[411]

CHAPTER XXVI.

GLACIAL EPOCH CONTINUED. SUBMERGENCE AND RE-ELEVATION OF LAND, AND FINAL

DISAPPEARANCE OF BRITISH GLACIERS.

IN describing the glacial phenomena, my chief concern in this book is to show the effects

produced by ice on the general scenery of the country, and it is therefore unnecessary that I

should here attempt to go into all the details of glacial and interglacial episodes, and of minor

upheavals and depressions of land, thus seemingly tracing out a chronological series of

geological events as clear and precise as any six or eight stages in the succession of the Oolitic

subformations. It is enough for me at present to deal with a broader view of the subject.

Whether or not, before and during the first growth of the glaciers, the British area, by

upheaval, was united to the Continent, I do not know, but of this I am certain that, probably

during, and certainly after the largest extension of glacier-ice, the land underwent a process of

submersion, and while the great glacier was retiring, the diminishing ice, still descending to

the sea, deposited moraine rubbish there. In Scotland, marine shells in situ. are found at heights

somewhat more than 500 feet above the level of the sea, and if the whole of Britain were then

submerged only to that depth, it must have presented the spectacle of a group of islands. One of

these would consist of the mountainous country north

[412 Submergence.]

of the Caledonian canal, fringed by many small islands on the west. The next would extend from

the canal to the valleys of the Tay and Forth, bordered by many islands on the west and south,

and in both the ground was penetrated by many fords, some of which were longer than our

longest fiord-lochs of the present day. The third large island included most of the country

between the Clyde and Forth, and the Solway and Tyne, while two deeply-indented islands lay

south of that line and the Derbyshire hills north of Ashbourne. On the east of these would lie

fourteen islands, formed of part of the North and East Ridings of Yorkshire, while ninetenths of

Wales would form one large island with many small ones lying to the east, south-east, and

south, including the highlands of Devon and Cornwall.

Such islands, as far as Wales and Cumberland were concerned, I am convinced still maintained

their minor glaciers, which descended to the sea, where their ends broke off as icebergs, which,

floating hither and thither, deposited their stony freights as they melted. We shall, however,

presently see that in some districts there is evidence of the country having sunk much more

than 500 feet.

In many parts of England shell beds associated with glacial material are by no means uncommon,

and it is difficult to believe that in scores of places where they occur, on the coast cliffs between

Berwick and the Humber, they had always been thrust up from the sea by glaciers. The most

plentiful species there, as determined by Mr. Etheridge, are Cardium edule, Cyprina Islandica,

Dentalium entalis, Leda oblonga, and Saxicava rugosa, together with undetermined species of

Venus and Tellina. In Cheshire, near Macclesfield, lying between a lower and an upper Boulder-clay, Professor

[Submergence. 413]

Prestwich found marine shells in sand and gravel at a height of about 1,200 feet. I have visited

the place, and saw the shells in situ; and at Congleton, 600 feet above the sea, I also found seashells.

Similar shell-bearing deposits at a low level are found near the Mersey at Blackpool, and on the

coast north of the Ribble, and I have also observed them in Caernarvonshire in the district of

Lleyn. In the same county similar deposits were found by the late Mr. Joshua Trimmer, about

five miles SE. of Caernarvon, near the summit of Moel Tryfan, at a height of about 1,170 feet

above the level of the sea.. With that locality I have been long acquainted, and in 1876 I

revisited it along with Mr. Etheridge. The section occurs at a slate quarry in the Cambrian

rocks. This, after being long abandoned, has of late years been worked with vigour, and the

result is, that good sections are exposed as the gravel and boulder-clay are gradually cleared

away from the surface. In August 1876 the section was as follows:—

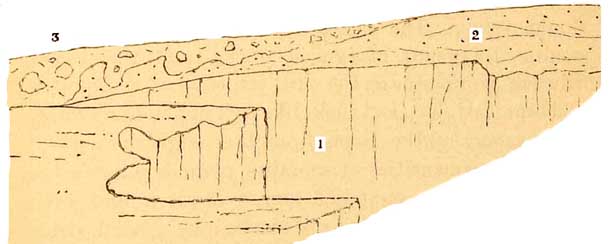

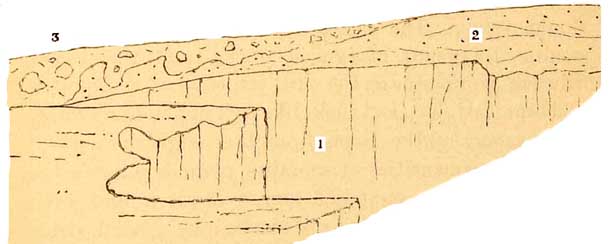

FIG. 84.

1. Cambrian slate. 2. Shell-bearing sands and gravels.

3. Glacier Boulder-clay.

The sands and gravels are all marked by oblique lamination (false bedding) and have a beachlike

[414 Submergence.]

aspect, with sea-shells, broken and entire, of the following species:1

LAMELLIBRANCHIATA.

Cardiurn echinatum, C. edule * and its variety rusticum, Astarte borealis, A. compressa (var.

globosa), A. sulcata, Cyprina Islandica, Teilina Baithica, * Mya? Saxicava rugosa, * mactra

ovalis, * and various fragments.

GASTEROPODA.

Trochus magus, Lacuna vincta,Littorina littorea,* Turritella communis, * Pleurotoma

pyramidalis, P. turricula, Buccinum undatum, Nassa reticulata, Purpura lapillus, * Murex

erinaceus, Trophon antiquum, T. clathratum, T. scalaroides, T.? Dentalium, and various

fragments.

The stones on the ground consist of species of diorite, felspar, porphyry, jasper, chalk-flints,

Silurian slate, &c. The surface of the sands beneath the boulder-beds is very irregular, and has

been much eroded, in my opinion probably by the pressure of a glacier during the deposition of

the moraine matter that forms the overlying Boulder-clay. The latter contains large masses and

smaller fragments of igneous rocks from the Lower Silurian mountains on the east, jasper,

quartzite, purple and blue slate, &c., and looks like part of an old moraine. All the way up the

slope, from the neighbourhood of Llandwrog, quantities of moraine mounds cumber the ground,

and ice-scratched stones abound, and even small water-worn pebbles are marked by glacial

strie. Some of the blocks are very large. In the underlying gravels also stones sometimes occur,

faintly marked by

1

Those marked * were also found by Mr. Etheridge and the author,

[Submergence. 415]

glacial striations, as if the materials, during the progress of submersion, had been derived

from older moraines, and, being water-worn by attrition on the margin of the sea, the original

sharpness of the scratches had been well nigh obliterated.

At various levels on the low

ground between Caernarvon and Criccieth, on the north coast of Cardigan Bay,

there are extensive deposits of sand and gravel, well stratified, and much

resembling those of Moel Tryfaen, but in them I have not yet found sea-shells.

They are overlaid by boulder-beds, and the same is the case with similar

half-consolidated strata on the seacliffs of Anglesea at Lleiniog, and beyond,

between Beaumaris and Penmon near Puffin Island.

Putting all these facts together I see no reason to

get rid of the hypotheses published by me in 1859,1

that, as a slow submersion of the land took place, the diminishing glaciers, still descending to

the level of the sea, deposited their moraine-rubbish there, which matter was often remodelled

by the waves to form sand and gravel. Gradually sinking more and more, and sufficient cold still

continuing, the minor glaciers, descending from groups of icy islands, entered the sea and broke

off in icebergs, which, as they melted, deposited their stony freights on the sands and gravels

that more or less covered the bottom of the sea.

To what depth this progressive submersion may have reached I cannot say, but I think it cannot

have been less than from 1,200 to 1,500 feet. In corroboration of this it is worthy of note that

the Rev. Maxwell Close

has described sea-shells as occurring at the height of

1,300 feet on the Wicklow Hills. The features of the

1 'Old Glaciers of North Wales, and Peaks, Passes, and Glaciers.'

[416 Submergence.]

ground where the circumstances can be best studied are as follows.

On the north-western

flank of the Caernarvonshire mountains, which looks towards the Menai Straits,

there are certain high moorland tracts, the surfaces of which, more or less

strewn with boulders, have very gentle slopes, and when the sections are exposed,

caused by the cutting action of brooks, the subsoil is found to be Boulder-clay,

full of ice-scratched stones. The slopes of Moel Tryfan are surrounded by

such material, which stretches from thence north-east towards the valley

of Llyn Cwellyn or Cwm Seiont, and on the opposite side of that valley, beyond

Bettws Garmon, comes on again in the higher ground. Its continuity is again

interrupted by the valley of Llanberis at Llyn Padarn, on the north-east side

of which, from 800 to 1,200 feet above the sea, the same inclined plains of

drift are continued to Nant-ffrancon, northwest of the great Penrhyn Slate

quarries, while on the north-east side of that valley the same plain stretches

still further north. In one part of these glacial drift deposits, on the

moor of Ffridd Bryn-mawr, I found sea-shells at a height of about 1,000 feet

above the level of the sea, and I was informed by Mr. Trimmer that shells

had also been found in corresponding clays, on corresponding heights, on

the east side of the Ogwen, beyond Bethesda. The shells which I found were

examined by Edward Forbes, but unfortunately they have since disappeared.

Similar deposits in the same region seem to attain a height of at least 1,500

to 1,800 feet, but without insisting on this it is something to be assured

that marine strata-bearing shells attain a height on these Welsh mountains

of 1,000 feet and more.

Further proof of this is to be found in an upper

[Submergence. 417]

detritus which covers much of the lower parts of Scotland and of England, composed of clay,

mixed with stones and great boulders, many of which are scratched, grooved, and striated, in the

manner of which we have experience in the glaciers of Switzerland and Norway. Sands and

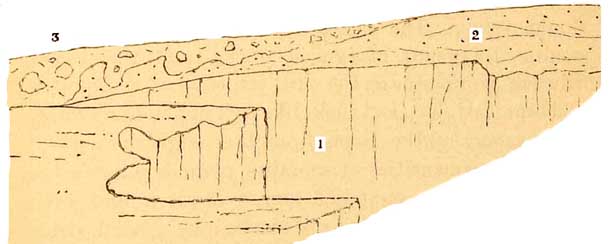

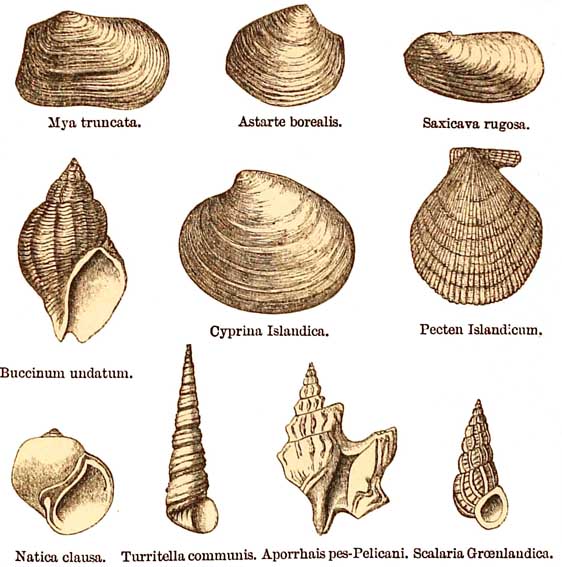

FIG. 85.

Group of Post-Pliocene Fossils, Clyde beds.

gravels, with perfect sea-shells, are interstratified with these boulder-beds, and sometimes

the clays themselves contain unbroken shells, as, for example, in the low ground of Shropshire

between Coalbrook Dale and Wellington. Here and there, even in the heart of the

[418 Submergence.]

moraine-matter of the Till, there are patches of sand and clay interbedded. The main mass,

indeed, is not stratified, because glaciers rarely stratify their moraines, but the waves playing

upon them, as they were deposited in the sea, arranged portions in a stratified manner; and

there occur at intervals in these patches in Scotland

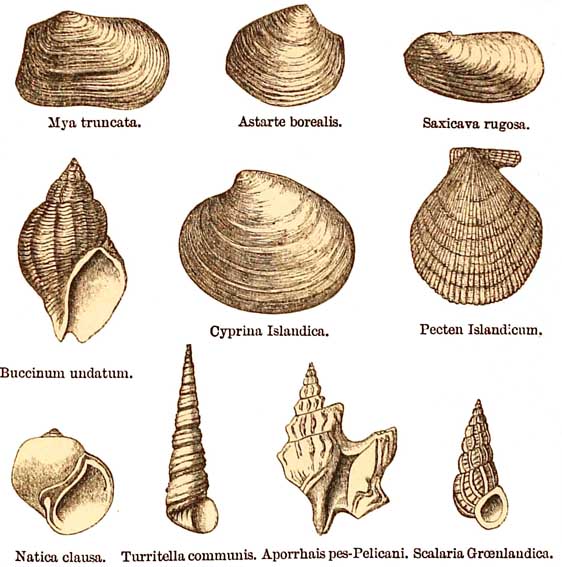

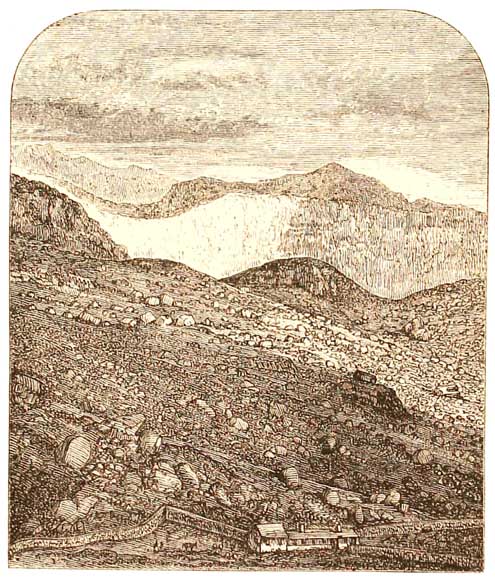

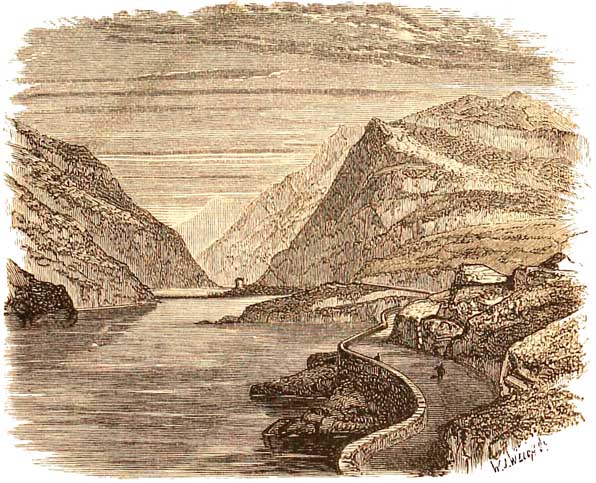

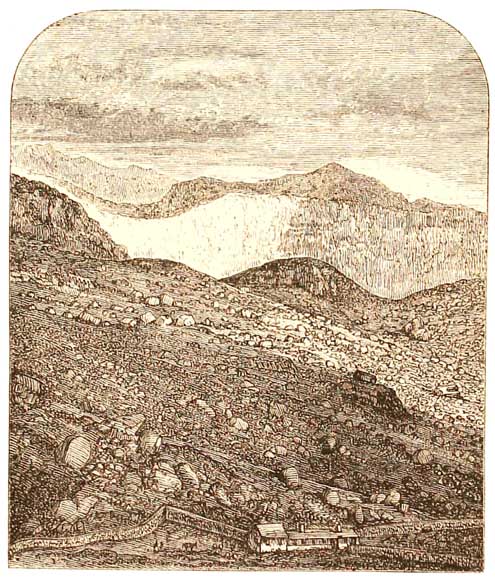

FIG. 86.

Pass of Lanberis.

the remains of sea-shells of species such as now live in the far north.

In the low grounds that border the estuaries and alluvial plains of the Clyde, the Forth, the

Endrick, and elsewhere, up to 12 and 262 feet above the sea, there are well known brick-clays

which sometimes contain erratic boulders and ice-scratched stones. Here

[Glaciers, North Wales. 419]

and there many sea-shells are found in these strata, all of existing species, but the general

assemblage of forms indicates an arctic climate comparable to that of Greenland of the present

day, a circumstance many years ago pointed out by Mr. James Smith of Jordanhill. The evidence

all tends to prove that these strata were deposited during a part of the Glacial epoch, probably

towards its close (fig. 85, p. 417).

After what seems to have been a long period of partial submergence the country gradually rose

again, and the evidence of this I will prove chiefly from what I know of North Wales.

I shall take the Pass of Llanberis

as an example, for there we have all the ordinary proofs of the valley having

been filled with glacier-ice. First, then, during and after the time of the

great icesheet, the country to a great extent sunk below the water, and drift

was deposited, and must more or less have filled many of the deep narrow

valleys of Wales, and which still remains in part in some of the broader

expanses of the country. When the land was rising again, the glaciers gradually

increased in size, although they never reached the immense magnitude which

they attained at the earlier portion of the icy epoch. Still they became

so large, that such a valley as the Pass of Llanberis was a second time occupied

by ice, which, without invading Anglesea, spread itself into the lowlands

beyond, and the result was, that the glacier ploughed out the drift and loose

rubbish that more or less cumbered the valley. Other cases, such as those

of Nant-ffrancon and Aber, could easily be given. By degrees, however, as

we approach nearer our own days, the climate slowly ameliorated, and the

glaciers began to decline, till, becoming less and less, here and there as

they died away, they left

[420 Glaciers.]

their terminal and lateral moraines, still in some cases as well defined as moraines in lands

where glaciers now exist. Beautiful examples of such moraines are seen in the Pass of

Llanberis, between the precipice south of

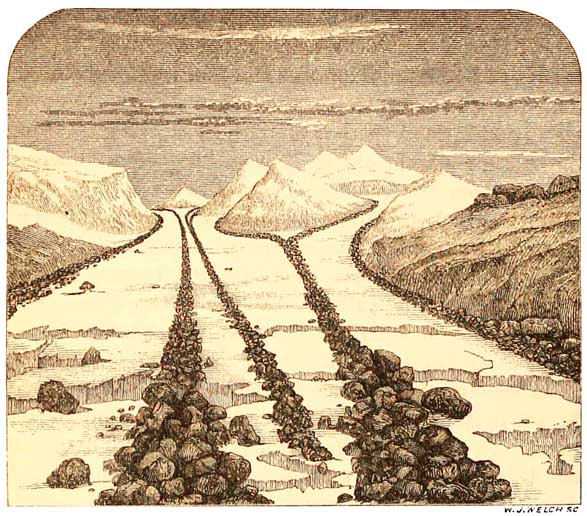

FIG. 87

Moraines and Roches Moutonées between Cwm-glas and Blaen-y-nant, Pass of Llanberis.

the road and the bridge called Pont-y-gromlech. Not far behind the house called Blaen-y-nant,

there is a

large moraine lying on the slope of the hill. It consists of heaps of boulders, clay, and angular

gravel and blocks, identical in genera[l a]spect with many

[North Wales. 421]

Swiss moraines. Some of the

loose stones are scratched, the lines crossing each other confusedly; and

the mass of the moraine is formed of three or four concentric elliptical

mounds, which merge together at their bases, and mark on a small scale the

gradual decrease of the Cwmglas glacier. These circle round the lower side

of a large roche moutonnée, which forms a small hill, as shown in front of

the cliff in the middle of fig. 87.

A little behind this hill,

about half a mile south of Blaen-y-nant, a perfectly symmetrical terminal

moraine, grass-grown, but strewn with travelled blocks, ranges across the

valley between two brooks, almost as regular in form as an artificial earthwork.

It is between 1,200 and 1,300 feet above the sea. Higher up, on the west

side of Cwm-glas, the striæ on the rocks run NNE. below the space where the

glacier, in a cataract of ice, once slid down the cliff that now appears

so grim. Four white threads of water glance on its side, the sole representatives,

in another form, of the jagged ice-fall, that on a smaller scale must have

resembled the icecataract of the glacier of the Rhone. Beyond this cliff,

in one of the innermost recesses of Snowdon, lies an upland valley bounded

on three sides by tall cliffs, in the midst of which lie two small, deep,

clear tarns about 2,200 feet above the sea, each in a perfect basin of rock.

Between these pools and the cliff below, a large quantity of moraine-débris,

derived from Crib-goch, cumbers the ground. The rocks on which it lies are

often perfectly smoothed, rounded, and deeply grooved; and the stri that,

lower down the valley, strike straight towards the Pass, here branch to the

south-west and south-east, following the courses of two minor valleys on either

side of a peaked ridge that descends from Crig-goch to the ground between

the

[422 Glaciers.]

pools. Tiny moraine mounds scattered about, tell of the last remnants of ice ere the shrunken

glaciers finally melted away in the upper recesses of the mountain.

From the summit of Snowdon

three of the old glacier valleys may be seen that radiate from the mountain.

On the east, the magnificent amphitheatre of Cwm-glas and Llyn Llydaw, with

all its striated roches moutonnées, moraine mounds, and numerous perched

blocks; on the south, the deep glen of Cwm-y-llan, with its ice-worn surfaces

of rock on the sides of the hills, in which, just below the peak of Snowdon,

there is a symmetrical moraine about half a mile in length, formed in the

latter days of the glacier, that once flowed down to join the larger ice-stream

that descended through Nant Gwynant and the valley of Llyn-y-ddinas, and

so onward to Traeth-mawr below Beddgelert. Just below the peak lies the broad

precipitous cirque of Cwm-y-clogwyn, in which may be faintly seen the terminal

moraine of a minor glacier, partly circling the pool of Llyn-goch; and, descending

by the path to Lianberis, a vast moraine heap lies immediately north and

west of the deep-set tarn of Llyn-du'r Arddu.

It would be easy for me to give a similar description of the large glacier that filled the valley of

Nant-ifrancon, and flowed onward to where Bangor now stands, where, as a terminal moraine,

it deposited those beautiful wooded mounds that form the park of Penrhyn Castle. Further up the

valley, beyond Ogwen Bank, the river is barred across by striated grits, dotted with erratic

blocks, and high above is the craggy tributary valley of Cwm-graianog. Its whole length is not

over half-a-mile, and at its mouth, above the steep descent to Nant-ffrancon, a small but

beautifully

[North Wales. 423]

symmetrical moraine crosses the valley in a crescent-shaped curve.

Another striking example of the moraines of a retreating glacier may be seen in Llyn Idwal,

first

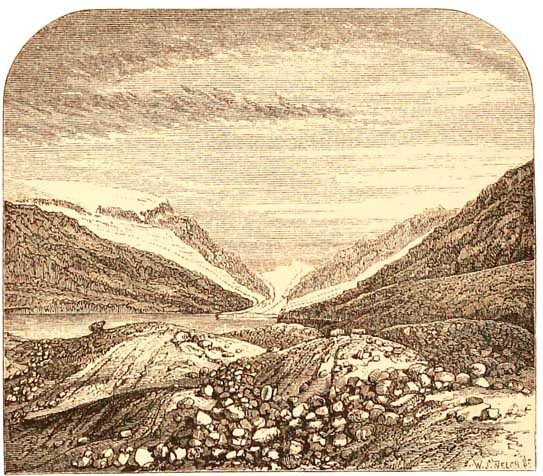

FIG. 88.

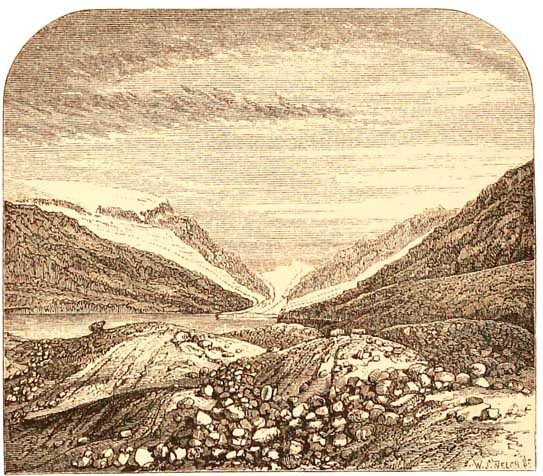

Glacier of the Pass of Llanberis.

described by Mr. Charles Darwin in 1842. Below an amphitheatre of steep hills and cliffs lie

the waters of Llyn Idwal, which are dammed up by ice-worn rocks strewn with moraine. Below

the moraine, down to the Ogwen, the rocks are strikingly moutonnée, the striations gradually

curving round NW. to take the direction of the main valley. On either side of Llyn Idwal lie

several moraines, four in number on the west. They run in

424 Glaciers.

long symmetrical mounds lengthwise in the valley, and were deposited at intervals at the side of

the glacier when it ceased to fill the valley from side to side, and was gradually decreasing in

size. There is also some appearance of an inner terminal moraine where the lake narrows

towards its southern end.

When the ice of these later glaciers of Llanberis and Nant-ffrancon was thickest, in my opinion

it could not have been less than 1,300 feet thick in the former, and from 1,000 to 1,200 feet

in the latter.

In Switzerland there is an offshoot of the glacier of the Aletsch which, at the foot of the

Aeggischhorn, projects from the great glacier a short way into the valley in which the little

lake lies, well known as the Märjelen See. This lake is drained by a small brook, which tumbles

down the rocky ground to pass under the glacier of the valley of Viesch. The right and left sides

of the lake are bounded by mountains, but the side opposite the outfiowing brook is overlooked

by an ice-cliff of the Aletsch glacier, which was about 60 feet in height where highest when I

first visited the spot. The water was then 97 feet deep where deepest, and this I proved by

soundings from the edge of the ice-cliff. Occasionally masses of ice fall from this cliff and break

up into numerous icebergs, some of them large enough to float boulders of moderate size. The

bergs, floating hither and thither, melt by degrees, and boulders and smaller stones are thus

scattered over the bottom of the lake. At intervals, it is said, of about eight years, a crack or

crevasse opens in the ice, and all the water of the lake passes away under the glacier to swell the

river that flows from under its lower end.

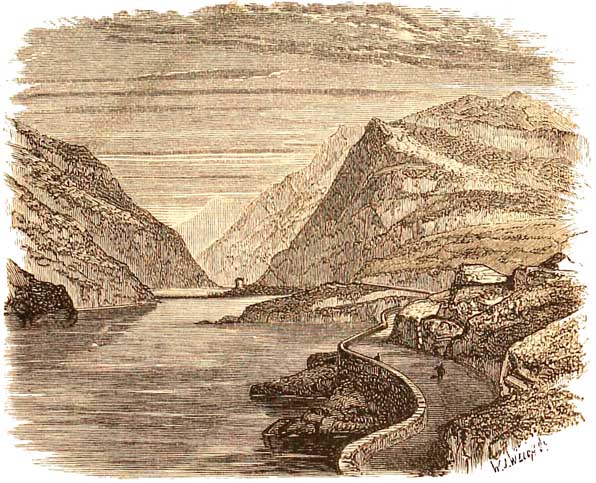

In the valley of Llanberis there are two well known lakes, Llyn Padarn and Llyn Peris, and on a

clear day,

[North Wales. 425]

when the water is still and pure, from a boat one can see boulders here and there lying on the

bottom of the shallower parts of the lakes. In fig. 88 the Pass of Llanberis is represented as it

may have been at some period when from end to end it was comparatively full of ice. In fig. 89 it

is shown as it must have existed

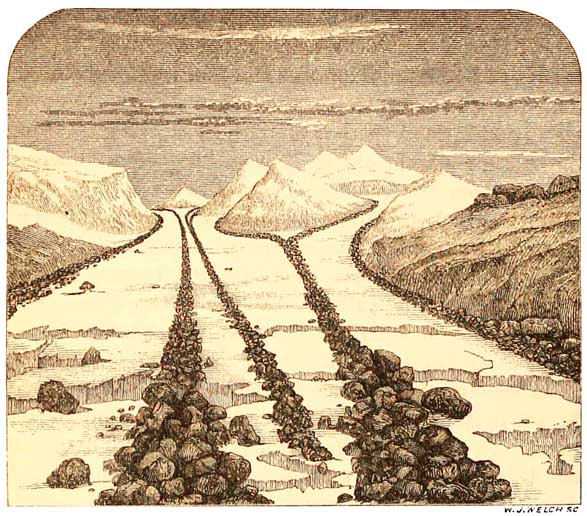

Fm. 89.

An episode in the history of the Glacier of Llanberis.

for a time when the glacier, by amelioration of climate, had retired from all the lower part of

the valley, and debouched into an upper part of what is now Llyn Peris. As it gradually receded,

moraine stones, that fell from its end, got scattered over the bottom of the lake; for in those

days the alluvial flat had no existence which, but for a short river, now divides into two an

older

[426 Glaciers.]

lake of more than five miles in length. In the foreground, are the then unweathered block-strewn roches

moutonnées, on which Dolbadarn castle now stands, which here and there are still marked by

distinct glacial striations. This scattering of boulders on the

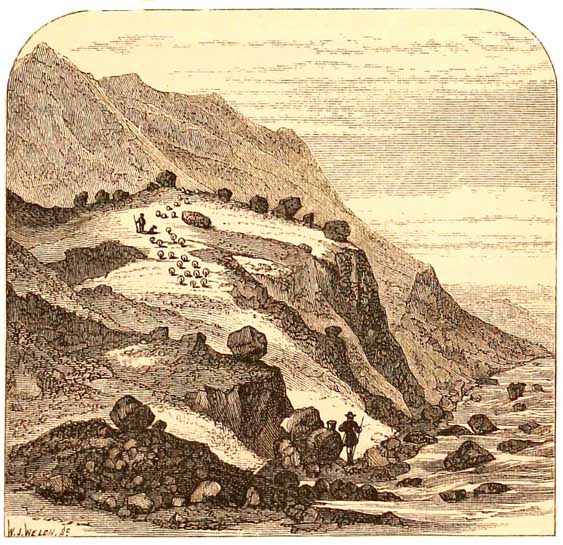

FIG. 90.

Roche Moutonnée, with Blues Perches, Pont-y-gromlech, Pass of Llanberis.

Roche Moutonnée, with Blues Perches, Pont-y-gromlech, Pass of Llanberis.

bottom of the lake is analogous to that which now takes place in the Märjelen See, or which on a

great scale once took place, as the mighty glacier of the Rhone was, from where Geneva now

stands, slowly retreating fifty miles eastward towards Bex. In the shallow water

[North Wales. 427]

near Geneva, boulders shed from the huge glacier may still be seen with their tops above water,

and in the midst of the Delta of the Rhone, between Bex and the mouth of the river, portions of

an old terminal moraine peep through the wide alluvial flats and marshes which began to be

deposited by its waters, at a time when the lake was several miles longer than at present.

The gradual retreat of the glacier of the Pass of

Llanberis is further proved by numerous perched blocks,

which, here and there, isolated or in groups, stand on the surfaces of roches moutonnées, as, for

example, at Pont-y-gromlech, and in many other places, masses of stone that, so to speak,

floated on the surface of the ice, were left perched upon the rounded rocks in a manner

somewhat puzzling to those who are not geologists; for they lie in places to which they clearly

cannot have rolled from the mountains above, because their resting places are separated from it

by a hollow; and, besides, many of them stand in positions so precarious, that if they had rolled

from the mountains, they must, on reaching the points where they lie, have taken a final bound

and fallen into the valley below. But when experienced in the geology of glaciers, the eye detects

the true cause of these phenomena, we have no hesitation in coming to the conclusion that, as the

glaciers declined in size, the errant stones were let down upon the surface of the rocks so

quietly and so softly, that there they will lie until an earthquake shakes them down, or until the

wasting of the rock on which they rest precipitates them to a lower level. Finally, the climate

still ameliorating, the glaciers shrunk farther and farther into the heart of the mountains,

until, at length, here and there, in their very uppermost recesses, we find the remains of

[428 Glaciers.]

tiny moraines, marking the last relics of the ice before it disappeared from the country.

The same kind of evidence of

a period of greatest glaciation, followed by partial submersion, reelevation,

and the gradual retreat of the later glaciers, is plain in almost every valley

in Cumberland, and Mr. Ward confirms this old view of mine, as applied to

Wales, in his late account of 'The Glaciation of the Northern Part

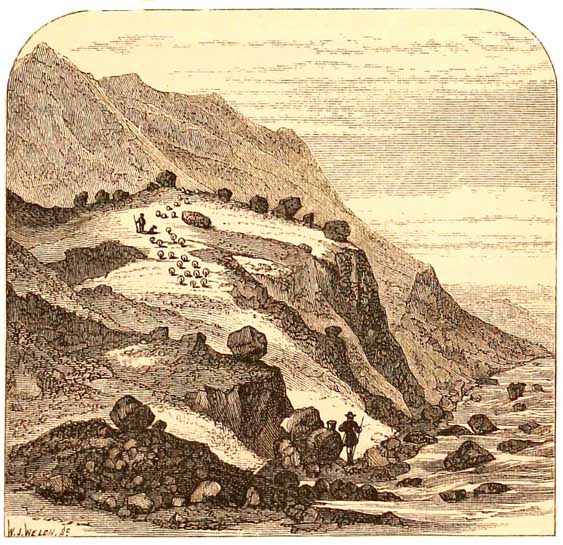

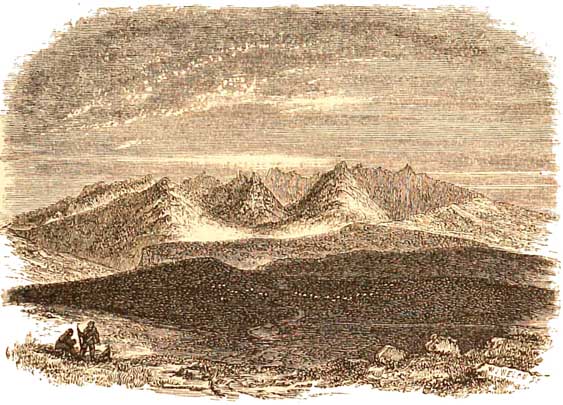

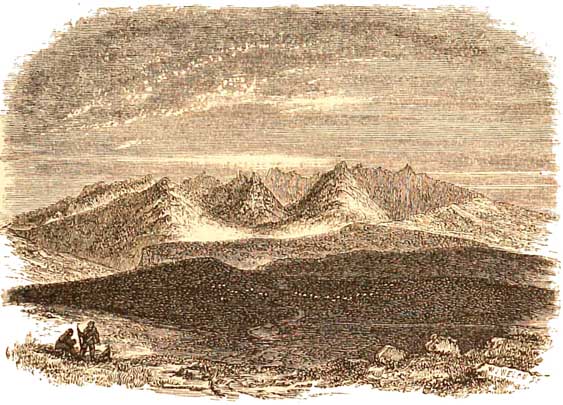

FIG. 91.

Old glacier cirques in Arran, from Lagan Hills.

of the Lake District,' in the 29th volume of the Journal of the Geological Society.

In Scotland also the land underwent partial submersion and re-elevation during the Glacial

epoch, and the gradual retreat of the later glaciers is witnessed in many a valley in the Carrick

and Lammermuir Hills, in the moraines of the cirques of Arran, and through the mainland of the

Highlands, and in Skye in the

[Cirques. 429]

valleys of the Cuchullin Hills. I could give special instances in some of those regions, but they

would add little to the effect of what I have stated, and would needlessly lengthen this book.

Again, when the glaciers were retiring westward, up the dales of Yorkshire and

Northumberland, the ice left, as it retreated, heaps of debris originally forming irregular

mounds, often enclosing cup-shaped hollows; but these, which sometimes still remain in the

more recent smaller moraines, have in the more ancient and larger ones often got filled up by

help of rain washing the fine detritus into them; and the whole has become so smooth that the

original moundiness has, by degrees, been nearly obliterated. In like manner the same has

taken place in the wide valley that crosses England eastward from the bend of the river Lune,

near Lancaster, by Settle to Skipton, including most of the country between Clitheroe in

Lancashire and Skipton, and as far south as Pendle Hill and the other hills that border the

Lancashire Coal-field on the north. And this is what we find:—The great glacier sheets that came

down the valley of the Lune from the Cumbrian mountains and Howgill Fells, and from the high

hills of which Ingleborough and Pennygeut form prominent features, spread across the whole

country to the south, and fairly overflowed the range of Pendle Hill into the region now known

as the Lancashire Coal-field, and far beyond. The result was that the whole of the country

between Clitheroe and Skipton, including the country south of Clapham and Settle, was rounded

and smoothed into a series of great roches moutonnées, partly formed of Carboniferous

Limestone; and as the final glaciers retired, through gradual change of climate, these became

covered with mounds of moraine-matter, now not easy, at first sight,

[430 Glaciers.]

to distinguish from that marine drift which, at equal levels, covers so much of the country

further south.

There is often great difficulty

in distinguishing between these latter moraines and the great masses of moraine-matter

that were formed during that earlier period when the northern icesheet covered

the greater part of Britain, and which undoubtedly were not terminal, but

actually lay under the ice—moraines profondes, as they have been termed by

French and Swiss geologists. Neither is it always easy to distinguish between

this 'Till' and the marine glacial drift when shells are absent, for the

plains of the latter melt into gentle slopes of glacial débris that pass

far up the valleys, and on the hill-sides over many high watersheds.

One reason for this difficulty is that, in certain stages of the history of the period, the larger

sheet or sheets of glacier-ice covered the hills and filled the valleys so thickly and completely

that, pushing out to sea, they even excluded it from parts of valleys that were at a lower level

than the sea itself; and moraine-matter thus got sorted and mingled with other marine deposits.

This partly accounts for the gradual merging of those marine gravelly mounds, called Kames or

Eskers, into Boulder-clay and true moraine heaps full of ice-scratched stones. The Eskers

themselves are often largely charged with water-worn stones originally well ice-scratched.

These glacial scratchings have since been almost entirely worn away by friction, the stones

having been rubbed against each other by moving water. The mere ghosts of the original sharp

scratchings now remain.

The foregoing sketch of the Glacial epoch is of much importance in a geological point of view,

more especially because of the pictures we get of phases of a

[Eskers. 431]

physical geography in these regions, so different from that of to-day, and which judged by any

geological standard is yet so recent. Besides, the events of this period of plentiful snow and ice

gave distinctive characters both to our mountains and much of our lowlands, different, in many

respects, from those of mountain ranges and lowlands where glaciers never were. No one with

an eye educated in glacier work, can fail to recognise the moulding by ice of the outlines of the

Highland and Cumbrian mountains. Their lines are often smooth and flowing curves, and,

excepting here and there, cragginess is not their special characteristic. In North Wales the

mountains are apt to be more craggy, partly because of the variable hardness of the rocks, and

partly because, being further south, that region was not so completely smothered in ice as the

more northern mountains.