[372]

CHAPTER XXIV.

OLD BRITISH GLACIERS.

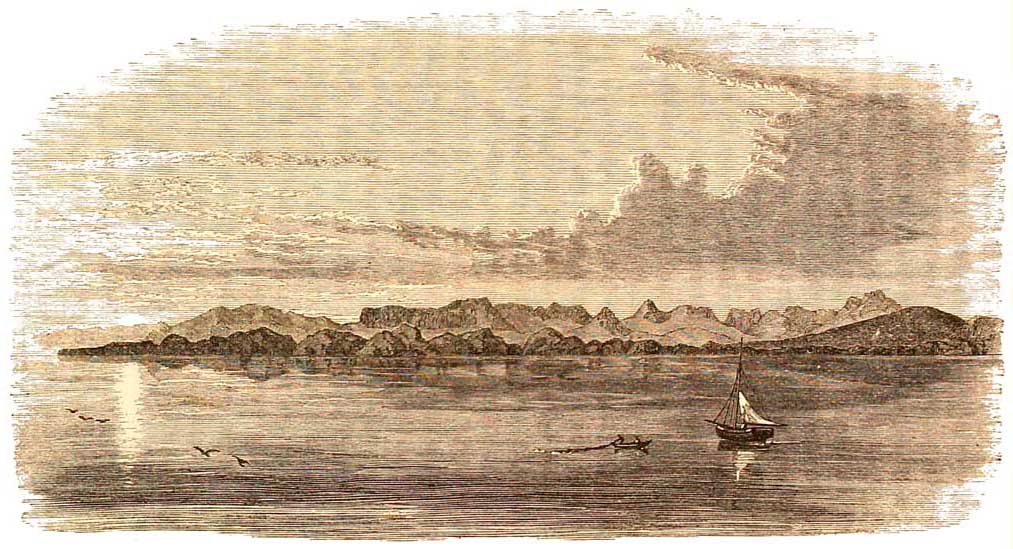

THOSE who have closely observed the Highlands of Scotland and of Cumberland, may remember

that, though the weather has had a powerful influence, rendering the mountains in places

rugged, jagged, and cliffy, yet, notwithstanding this, their general outlines are often

remarkably rounded, flowing in great and small mammillated curves, a configuration of ground

tolerably plain in the accompanying view (fig. 80), especially in the rocks of the island in the

foreground. When we examine the valleys and plains in detail we also find that the same

mammillated structure frequently prevails. These rounded forms are known in Switzerland as

roches moutonnées, a name now in general use among those who study the action of glacier-ice.

Similar icesmoothed rocks strike the eye in many British valleys, marked by the same kind of

grooving and striation, so characteristic of the rocks of Switzerland. Almost every valley in the

Highlands of Scotland bears them, and the same is the case in Cumberland, Wales, and other

districts in the British Islands, and not in the valleys alone, but also in the low countries as far

as Liverpool and the middle of England.

Considering all these things, geologists, led many years ago by Agassiz, have by degrees come to

the

[373]

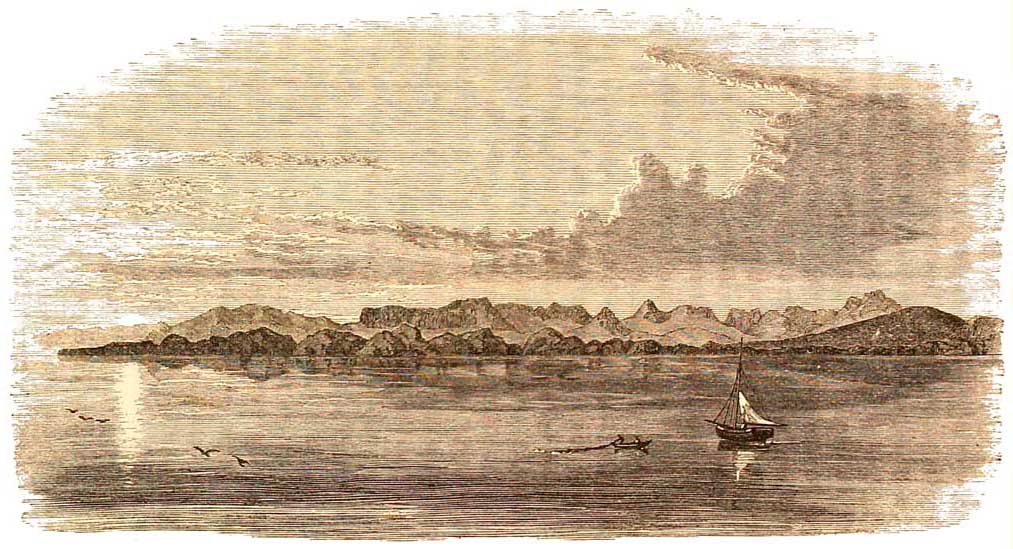

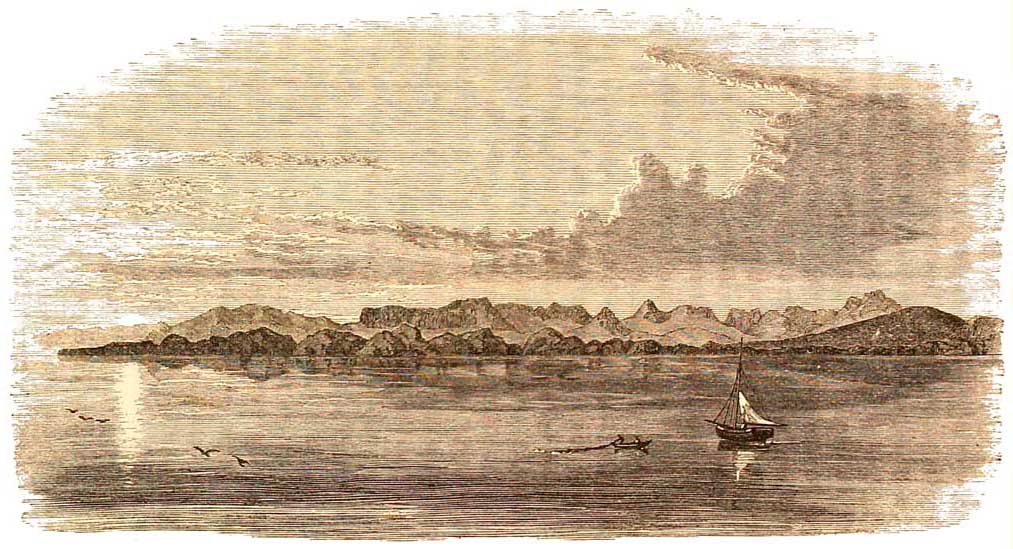

FIG. 79.

Mountains of Ross-shire, with the Island of Rona in front.

[374 Old British and]

conclusion that large parts of the northern hemisphere were, during the 'glacial period,' more

or less covered, or nearly covered, with a coating of thick ice, in the same way that the greater

parts of Greenland, Spitzbergen, and the whole of Victoria Land are covered at present. Britain

formed part of this area, and, by the long-continued grinding power of great glaciers nearly

universal over the northern half of our country and Wales, the whole surface became moulded

by ice. The relics of this action still remain strongly impressed on this country to attest its

former power, and I need scarcely say that the same kind of phenomena are equally striking in

Ireland.

It might be unsafe to form this conclusion merely by an examination of such a small tract of

country as the British Islands, but when we consider the great Scandinavian chain, and the

northern half of Europe generally, we find that similar phenomena are common over the whole

of that area, and in the North American Continent, as far south as latitude 38° or 40°; for when

the soil, or the superficial covering of other debris is removed, we discover over large areas

that the solid rock is smoothed and polished, and covered with grooves and striations, similar to

those of which we have experience among the glaciers of the Alps. I do not speak merely by

common report in this matter, for I know it from personal observation, both in the Old

Continent and the New. We know of no power on earth, of a natural kind, which produces these

indications except moving ice, and therefore geologists are justified in attributing them, even

on this great continental scale, to ice-action.

This conclusion is fortified by many other circumstances. Thus, I have stated that in the Alps

there is

[Other Glaciers. 375]

evidence that the present glaciers were once on an immensely larger scale than at present. The

proof not only lies in the polished and grooved rocks far removed from the actual glaciers of the

present day, but also in numerous moraines on a scale so immense that the largest now forming

in the Alps are of pigmy size when compared with them. Such a moraine is the great one of the

Dora Baltea, sometimes called the Moraine of Ivrea, which, on the plains outside the mouth of

the Val d'Aosta, encloses a circuit of about sixty miles, and rises above the plain more than

1,600 feet in height, being altogether formed of mere accumulations of moraine rubbish. Its

width in places averages about seven miles, as mapped by Gastaldi. Many others might be cited.

The same kind of phenomena occur in the Altai Mountains, the Himalayah, the Caucasus, the

Rocky Mountains, the Andes, the Sierra Nevada, and the Pyrenees of Spain, the Atlas of Morocco,

the mountains of Sweden and Norway, the Black Forest and the Vosges, and in many other

northern mountain chains or clusters, great or small, that have been critically examined. In the

southern hemisphere, where mountain ranges are comparatively scarce, the same ancient

extension of glaciers is prominent in New Zealand. Therefore there can be no doubt that at late

periods of the world's history a climate or climates prevailed over large tracts of the earth's

surface generally, but not always, of extreme arctic severity, for there were intermittent

episodes of comparative warmth, when what is misnamed perpetual snow disappeared, or almost

disappeared from mountain regions of moderate height. The cold of these minor cycles in time

(for as shown by Dr. Croll, glacial cycles alternate in the northern and southern hemispheres)

was produced by causes about which there have

[376 Cause of Glacial Epochs.]

been many guesses, and which, perhaps, are only now beginning to be understood.

It is not very many years, since a great difference in the geographical distribution of land and

sea was regarded as a possible or even a probable cause of the occurrence of important changes

of climate during Geological Time. If, said Lyell, in his earlier writings, all the continental

lands, were gathered in tropical regions, and the rest of the globe were mainly covered by sea,

the climates of the world would he tropical and temperate according to their latitudes, and if all

the land were mainly massed round the poles, even in the tropics there would be no tropical heat

such as they now endure, while the greater portions of the northern and southern hemispheres

would suffer from climates of extreme severity. In such a sketch as this it is needless to argue

the question, at all events as regards this special glacial epoch, for the obvious reason that it is

an established fact that during most of that epoch, the continents of the world, mountain chains

and all, were distributed much as they are at present, with occasional minor variations in detail

due to short local submergences.

Neither is it worth while to discuss the facile explanation of variation of climate, being due to

the sun with all its planets travelling through alternate hot and cold regions of space. Such an

idea crops out now and then in conversation, but I do not remember to have met any educated

physicist who seriously entertained it.

I believe that the day may come, when both astronomers and geologists will be forced to allow

that, in great cycles of geological time, changes have taken place in the position of the earth's

axis of rotation, in a slowly cumulative manner, by gradual disturbances of

[Cause of Glacial Epochs. 377]

what is called the crust of the earth, but by no means by sudden upheavals of vast mountain

tracts at or near the poles, or anywhere else on the earth's surface; and, indeed, the phenomena

of the vegetation of old geological epochs in formations as far north as land has been discovered,

seems to me to point in that direction and in no other. At all events it is plain, that no such

sweeping changes of physical geography have taken place in those comparatively short episodes

of geological history, that have graduated into, each other from the beginning of this latest

glacial epoch down to the present day, and therefore it is needless to discuss the question here.

There is, however, an astronomical cause which seems to meet all the circumstances of any one

glacial epoch, and is therefore deserving of the gravest attention. The question has been worked

out with great skill by Dr. James Croll, first, in various memoirs, and latterly, in his

celebrated work 'Climate and Time,' and I can only state in a very sketchy manner some of his

main conclusions.

Alternations of cold and warm or temperate climates, in the same latitudes, are in the first

instance due to the varying eccentricity of the orbit of the earth, by which 'a host of physical

agencies are brought into operation, the combined effect of which is to lower to a very great

extent the temperature of the hemisphere whose winters occur in apheliou, and to raise to

nearly as great an extent the temperature of the opposite hemisphere, whose winters of course

occur in perihelion.' It is perhaps possible that the orbit of the Earth may become circular, at

periods of time prodigiously far removed from each other, but at present, when the earth in its

elliptical orbit is

[378 Cause of Glacial Epochs.]

furthest from the sun (aphelion), the distance is about 90 millions of miles, and its smallest

distance (perihelion) is about 89,864,480 miles. The varying amount of ellipticity is owing to

the ever-changing positions of the planets in our solar system within and without the orbit of

rotation of the earth, and we can imagine a state of combination of the planets, the effect of the

attraction of which must be to lengthen the ellipse in the extremest possible degree, so that the

earth in aphelion would be 98 1/2 millions of miles distant from the sun. This is not a mere guess,

for it has been approximately calculated by Leverrier and other astronomers. The eccentricity

of the earth's orbit is at present decreasing, and it will reach its minimum in about 24,000

years.

In connection with degrees

of eccentricity, Dr. Croll argues that the distribution of ocean-currents

is due to the system of winds, and in the modern world the existing system

of winds is due to those astronomical causes that, by help of eccentricity

have produced a minor glacial epoch in part of the southern hemisphere at

the present day, and a remarkably mild one over Western Europe and great

part of the north. This coincidence of winds and great ocean currents is

shown by Dr. Croll in a map, the most familiar of which to us, being the

westerly and southwesterly winds and currents of the Gulf Stream, the warm

winds from which so largely raise the average temperature of the British

Islands and the whole of the western part of Europe. There being nothing

equivalent to this current running south towards the great Antartic Continent

of Victoria Land, this circumstance, taken in connection with the fact that

the southern winter occurs in aphelion, has produced in that region a minor

glacial epoch, so that in south latitudes, between about 64° and 78°, the

[Cause of Glacial Epochs. 379]

whole country is nearly entirely shrouded in glacier-ice, and is altogether uninhabitable by

man, while in the northern hemisphere, in equivalent latitudes, there are no parts of North

America and Europe totally uninhabited, and even the north of Norway in summer, when the sun

does not set, is often inconveniently warm, and the traveller is troubled with clouds of

mosquitoes.

The present winter of the southern hemisphere being when the earth is in aphelion, the result

is this, that the winter of the Antipodes is seven or eight days longer than our own, for the

further the earth is removed from the sun, the more slowly it moves in its orbit, and the

nearer it is, it moves in proportion more rapidly, and this somewhat lengthened winter,

coupled with the absence of heated water flowing south from equatorial regions, has enabled the

snows to accumulate, and being but little affected even by the summer's sun, the country is

continually buried in ice, while in Norway and on the shores of the Baltic, in equivalent

latitudes, forests, grass, and crops abound. The winter of our northern hemisphere is of course

seven or eight days shorter than that of the south, and the earth is at that season with us nearest

to the sun, and our summer being a little longer though further from the sun, the effect of its

heat corresponds to the difference, irrespective of the powerful effect of the heated water of the

Gulf Stream.

If such marked results are produced with this comparatively small amount of eccentricity, it is

reasonable to suppose that with the greatest possible eccentricity the effect must be much

greater, and it has been calculated that when this by slow degrees takes place, the earth in

aphelion is distant from the sun about 98 1/2 millions of miles, or nearly 7 millions of miles

further

[380 Glacial Epoch in Britain.]

from the sun than when eccentricity is at a minimum, or about 8 1/2 millions further than its

greatest distance now. The earth, therefore, in aphelion would be more than 14 millions of

miles farther from the sun than when in perihelion, and if, in accordance with the precession of

the equinoxes, it so happened that winter in the northern hemisphere took place when the earth

is furthest from the sun, then by calculation it has been shown that 'the direct heat of the sun in

winter would be one-fifth less during that season than at present, and in summer one-fifth

greater.' But this extra amount of heat in summer would even less have sufficed to remove the

snow and ice then, than it suffices to remove it from Victoria Land at the present day; for just as

that region is all summer apt to be involved in clouds and fogs by vapours, due to partial

evaporation of melting snow, even so on a greater scale the same effect must have been produced

in old epochs, when greater glacial epochs took place alternately in the northern and southern

hemispheres.

It was during part, or in parts of one of these periods, that great part of what is now the British

Islands, was last almost entirely covered with ice, for, as I have already shown, similar

phenomena are periodical, and have occurred in several old geological epochs. I do not say that

our area consisted of islands during the whole of the last Glacial epoch, and probably during part

of it they were united with the Continent, and the average level of the land may then have been

somewhat higher than at present, by elevation of the whole, and also because since the first

appearance of British glaciers it has suffered much degradation; but whether this was so or not,

the mountains and much of the lowlands were long covered with a universal coating of ice,

[381]

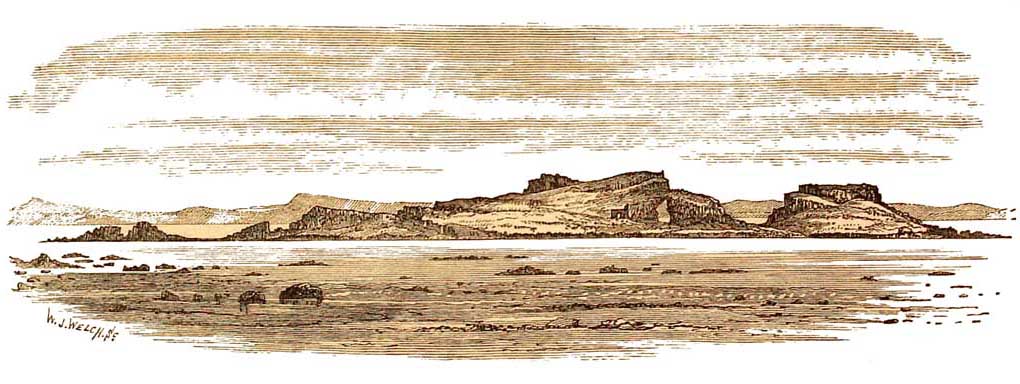

FIG. 80.

Fidra Island, North Berwick, Firth of Forth.

Fidra Island, North Berwick, Firth of Forth.

[382 Glacial Epoch in Britain.]

probably as thick as that in the north of Greenland in the present day. During this time all the

Highland mountains were literally buried in ice, which, partly flowing eastward, joined a vast

ice-sheet coming westerly and southerly from Scandinavia. In another direction a thick sheet of

the same Highland ice pressed southward into the valley of the Tay, where a low stratum of the

glacier passed eastward to the sea, while the remainder pressed up the slopes and across the

summits of the Ochil Hills, and on to the valley of the Forth, where it found a vent for a further

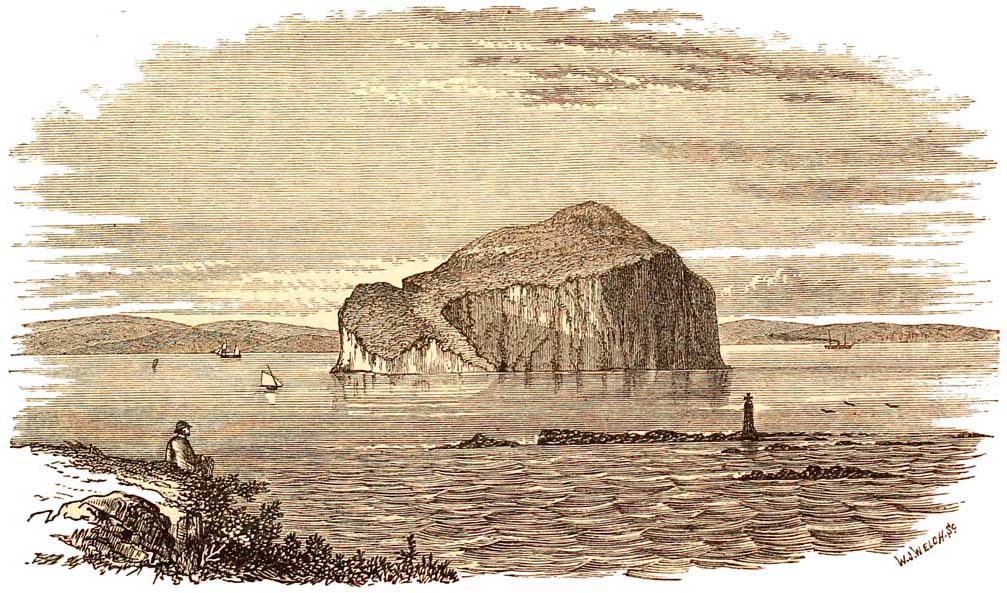

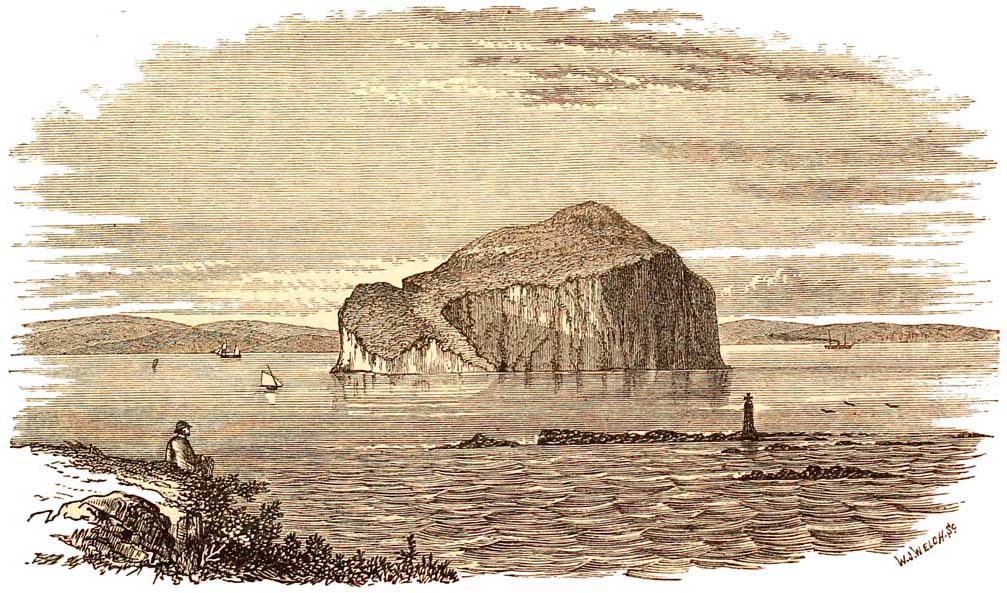

outflow to the east, at a time when the Bass Rock, Fidra Island, Inch Keith, Inch Colon, and all

the other beautiful islands of tbe Firth of Forth, lay as mere roches moutonnées, buried so deep

under glacier-ice that it overflowed the eastern part of the Lammermuirs and spread southward

into Northumberland. Some of these islands still retain their ice-worn surfaces, while others,

such as the Bass and Fidra, have become scarred and cliffy by the action of weather and the sea

(figs. 80 and 81). Another part of the great glacier-ice passed west across the Hebrides, and

southerly into the Firth of Clyde, where, passing over Bute, and smothering and smoothing those

large mammillations the Cumbraes, it was reinforced by the snows of Arran, and buried that

'craggy ocean pyramid,' Ailsa Craig. All the southern Highlands, from Fast Castle on the east to

Wigtonshire on the west coast, were also covered with glacier ice, together with

Northumberland, Durham, and the beautiful dales of Yorkshire, scooped out of the

Carboniferous series of rocks. Cumberland too was buried in ice, part of which crossed the vale

of Eden and over the hills beyond, carrying detritus to the eastern shore of England. So great was

this ice-sheet that, joining with the ice-stream

[383]

FIG. 81.

Bass Rock, Firth of Forth.

[384 Glacial Epochs.]

coming from what is now the basin of the Clyde, it stretched away south so far that it

overflowed Anglesea, and, so to speak, overcame the force of the smaller tributary glaciers that

descended from the mountains of North Wales; for the glacial striations of Anglesea point not to

the Snowdonian range, but about 25° to 30° east of north, directly toward the mountains of

Cumberland. South of Wales, in England, I know of no definite signs of the direct action of

glaciers.

Much of the Lower Boulder-clay is known as 'Till ' in Scotland; and it was only by slow degrees

that geologists became reconciled to the idea that this Till is nothing but moraine rubbish on a

vast scale, formed by those old glaciers that once covered the northern part of our country. In

fact, Agassiz, who held these views, and Buckland who followed him, were something like twenty

years before their time; and men sought to explain the phenomena of this universal glaciation

by every method but the true one. Mr. Robert Chambers was, I think, the first after Agassiz who

asserted that Scotland had been nearly covered by glacier ice, and now the subject is being

worked out in all its details, thus coming back to the old generalised hypothesis of Agassiz,

which is now accepted by many of the best geologists of Europe and America.

The general result has been

that the whole of the regions of Britain mentioned1 have literally been moulded by ice, that is to say, the country in many parts was so much ground

by glacieraction, on a continental scale, that though in later times it has

been more or less scarred by weather, enough remains of the effects to tell

to the observant eye the greatness of the

1 And equivalent regions in Ireland which in this book it is not my object to describe.

[Boulder-Clay. 385]

power of moving ice. Suddenly strip Greenland of its ice-sheet, and it will present a picture,

something like the greater part of Britain immediately after the close of this Glacial period.

During the time that these results were being produced by glacial action, there were occasional

important oscillations in temperature, so that the ice sometimes increased and sometimes

diminished, and land animals that lived habitually outside the great glacier limits, at intervals

advanced north or retreated south with the retreating or advancing ice.

Evidence of the same kind is not wanting in England, for erratic stones and large blocks of

granite, gneiss, felspathic traps, Carboniferous Limestone, &c. are scattered over the west and

east coasts and the central counties of England. Boulders of Shap granite of Cumberland are

common in Staffordshire, and even in the valley of the Severn, about twelve miles north of

Cheltenham, and they have also been borne across the central watershed of the north into the

plains of Yorkshire, near Darlington, and further south on the banks of the Humber. This

distribution of erratic stones, on the east of England, throws much light on the subject of the

motion of large sheets of glacier-ice, and therefore it is worth while to give a few details, some

of which are probably not generally known.1

At and a little south of Berwick-upon-Tweed,

where the sea-cliffs are clear, or, when the Till has been re moved, the

surfaces of quarries of Carboniferous Limestone are found to be icepolished

and grooved, the striations point from 10° to 12° south of east, in the

1 The observations were made in 1863 during an examination of the glacial accumulations on the

coast-cliffs by Professor J. Geikie, Mr. Aveline, and myself, and are extracted from my notebook.

[386 Glacial Epoch.]

direction, in fact, of the onward march of the vast glacier that flowed from the Highland

mountains down the valley of the Forth, and overflowing the Lammermuir Hills, spread across

the border into England. The stones in the Till are scratched, and consist of Carboniferous

Limestone (very angular at the base of the Till) and of other materials derived from the

northern hills. Some of the boulders are from one to two yards in diameter, and the beach-like

sands and gravels that overlie the Till are charged with large blocks of limestone and porphyry

at the base, and many broken seashells. In places these sands are strangely contorted, as if they

had been disturbed and pushed on by moving ice. The large blocks in them are of the

Carboniferous Limestone of the country, and the smaller ones consist of what seems to be

Silurian Lammermuir grit, granite, probably from the same area, and felspathic and augitic porphyries, &c.

About ten miles further south, near Belford, the glacial striations trend about 15° south of east,

and still point towards the upper part of the estuary of the Forth, and much of the low ground

round Belford and Lucker is formed of those singular mounds, called Kames in Scotland, and

Eskirs in Ireland, beautiful examples of which are known to many persons at Carstairs and

Carnwath in Lanarkshire, near Stranraer in Wigtonshire, and in many other areas in Scotland.1

So identical are the phenomena, that in my note-book I find that I compare the English examples

with those of Carstairs and Carnwath, and like the existing lakes and pools in these, the Kames

of Belford and Lucker in older times

1 For details respecting Scottish Kames, see 'Great, Ice Age,' J. Geikie, chapter xix.

[Boulder-Clay. 387]

held lakes and tarns in the hollows of the mounds, but now filled with peat.

On the coast near Alnmouth, in Northumberland, there is a large sand-bank overlooking the

river with intercalations of fine loamy clay. The sand contains fragments of coal and other

Carboniferous rocks, and in the middle of the sand there lies a lenticular patch of Boulder-clay,

from six to ten feet thick, full of angular ice-scratched stones confusedly mingled with the clay.

They consist of pieces of Carboniferous Limestone, porphyries, sandstone, &c. the largest being

about a foot in diameter.

Some miles south of Blyth there

h a cliff forming a promontory on the coast, made of boulderclays, near Seaton.

It consists of two divisions, rarely separated by thin lenticular bands of

sand. The lower band of greyish-blue clay is charged with large boulders,

while in the upper one, which is of a brown colour, the stones are much smaller.

The lower boulder-clay seems to belong to the great glacier period that produced

the Till, and the upper band to a later glacial episode, and except in the

parting of sand, there are no signs of true stratification. The large blocks,

which are very numerous, chiefly consist of Carboniferous sandstone and conglomerate,

which are often from one to two yards in diameter. Blocks of Carboniferous

Limestone are fewer in number, as might be expected, for the Boulder-clay

lies on Coal-measures, while the Limestone occurs more than twenty miles

to the north and northwest. Mingled with these are fragments of granite and

greenstone.

On both banks of the Tyne, above Newcastle, there are great banks of sand, gravel, and tilly

clay, all charged with ice-scratched stones of no great size. They

[388 Glacial Epoch.]

consist of Coal-measure sandstones and conglomerate, Carboniferous Limestone, and more

sparingly, Lammermuir grits and granite. In pits thirty feet in depth, beneath sands, the clay is

very fine, containing a few scratched stones, and we were informed that this clay has been sunk

through to a depth of fifty fathoms (300 feet), so that the bottom of this pre-glacial

rivervalley is much below the level of the sea.

Under Tynemouth, at the mouth of the river, there is a high cliff of stiff Boulder-clay, about 50

or 60 feet in height, facing North Shields. Stones and boulders large and small are scattered all

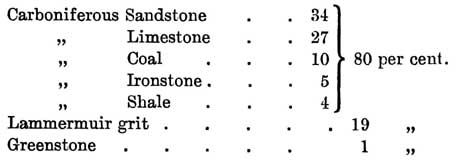

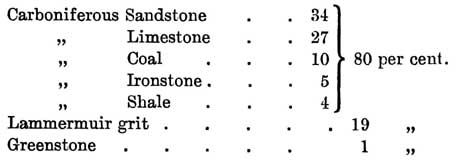

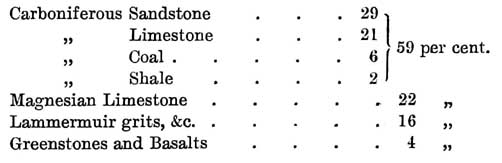

through the clay from bottom to top approximately in the following proportions:—

There are several irregular thin bands of gravel and sand in the Till. It will be observed that

excepting two insignificant outlying patches of Magnesian Limestone at Tynemouth, all the rocks

up to and beyond the borders of Scotland belong to the Carboniferous series, and the result is,

that of the ice-borne erratics, 80 per cent. belong to these formations, and only 19 per cent. to

the more distant Silurian grits of the Lammermuir range.

At Sunderland, about a mile north of the harbour light, there is a section of boulder-clay lying

on the Magnesian Limestone. The surface of this rock has been polished by glacier ice, and the

striations trend very nearly from north-east to south-west. The overlying

[Boulder-Clay. 389]

clay has the character of genuine Till, and the change in the direction of the striations

from those previously noticed, may possibly be due to the pressure of the inferred Scandinavian

ice-sheet, which is supposed to have united with that coming from Scotland, and may for a space

have deflected the line of its onward march from the NNW. On the other hand, it may be a mere

local accident connected with a later part of the Glacial epoch, when a distinct individual glacier

flowed from the far western watershed, more than a thousand feet in height, about the sources of

the Wear, which may have spread into a fan-shape as it reached what is now the shore. Such

smaller glaciers existed, for in these long dales of Durham and Yorkshire there are distinct

moraines, which mark the gradual decline of the glaciers, and through which, and through the

Boulder-clay, the rivers have cut their modern channels.

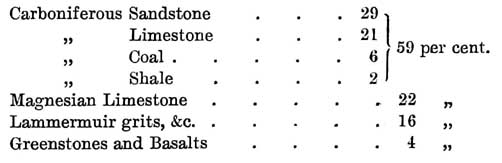

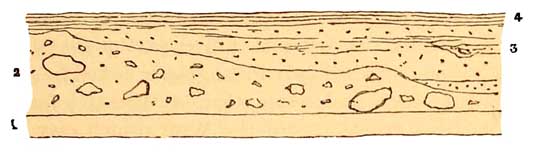

Stones derived from the Magnesian Limestone first appear in the Till south of Tynemouth. In the

neighbourhood of Sunderland, the percentage of various kinds of rocks seems to be nearly as

follows:—

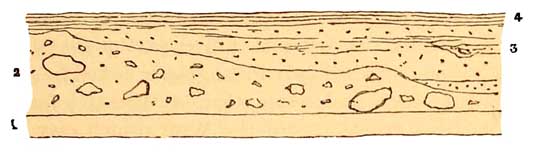

The cliff is about 30 feet in height, and shows the section given in fig. 82.

The Till seems to have been worn on the surface

before the deposition of 3 and 4.

It will be observed by consulting any geological

map, that, as in the previous case, the large percentages

[390 Glacial Epoch.]

of Carboniferous rocks have travelled from the widespread Carboniferous country to the north,

that the smaller percentage of Magnesian Limestone fragments must have been derived from the

small area immediately

FIG. 82.

1. Rotten nodular Magnesian Limestone.

2. Stiff brown Till with blocks and scratched stones. The largest are of Carboniferous Limestone

and Magnesian Limestone, from 1 to 1 1/2 yards in diameter, and 1 block 2 1/2 feet of Lammermuir

grit.

3. Sand and loamy beds with scratched stones, rare.

4. Finely laminated clay.

north of Sunderland, occupied by that formation for a distance of about 9 or 10 miles, and the

decreased proportion of Lammermuir rocks have had to travel not less than 70 miles.

Somewhat further south we find 57 per cent. of Carboniferous rocks, 32 per cent. of Magnesian

Limestone, and only 9 per cent. of Lammermuir grits.

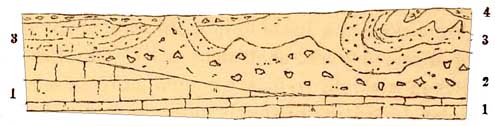

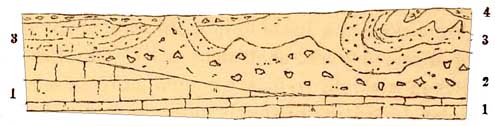

About half way between Sunderland and Seaham, where on a sea-cliff stiff Boulder-clay or Till

lies on the Magnesian Limestone, the latter is covered with glacial groovings which run from

NNW. to SSE. and all along the sea-cliffs of this neighbourhood there is a lower Boulder-clay

with a very irregular surface, on which there lies sand and gravel, often very much contorted,

which in its turn is overlaid by patches of an upper Boulder-clay.

[Boulder-Clay. 391]

At Seaham ironworks and elsewhere, such sands and

gravels in the middle of the Till frequently thin away in wedge-shaped ends.

FIG. 83.

1. Magnesian Limestone.

2. Lower Boulder-clay.

3. Sand and gravel.

4. Upper Boulder-clay.

It is unnecessary and would be wearisome to the reader, were I to describe all the details of the

sections I have examined between Hartlepool near the mouth of the Tees, and Spurn Point at the

mouth of the Humber. Suffice it to say that, in the Liassic and Oolitic region of Yorkshire, the

valleys that open upon the sea are apt to be more or less filled with boulder-clays, sands, and

gravels, and the same phenomena occur in many parts of the high sea-cliffs. Thus at Cromer

Point, about 2 1/2 miles north of Scarborough, there are beds of sand and gravel in places about

120 feet thick, which lie on an undulating surface of shales, &c., of the Oolitic series. The

embedded pebbles largely consist of sandstones (Oolitic in part), grits, porphyry, &c., and at

the top, about 130 feet above the sea, there are beds of clayey gravel with small stones and

fragments of seashells.

In Cayton Bay, about three

miles south of Scarborough, lying upon Oxford Clay, there is Boulder-clay,

with a great variety of boulders of Carboniferous Limestone, Lammermuir grit,

basalts, greenstones, and other rocks that lie nearer the spot. Many of

these are subangular and many are well rounded, and both kinds are

[392 Glacial Epoch.]

often marked with glacial scratchings. Above this Boulder-clay there are beds of gravel with

fragments of marine shells, and the embedded stones only show the ghosts of scratchings, as if

they had been nearly obliterated by trituration. Above this gravel, Boulder-clay again occurs in a

little hollow, in which there are deposits of fine clay and shell-marl, with Paludinas, &c. The

relics of such old pools are common on the surfaces of irregular deposition of the boulder-clays

all the way from Northumberland to the Humber, and doubtless far beyond.

On the coast, from one to two miles north of Bridlington, lying on chalk, there are beds of Till

interstratifled with beds of sand and gravel, parts of the Boulder-clay among the Till being much

contorted. In one case they were seen to lie in an old valley of erosion in the Chalk, the lowest

strata consisting of stratified brecciated chalk gravel, overlaid by sand, on which there rested

chalky sand and gravel, which in its turn is overlaid by Till with irregular minor

interstratifications of sand; and in another case, about three miles north of Bridlington,

fragments of sea-shells occur in the gravel about 150 feet above the sea. Near Bramston, in

Holderness, a few miles south of Bridlington, on the shore, there are large boulders of gneiss,

basalt, diorite, &c.

Immediately north of Hornsea, about twelve miles south of Bridlington, the Till, which partly

forms a seacliff fifty or sixty feet high, is very irregularly bedded, and contains numerous

scratched stones of flint and chalk, Carboniferous Limestone (more scarce), Silurian grit,

granite, gneiss, &c. The quantity of stones of chalk is quite a new and remarkable feature in the

section, for north of Flamborough Head, in the Oolitic country, I found none. The Till, which

forms the base

[Boulder-Clay. 393]

of one end of the cliff, is overlaid by sand and gravel, which again is overlaid by lenticular

patches of Till, covered by higher gravels, on which, in a hollow, there occur clays with

Paludinas deposited in an old freshwater pool. The same kinds of sections, with variations, are

found all the way from Hornsea to Withernsea and Spurn Point, and here and there many large

boulders of granite, Carboniferous and Lias Limestones, Sandstones with Stigmarias, &c., lie on

the shore, bearing witness to the recession of the cliff, which is fast wearing away under the

united influence of landslips, and the action of breakers and tides on the fallen masses of clay.

Nor do the remains of sea-shells cease, for at Out Newton, by the shore, the base of the cliff, in

which frequent landslips occur, consists of stiff blue Till with erratic blocks and many

fragmentary shells, overlaid by clay with smaller stones, on which lies well-stratified warp

clay, surmounted by beds of sea-sand and gravel, which again is overlaid by red Till with

scratched stones. On the shore of the Humber, also, when excavations were in progress

connected with the building of a fort, beds of sand, gravel, and warp were exposed, containing

sea-shells intensely contorted, as if the strata had been subjected to strong lateral pressure.

Between the Humber and the Wash I have no personal knowledge of the coast sections, which are

of the same general nature as those of Holderness. South and south-east of the Wash, as far as

the neighbourhood of the Thames, much has been written about glacial detritus, with the details

of which I will not now meddle. It is enough to state that by Mr. Searles Wood, junr. and Mr. F.

W. Harmer, they have been divided into Lower and Upper Boulder-clays, between which there

are beds of sand and gravel, often contorted,

[394 Glacial Epoch.]

thus presenting points of resemblance to the sections on the coast which I have described

between Berwick-on-Tweed and the mouth of the Humber. These sands and gravels which contain

sea-shells have been named by these gentlemen 'Middle Glacial.'

The Upper Glacial Boulder-clay

has been called by Mr. Wood and Mr. Skertchly the great Chalky Boulder-clay,

from the circumstance that it chiefly consists of chalk, ground up by an

advancing glacier travelling frcm north-east to south-west, the chalky and

flinty debris being sparingly mingled with fragments of Oolite, quartz, basalt,

granite, &c., sometimes smooth and striated. Though chiefly formed of

chalky material, yet when found lying on Kimeridge Clay it is found to be

mingled with the detritus of that formation, and when it reaches the Oxford

Clay, all three are intermingled. The Boulder-clay lying on each formation

that lay under the glacier icesheet, which was invading the country from

north to south, always partakes of the nature of the underlying rock, and

the total area occupied by this chalky Boulder-clay must, according to Mr.

Skertchly, have been more than 3,000 square miles in the south-east of England.

If, however, this supposed glacier extended as far south as Romford, where

there is Boulder-clay with scratched chalk-flints and masses of Oxford and

Kimeridge Clay, then the area covered by the great Chalky Boulder-clay and

its southern continuation instead of 3,000 square miles must have covered

9,000 or 10,000 square miles of ground.

It must now be evident to the reader, that on the east coast of England, and on the adjoining

ground in the interior, there is no want of evidence of a cold episode or of episodes when snow

and glacier-ice largely

[Boulder-Clay. 395]

prevailed in these regions under some form or other. A minority of persons who excel in the art

of doubting will of course dissent for a time, but the proof is too strong to be withstood by

commonplace minds. On the whole, also, it would appear that the complete glacial deposits of the

east of England consist of Lower and Upper Boulder-clays, between which there lie stratified

sands and gravels containing sea-shells, and that these strata were deposited in the sea during a

temporary intermision of the cold of a Glacial Epoch. Shells, sometimes fragmentary arid

sometimes entire, are also found plentifully enough in the Boulder-clays of Holderness and

elsewhere.

In older times the origin of these Boulder-clays was attributed chiefly to icebergs that, laden

with moraine matter, broke from glaciers that descended, during a period of partial

submergence, to the sea, and which, floating south and melting, scattered boulders and stony

debris mixed with fine mud across the bottom of the sea.

But of late there has been

a tendency in some writers to attribute the origin of all, or almost all of

the British Boulder-clays to the direct action of glaciers, and to look upon

them as ground-moraine matter, the moraine profonde of Swiss and French authors,

which is supposed to have a modern parallel in the vast quantity of debris,

believed to underlie and be pushed forward by the mighty ice-sheet that passes

seaward from the great basin of central Greenland, and finds its vents through

unnumbered fords into Baffin's Bay. On these grounds both the Boulder-clays

of the east of England, are looked upon by Mr. Skertchly as having been formed

by the direct action of glaciers, the upper Boulder-clay being the work of

the larger and later ice-sheet,

[396 Glacial Epoch.]

when it so happened that the cold of that region became most intense.

Assuming this theory to be

true, the old glacier must have reached the plateau of Romford that overlooks

the valley of the Thames, and the low country on the coast of Essex, near

Southend. One serious difficulty to its acceptance occurs in the fact, that

on the coast-cliff near Lowestoft there are beds of Boulder-clay which overlie

thick strata of soft false-bedded sands with gravel, and these sands lie

apparently quite conformably and undisturbed beneath the Boulder-clay. If

the latter was the ground-moraine that underlay a heavy glacier pressing

southward, it is hard to understand why the sands show no signs of pressure

and glacial erosion. Neither is it necessary to suppose that glaciers are

always needed for the production of ice-polished surfaces of rock and for

the making of Boulder-clay, for, as shown by Professor H. Youle Hind, the

formation of both on a large scale is now and has been for long in progress

on the north-east coast of Labrador, through the agency of 'Pan ice,' which

'is derived from Bay ice, floes, and coast ice, varying from five to ten

or twelve feet in thickness, all of which are broken up during spring storms.'

This broken ice is pressed on the coast by winds, 'and being pushed by the

unfailing Arctic current, which brings down a constant supply of floe-ice,

the pans rise over all the low-lying parts of the islands, grinding and polishing

exposed shores,' and removing 'with irresistible force every obstacle which

opposes their force . . . and the masses pushed or torn from those surfaces

. . . are urged into the sea and rounded into boulder forms by the rasping

and polishing pans.' Here, too, goes on the process of manufacturing Boulder-clay,

for the deep hollows and

[Ice-marks. 397]

ravines, at present under the sea, the records of former glacial work, are being filled with

clay, sand, unworn and worn rock fragments, producing a counterpart of some varieties of

Boulder-clay.1 I have quoted thus far from Professor Hind's admirable memoir, for it has

sometimes been stated, that all the contorted Boulder-clays and interbedded sand, with shells

entire and broken in England, were pushed bodily upon the land by a vast advancing sheet of

glacier-ice, even to heights of a thousand and twelve hundred feet. As the British Islands during

the Glacial epoch were more than once much in the same state as the north of Labrador, there

can be little doubt that some of the British glacial phenomena were produced by the same causes.

1

See 'Notes on some Geological Features of the North-Eastern

Coast of Labrador,' by Henry Youle Hind, M.A., 'Canadian Naturalist,' vol. viii.