of New Red Sandstone, the disturbed Coal-measures again rise, together

with the

[Mountains, Plains, and Escarpments. 331]

Millstone Grit and Carboniferous Limestone forming the Derbyshire hills, 4'. These strata dip

first to the west, underneath the New Red Sandstone, and then roll over to the east, forming an

anticinal curve, the Limestone being in the centre, and the Millstone Grit on both sides dipping

west and east; and above the Millstone Grit come the Coal-measures, also dipping west and east.

Together they form the southern part of the Pennine chain. Upon the Coal-measures in

Nottinghamsbire, Derbyshire, and Yorkshire, dipping easterly at low angles, we have, first, a

low escarpment of Magnesian Limestone 5, then the New Red Sandstone and Lias plains 6 and 7,

which are covered to the east by the Oolite 9, forming a low escarpment, the latter being

overlaid by that of the Chalk 11. In this district, except in North Yorkshire, the Oolitic strata,

being thinner, do not form the same bold scarped tableland that they do in Gloucestershire and

the more southern parts of England. As shown in the diagram the Cretaceous rocks also rise in a

tolerably marked escarpment.

Further north the grand general features are as follows:—If a section were drawn across England

from the Cumberland mountains south-easterly to Bridlington Bay, the following diagram, fig.

68, will explain the general arrangement of the strata, and the effect of this on the physical

geography of the district.

On the west there are the Green Slates and porphyries, No. 1, consisting of lavas and volcanic

ashes, hard but of unequal hardness, and some of them, therefore, by help of denudation giving

specialities of form to some of the loftiest mountains of Cumberland. Then comes 2, the Coniston

Limestone, overlaid by Upper Silurian rocks, 3, forming a hilly country, between which

[332]

FIG. 68.

Section from Cumberland towards Bridlington.

Section from Cumberland towards Bridlington.

1. Igneous rocks or Green Slates and Porphyrys (lavas and volcanic ashes) of Lower Silurian

age. 2. Coniston Limestone. 3. Upper Silurian grit, &c. 4. Carboniferous Limestone, between

faults. 5. Yoredale rocks and Millstone grit. 6. Magnesian Limestone. 7. New Red strata. 8. Lias.

9. Chalk.

Plains. 333

and the Carboniferous grits, 5, lies the Carboniferous Limestone between two faults in a broken

country. Then comes a marked feature in the district, consisting of the long, gently sloping beds

of Yoredale rocks and Millstone Grit, No. 5, dipping easterly till they slip out of sight beneath

the Magnesian Limestone, No. 6, overlaid in succession by New Red beds and Lias plains, 7 and

8, which are overlooked by an escarpment of Chalk, 9. This Chalk is overlaid by Boulder-clay,

the eastern edge of which forms a cliff overlooking the sea.

North of this region, till we come to the east side of the Vale of Eden, the country is much

complicated by faults and other disturbances, and to describe it in detail would occupy much

space, but east of the Vale of Eden the structure of the country is again exceedingly simple, the

whole of the Carboniferous rocks dipping steadily east at low angles, all the way from the

escarpment that overlooks the vale, to the German Ocean that borders the Northumberland coalfield, fig. 69, p. 334.

While travelling northward from London by the Great Northern Railway, many persons must be

struck with the general flatness of the country after passing the Cretaceous escarpments north

of Hitchin. Before reaching Peterborough the line enters on the great peaty and alluvial flats

of Cambridgeshire, Lincolnshire, and the Wash, a vast plain, and once a great bay, formed by

the denudation of the Kimeridge and Oxford Clays. It has been for long the recipient of the mud of

several rivers—the Ouse, the Nen, the Welland, the Witham, and the Glen. Nature and art have

combined, by silting and by dykes, to turn the flat into a miniature Holland, about 70 miles in

length and 36 in width. Near Stamford, passing through the low, flat-topped undulations of the

Oolitic and Lias, with

[334 Yorkshire Hills.]

their minor escarpments facing west, the railway emerges, after crossing the Trent, on a

second plain, through which, swelled by many tributaries—the Idle, the Don, the Calder, the

Aire, the Wharfe, the Nidd, the Ure, the Swale, and the Derwent—the Trent and the Ouse flow to enter the famous

estuary of the Humber.

FIG. 69.

Passing north by York the same plain forms the bottom of the low broad valley that lies between

the westward rising dip-slopes of the Millstone Grit, &c., and the bold escarpment of the

Yorkshire Oolites on the east, till at length it passes out to sea on either side of the estuary of

the Tees. The adjoining diagram represents the general structure of the region on a line from

Ingleborough on the west to the Oolitic moors.

On the west lie the outlying heights of the ancient camp of Ingleborough, and of Penyghent,

capped with Millstone Grit and Yoredale rocks (2), which, intersected by valleys, gradually dip

eastward, the

average slope of the ground over long areas often corresponding with the dip of the strata in the manner shown in the diagram,1

till they slip under the low escarpment of Magnesian Limestone (3).

Let the reader attentively consider this part of the diagram, and he may I hope convince himself how little ordinary valleys,

large or small, are directly

1

This kind of slope is often called a dip-slope.

[Yorkshire Plains. 335]

produced by fractures and 'convulsions of Nature,' for in this and many similar cases, what can be

their origin but the tranquil scooping powers of disintegration and running water, aided by an

unknown amount of time. East of the Magnesian Limestone lies the plain (p), almost as flat as a

table, and covered to a great extent with an oozy loam, like the warps of the Wash and the

Humber, and like these, perhaps, formed of old river sediments. The New Red and Lower Lias

strata (4) lie beneath the warp, and for the most part, below the level of the sea, and high on

the east, like a great rampart, the escarpment of the Oolites (5) rises in places to a height of

more than 1,100 feet, with all its broad-topped moorlands and deep well-wooded valleys. Such

is the anatomy of the fertile Vale of York and its neighbourhood.